SECOND HONORABLE MENTION, FALL 2017

The Ghost Story Supernatural Fiction Award

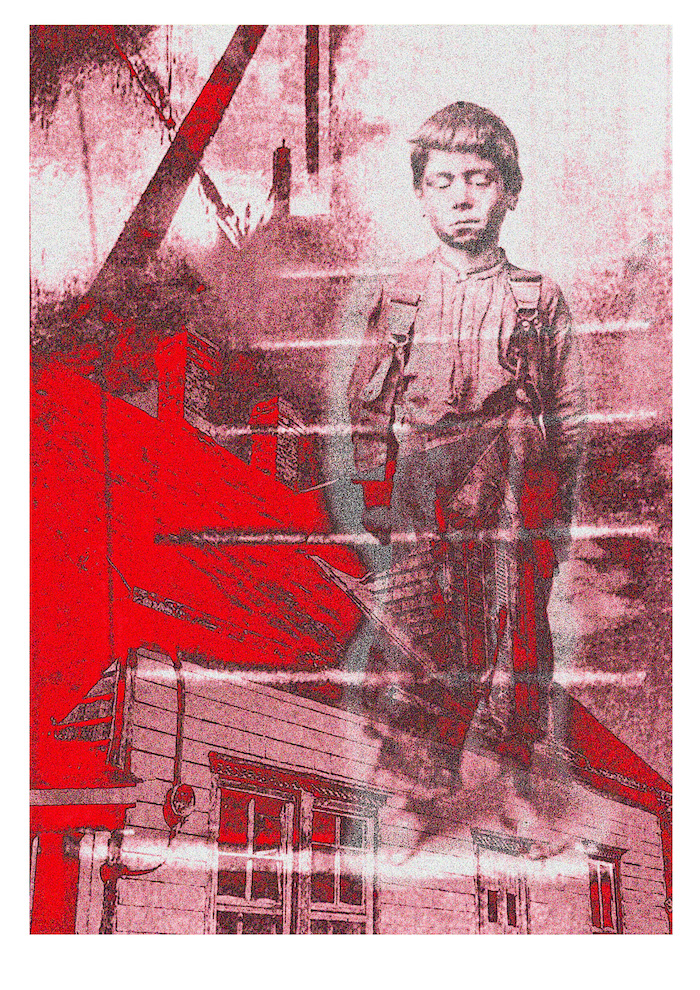

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

BY REBECCA EMANUELSEN

At night, after Mama has already tucked her in and switched off the light, Helena climbs out of bed and makes her way to the chimney stack that runs through her bedroom. She presses her hands to the rough brick and slides them up and down, side to side. This has become her bedtime ritual—feeling for hot spots in the chimney. It’s warm but doesn’t burn her—safe, then. She tiptoes back to bed and draws her blankets tight around her, imagining she is a caterpillar safe in her cocoon. Mama and Papa’s muffled voices drift from down the hall. Helena fights to keep her eyes open, but the sound of her parents talking lulls her to sleep.

She starts awake to a scraping noise in the attic above her bedroom. The room is completely dark, the light from the hallway gone. She wrings her blanket in her hands and sucks in a breath, feeling her heart pound in her chest and hands and ears. She had hoped the noise wouldn’t come tonight.

Another long scrape, heavy furniture against attic floorboards. Helena turns and pushes her face to the wall. She draws her blankets up over her head, tucks the covers behind her back and under her feet. The air beneath the blankets becomes hot, muggy with exhalations.

Upstairs, a steady rhythm begins against the floor. Bmp ump, bmp ump, like the house’s heart is beating in the attic.

After half a minute, it stops.

Helena strains to hear. She relaxes as the silence stretches on, unfurling her legs from the tight ball she’s curled into.

But then a new noise comes: bm-bm-bm-bm-bm, louder, closer with each repetition—something bumping down a set of stairs. Helena pictures the door to the attic across from her room—locked tight, Papa reassured her last time. The noises have come on and off for weeks now, usually staying upstairs but occasionally ending with the door across the hall swinging open. The creaking of its hinges sounds again, but this time Helena hears something else—something rolling right outside her door—and her breath stutters, caught up in her throat. Thunk against her door, and she screams.

Papa arrives quickly, throwing open the door, flipping on the light, grabbing Helena up from her bed. He shushes her, and she clings to him. Over his shoulder, she can see the set of stairs across the hall, the attic door open, and she stares into the darkness, watching for movement.

“You’re getting too heavy for this,” Papa mumbles, patting her hair.

Mama walks into view and huffs. “Not again.” She closes the door leading upstairs. “I thought you said you locked it.”

“I did,” Papa says.

“You clearly didn’t, Christopher.”

“It was locked. The house is old—things shift around.”

“Locks don’t shift.”

The two eye one another as though an argument is on its way, but then Papa sighs. “I’ll look into it in the morning.”

Mama and Papa let Helena sleep in their bed for the night, nestled warm between them. The mattress shifts when Papa gets out of bed in the morning. It’s still dark, so Helena tries to go back to sleep, but Mama’s snoring keeps her awake. She rolls off the edge of the bed, shivering when her feet hit the floor. The fire in the furnace will have died down overnight, as it always does.

She makes it to the top of the staircase in the dark, allowing her memory to guide her. She feels her way down the stairs, light from the kitchen helping guide her way. The door to the basement is open, and Helena can hear clanging below. She calls, “Papa?”

He pokes his head around the corner. “What are you doing up?” he asks.

“Can I come down?” Helena doesn’t often enter the basement—Mama says it’s too dirty because of the coal furnace, which burns hot to the touch.

He twists his mouth this way and that, as he always does when considering something likely to upset Mama—things like sneaking Helena candy in the evening or putting pennies on the railroad tracks by the house so that Helena can collect the shiny pieces of copper after a train has flattened them. Papa gives in to Helena’s request this time, as he often does. “Be careful.” He disappears, and Helena creeps down the stairs.

Just around the corner is the furnace, cast-iron and monstrous. It takes up a quarter of the entire basement. The little door on it is open, a wood fire already burning inside atop a rocky bed of orange-speckled coals.

“The coal is just starting to catch,” Papa says, a shovel in hand. Its metal blade goes shuck-shoo when he plunges it into the enormous pile of coal and lifts it out again. He tosses the coal into the furnace.

“You know how to make coal burn well?” Papa asks.

“You put it on fire,” Helena answers, and Papa laughs.

“There’s a little more to it than that,” he says. He leans down to snatch up kindling from one of the wooden crates where it’s stored. “You can’t add too much coal at once or it’ll smother out.” He tosses twigs and a few dried corncobs in. The cornhusks, still attached to the cobs, ignite and vanish in seconds. After a minute, Papa adds another small shovelful of coal.

Helena has watched the coal being delivered before, heard the rumble and clatter of the rocks traveling down the chute and landing in a pile in the basement, sometimes avalanching until it’s more of a vast black lake than a pile at all. But she hasn’t watched Papa stoke the fire to warm the house in the morning until today. She rakes her eyes over the stove, checking for cracks in its metal surface where embers might jump out.

“How would you like to shovel some coal?” Papa asks. Helena tucks her hands up into the armholes of her nightgown and shakes her head hard, and he laughs again.

A water pipe rattles nearby, and Papa pauses, a guilty look on his face.

“Sounds like your mother’s up,” he says. “You’d best run along.”

Helena washes her face and dresses for school. Her parents are already at the table when she comes downstairs for breakfast. The phone rings just after she’s taken her place, three trills before Mama answers.

Helena uses the side of her fork to slice her egg yolk in two, dragging her toast through the yellow center as it spills across the plate. It’s the way Papa eats his eggs too—mopping up the liquid mess while leaving the whites behind—but he’s already finished his meal and is tamping tobacco down into the end of his pipe.

“Of course you can stay, Francine,” Mama says into the receiver. “When are you coming up?”

Helena draws in a long breath and widens her eyes at Papa. His own expression becomes solemn. His teeth click against his pipe. He glances sidelong at Mama, patting his pockets for a book of matches, but Mama’s facing the wall, scribbling a note on the pad of paper they keep beside the phone.

“Tomorrow? Sure, sure. Christopher can pick you up at the station.”

A flame jumps to life as Papa strikes a match. It fizzles out before he can light his pipe though, so he discards it on his plate.

The receiver lands heavily against its rest when Mama hangs up. Papa takes his pipe out of his mouth when she turns around, as though he’s about to ask a question, but he stays silent when he sees her expression.

“Poor Francine,” she says.

“What’s she coming up for?” Papa asks.

Mama takes her seat at the table, shaking out her napkin and tucking it onto her lap. “Settling some things with the bank.”

“About the house?” Papa asks.

“I imagine. I’m sure she could use a break from our mother too.”

“She won’t be able to talk to anyone at the bank until Monday, you know.”

Mama frowns. “What’s wrong with a weekend visit from my sister?”

A hint of anxiety is evident in the tensing of his jaw, but Papa’s verbal response is conciliatory. “Nothing. It’ll be nice to see her. It’s been months since we were last down to visit.”

Mama eyes Papa a moment longer before she is content enough to carry on. “She’s bringing the baby. She’ll need your room, Helena—you’ll have to sleep with us.”

“Okay,” Helena says, smiling as she crunches her bacon.

Papa closes his lips around the bit of his pipe and lights another match, but it fizzles out too, and he throws it and the entire book of matches onto his plate. “Must be a bad batch,” he says, and sets his pipe on the table.

“That’s been happening a lot,” Mama says. “Maybe it’s time to switch brands.”

Mama cuts her egg up like a little pie, eating it slice by slice. “Anyway, what we talked about earlier—you’ve got time before Helena needs to be at school,” she says, teeth scraping against the tines of her fork.

“Hm?”

Mama offers only a pointed look in return.

Helena chews her last bit of bacon, sensing a conspiracy.

“Right,” Papa says, standing. “Let’s go upstairs, Helena.”

Helena hunkers down in her chair, making herself as small as possible. “Why do we need to go upstairs?”

“Your mother wants me to give you a tour.”

“Why?”

“Up you get, my dear,” Papa says, hoisting Helena from her chair, hands icy beneath her armpits. He sets her down, takes her hand, tugs until she follows. They walk upstairs, turn toward her room—and the attic. Helena digs her heels into the floor.

“Come on, Hel. I don’t want to have to carry you.”

“Why are you doing this to me?”

“I’m not doing anything to you,” Papa says. “You’re hearing branches scraping the roof and wind rattling the shutters, and building monsters from it.”

“I am not!”

“Helena,” Papa says, clasping her shoulders. “You can’t keep waking us up at night. We’ll go upstairs and see that all’s well—and then I’ll give you a ride to school so you don’t have to walk in the cold.”

Grumbling, Helena follows Papa up the narrow attic staircase, dragging her feet over the edge of each step. In the attic, Papa has to stoop, bent over like a giant. A lightbulb hangs from the ceiling, a pull-chain dangling beside it, but Papa simply pushes aside the curtains of the two windows to let light in, illuminating specks of dust in the air. Helena stays close to him, whipping her head around in case something jumps out of a corner. There’s a trunk near the stairs. A few boxes are piled in one corner, pieces of disassembled wooden furniture in another.

“You see?” Papa says. “Just old things.”

“Can I go now?”

“Yes,” Papa says, and Helena is already halfway down the stairs as he calls, “Get your coat on and give your mother a kiss.”

Papa fixes the lock on the door to the attic that evening, tightening screws, allowing Helena to yank on the knob as hard as possible to ensure a fast hold. The night passes in relative silence—a bit of scraping in the attic (branches on the roof, she tells herself) but no locked doors swinging open, no alarming thunks against her bedroom door.

Before school, Helena moves the things she’ll need during Aunt Francine’s visit into Mama and Papa’s room. She piles outfits in her arms, but the pile is precarious, and she loses two pairs of socks as she moves them. She finds one pair in the hall, and the other she spots just under the edge of her bed. When she crouches down to grab them, she is distracted by the other things she sees beneath the bed: a dusty peppermint, a drawing she did of Mama wearing her blue coat. But most intriguing is a ball in the back corner, which Helena crawls underneath the bed to retrieve, ignoring the rest of the items.

Emerging back into the light, she sees that the ball is green, paint chipped to reveal wood underneath. She turns it around in her hands, trying to remember where she’s seen it before.

“Where did you find that?” Mama asks, walking into the room with a dust rag to clean up before Aunt Francine arrives.

“It was under my bed.”

“That’s odd,” Mama says, stepping forward, taking the ball from her. “We don’t own a croquet set.”

Helena leans away when Mama offers it back, and says, “I don’t want it.”

“Maybe it belongs to one of your friends.” Mama drops it into the toy chest. “Ask around at school today.”

Helena doesn’t need to ask around at school though, because now she knows where she’s seen the ball before—it belonged to Wilbur.

Although Wilbur had lived only two towns over with his parents, Aunt Francine and Uncle Edwin, Helena never knew him very well—family get-togethers were irregular. Aunt Francine was Mama’s sister, and though they always ended their visits with promises to call to catch up soon, neither ever followed through.

The last time Helena saw Wilbur was last summer, just after his father, Uncle Edwin, had returned home from shooting Nazis. Aunt Francine threw a party in celebration. In the middle of a game of tag among the children—most of them neighbors, because the family was small—Wilbur had pulled Helena aside.

“Isn’t this dumb?” he said. “Let’s do something else.”

“I don’t know. . . .”

With a slowly spreading smile, Wilbur said, “I could get my croquet set out.” He always seemed to have many more toys than she did.

Helena didn’t quite trust his smile, but she had always wanted to play croquet, imagining the mallets as flamingos, the balls tiny, spiny hedgehogs. “Well, all right,” she said.

The shed was at the very back of the property, its thin side slats splintered with age. Wilbur fiddled with the lock. “You’ll have to help me carry the box,” he said. “It’s heavy.” He hefted the door open, gesturing for Helena to enter.

It was dim inside, and Helena squinted to find a box large enough for a croquet set. But then there was a sudden rush of air, ruffling her skirt. She jumped as the door slammed behind her.

“Too easy!” Wilbur said from outside, laughing.

Helena tightened her hands into fists, annoyed at having been duped.

A minute passed. Wilbur said, “It must be scary in there. Just say, ‘Wilbur is smarter than me,’ and I’ll let you out.”

Helena didn’t say a word. Wilbur had done things like this on other visits—jumping out from behind corners in an attempt to elicit a shriek, dropping worms into her shoes—but after the first time or two, she’d learned to act unaffected. Eventually, he’d get bored.

“C’mon,” Wilbur said. “Say it and I’ll let you out.”

After another minute, he said, “Fine! Stay in there all day then,” and stormed off.

Helena didn’t like being trapped in the dark, but her eyes adjusted, and enough light filtered in between the wooden slats for her to see a few things. She found a dusty stool and took a seat, prepared for a long internment. She tapped her feet and practiced counting to twenty, then noticed a large spider spinning its web over the metal blades of a lawnmower.

Then there was the sound of Uncle Edwin shouting. He soon arrived and flung the door open, and Helena saw Wilbur cradling his ears nearby, his expression pained.

“Thank you,” Helena said to her uncle. He nodded curtly, left the door open, and marched back toward the porch, several hundred feet away, where most of the adults were gathered.

Helena dusted off her bottom, then found a stick on the ground just outside the shed and spun it in the spider’s web, gathering up the spider itself. She took it outside so that it wouldn’t be diced to bits the next time the grass was cut.

After he recovered from having his ears boxed, Wilbur dragged a heavy trunk out of the shed and showed Helena the proper way to arrange the wickets for a game of croquet. They pushed them into the ground, earth giving way to the metal stakes, and Wilbur, only slightly sore over his punishment, demonstrated how to knock a ball with a mallet to send it through a wicket. When Helena’s turn came, she chose the green ball, but was too distracted by pretending to be in Wonderland to do well at all. Afraid of harming her flamingo’s beak or hedgehog’s back, she barely tapped the ball each time her turn came around.

Wilbur was in a better mood after his easy win. They played together the rest of the day, catching toads in the yard and playing tag with the other children.

It was only shortly after that, six months ago, that Mama received the hysterical call from Aunt Francine. Her tinny voice had been so loud that, even from the kitchen table, Helena had deciphered the scrambled message: fire, ash, death. The house had burnt down, and Edwin and Wilbur had gone with it. Only Aunt Francine made it out, along with the baby she carried in her belly. She’d stayed in Helena’s room for a week after the fire, sobbing, despondent. There had been a funeral service, but Helena was dropped at a neighbor’s house beforehand.

A few days later, Aunt Francine went south to stay with Grandma. Before leaving, she’d asked Papa to store a few belongings in the attic. It had been the things untouched by the fire—the shoes and coats that had been in the mudroom, far from where the fire started, and the items from the shed, croquet set included.

Despite the nipping wind, Helena is slow on her walk home from school, stopping to peer in the windows of the small downtown, jealous of a fine pair of gloves at one shop, mouth watering at the sight of rock candy at another. She pulls herself away eventually, drags her feet through the muddy layer of snow coating the road home. Her nose is so cold that it doesn’t feel like it exists at all by the time she arrives. She eases the door open and shut, careful not to let the screen clap.

Chatter drifts from the kitchen—Mama and Aunt Francine. Helena slips off her shoes and leaves them by the door to sneak upstairs. A crib has been set up in her room—she wonders whether it is the same one she slept in as a baby. A suitcase rests by the head of the bed.

The green ball is still in the toy chest, nestled between a scraggly teddy bear and a wooden duck. Some part of her had expected the ball to disappear during the day—back into the attic, maybe.

She wonders what it was like, to burn up inside the house. She thinks of the time she accidently touched Mama’s curling iron, and the time she plucked a hair from her head and held it to the stove burner out of curiosity. It had released a pungent odor as it curled up and turned black.

According to the firemen, it had been a cigarette that killed Wilbur and Uncle Edwin. An untamped cigarette, knocked from ashtray to floor. For a moment, Helena sees flames engulfing her home, setting her bed ablaze as she slumbers.

Because she won’t be able to check it again tonight, she slides her hands against the chimney stack. It does not burn her.

In the kitchen, Mama presses a kiss to Helena’s forehead. “You took your time getting home,” she says.

Aunt Francine sits at the table, a bundle in the crook of one arm. Although her eyes are ringed red from crying, she looks better than last time, hair swept back into a bun, dress tidy. If her nose were more hooked, her hair a bit darker, she’d look quite like Mama.

“Hello,” Helena says to Aunt Francine, hesitating at her mother’s side.

“Hello, dear,” her aunt says. “It’s been a while since you last saw your cousin.” She switches the arm in which she holds her bundle, and Helena sees that it’s baby Edith, her ruddy face peeking out from the blanket.

“She got fat,” Helena says. Mama and Papa had taken her to Grandma’s house to visit Aunt Francine and the baby right after the baby’s birth. Edith had been tiny then, more fragile-looking.

“Babies are supposed to be fat,” Mama says.

“Can I hold her?” Helena asks.

Anxiety flits over Mama’s face, but Aunt Francine is quick to agree.

“Just sit down and use both arms. Make sure you support her head,” she says, setting the swaddled baby into Helena’s arms. Edith’s upper lip curls out, and when Helena leans in to examine her, the baby widens her eyes and sticks her tongue between her lips. Helena returns the gesture.

“She isn’t bald anymore,” Helena says, curling a finger in the baby’s downy hair.

“Mm-hm,” Aunt Francine mumbles, digging through her purse. She pulls out a shiny cigarette case. She already has a cigarette in her mouth halfway through the question, “Mind if I smoke?” and she’s struck a match against its book before Mama can answer. As she raises the lit match, it goes out as if snuffed, a thin trail of smoke dancing from the blackened tip.

“Shoot,” she says.

Another match. The flame flickers, disappears before she’s able to light the cigarette. “Goddamn it.”

“Francine!” Mama says.

“Must be a draft. I’m going to the living room.”

Mama stays in the kitchen and adjusts Helena’s arms around the infant, drawing Helena’s own attention back to the baby. “Don’t repeat what your aunt said.” When another curse word drifts from the living room, Mama adds, “Or that either.”

Helena shakes her head, then watches Edith, who watches her back. She bounces her lightly, pats her on the back. The baby wriggles and lifts a skeptical eyebrow.

“Can I play with the baby?” Helena asks the next morning.

“I don’t see why not.” They’ve had a late breakfast—Mama doesn’t like to get out of bed early on the weekend—and Helena is looking for ways to put off practicing writing her letters for school. Aunt Francine sets Edith on her back on the carpet of the living room and takes a seat on the couch, flipping through a crisp issue of Life.

Helena sits down beside the baby. She rests her hands lightly on Edith’s feet, encircling them, and the baby kicks them around as if riding a bicycle. When Helena dangles a rattle over Edith, shaking it lightly, Edith reaches up and grabs Helena’s pinky, latching on for several minutes. When she gets fussy, Aunt Francine nurses her upstairs, and when she returns afterward, Edith scrunches up her face and spits up on her mother’s blouse.

Papa drives into town after lunch, returning with a new box of matches. Mama turns on the radio and works a crossword in the newspaper, and Aunt Francine runs Edith upstairs for a nap. Helena sits on the floor at the coffee table and works on forming each angle and curve of the alphabet. The radio plays a swing song, quick and catchy, and Helena nods her head to the beat.

When Aunt Francine returns, she sits with Papa on the couch, and they strike one match after another, flames puffing out of existence before they can light his pipe or her cigarette. Finally, Papa strikes three matches at once and manages to press them to his tobacco before they go out. He uses the same technique to light a cigarette for Aunt Francine.

“I don’t know what’s wrong with the air here,” Aunt Francine says, relaxing into her seat as she exhales a lungful of smoke. “Too damp, maybe.”

Helena doesn’t like the smell of Aunt Francine’s cigarettes—too bitter, unlike the homey scent of Papa’s pipe.

“Feels dry to me,” Mama says.

The song on the radio ends, and the announcer’s big, booming voice comes on, but then there is a tremendous whomp from upstairs. The movement in the room is immediate: Helena drops her pencil. Mama throws the newspaper aside, tossing it halfway across the room as though in a fit, and stumbles up out of her chair. Aunt Francine starts and accidentally breaks her cigarette in half between two fingers, and Papa struggles to get up from the deep cushions of the couch. Mama is the first to the stairs, followed closely by the other adults. Helena feels her pulse hammering as the adults rush upstairs, and then she’s running upstairs too because being closer to the noise is better than being all alone far away from it.

The attic door is open, the lock busted. The trunk that had been next to the stairs in the attic is in the hall now, flipped on its side with its clasps broken. A coat and a pair of shoes spill from its mouth. Mama and Papa relax when they see it there.

“Thank God,” Mama says, looking down at the trunk, her hand on her chest. “I thought the crib had collapsed.”

“I can’t believe the baby didn’t wake up from the noise,” Papa says, patting Helena on the head.

“Oh,” Aunt Francine says, and she kneels down. “Oh, oh.” She reaches for a shoe, not much larger than Helena’s own, and turns it over in her hands. Then the sobbing starts. Mama kneels down next to her, and Papa, his pipe still in his mouth, steps over the items and quietly goes up into the attic.

“My baby,” Aunt Francine says.

Mama tries to calm her, but Aunt Francine scrabbles through the items in a hysteria, pulls the trunk further open. The handle of a croquet mallet falls out.

Helena backs away into her bedroom and closes the door behind her as her aunt breaks down. In the crib, Edith is awake but apparently unfazed by the noise. She glances at Helena, opens her toothless mouth, makes a little noise. Helena fits her arm between two of the wooden bars and tickles her cheek. The sound of Aunt Francine’s crying grows distant.

Helena snatches a glance of the green croquet ball from the corner of her eye.

The door opens, and Papa looks around the edge of it. “Oh, just you?”

“I think Mama took Aunt Francine downstairs.”

“Ah.” Papa opens the door more fully and leans against the doorframe. “Well, nothing’s out of sorts upstairs, but something pushed that trunk down. Maybe it’s raccoons you’ve been hearing in the attic.”

“It was Wilbur.”

“Where did you get that idea?” Papa asks.

“The things in that trunk belonged to him.”

“So?”

Helena clasps one of the crib bars tight. “I found a croquet ball under my bed.”

With a wave of his hand, Papa dismisses her evidence.

“And he’s been snuffing out the matches!”

Edith fusses.

“Ghosts aren’t real,” Papa says.

“He’s doing it because he’s angry he burned to death.”

“Don’t ever say anything like that again,” Papa says, not yelling like Mama would, but lowering his voice and letting each word fall like an anvil.

Helena trembles with the injustice of Papa’s response. Edith lets out an unhappy noise.

“Go downstairs,” Papa says. “And don’t speak a word of this.”

“I think you’d better take her to see the doctor,” Mama whispers to Papa in the kitchen. “I already called. He said he can see her at six.”

Aunt Francine has been on the couch since Mama brought her downstairs. She cried for a long time before Mama managed to make her stop. Helena watches Aunt Francine from the bottom of the staircase, perched between kitchen and living room. Her aunt has been staring at the wall, an unlit cigarette dangling from her mouth, for over an hour.

“She seems fine now,” Papa says.

“Fine?” Mama asks. “Do you think you’d be fine if you had just been reminded that you were responsible for the death of your spouse and child?”

Helena, feeling sick to her stomach, throws a worried look toward her parents.

Mama’s cheeks color when she realizes Helena’s overheard, but she doesn’t otherwise respond. Instead, she lowers her voice and says to Papa, “She needs something for her nerves.”

“All right,” Papa says. “I’ll drive her over, but what about Edith?”

“Francine brought Pet milk—it’s here somewhere. I’ll find it.”

Aunt Francine acts like a machine when Mama tells her she’s going to the doctor. She gets up and slides her cigarette back into her case without saying anything. She puts her shoes on and buttons up her coat methodically.

It’s snowing out, light, powdery.

“Be careful driving,” Mama says.

“We’ll be back in a while,” Papa says, giving Mama a kiss. “Take care of your mother and cousin,” he tells Helena, and she nods solemnly.

Edith’s cries are piercing. It’s the first time Helena has heard a baby cry up close, and the volume is impressive.

Mama digs through Aunt Francine’s suitcase. “It’s got to be in here,” she says. “She told me she’d bring a can or two in case we went out.”

“Maybe she’s not hungry,” Helena says. “Maybe she pooped.”

“She hasn’t,” Mama says, dumping the contents of the suitcase out on the bed. A dress, a sweater, hose—nothing but clothing and a comb. “Damn it,” Mama says, then realizes what she’s said and adds, “Don’t repeat that.”

Helena sticks her fingers in her ears. “Can’t you feed her something else?” she asks, hearing her own voice as though underwater.

Mama shakes her head, goes to the crib, and picks the baby up, shushing and cooing.

“Maybe she put it in the pantry,” Helena suggests, unplugging her ears as the baby calms, hiccoughing instead of screeching.

Mama perks up at this. “Go check,” she says.

Helena runs down to the kitchen and opens the pantry but sees nothing out of the ordinary. She throws open the refrigerator, then each cabinet, but returns to her room empty-handed.

“No luck?” Mama asks.

“No.”

The look of disappointment on Mama’s face tugs at Helena. She tries to think up other solutions. “We could go to the store.”

“You know we can’t do that, Helena. Your father took the car.”

“We could walk?”

“Don’t be ridiculous,” Mama says. “It’s a mile and a half away, and it’s snowing. We’re not dragging an infant through that.”

“Oh.”

Mama sets Edith, now quiet, back into the crib. She drums her fingernails lightly on it, thinking.

“Georgia’s son must be a toddler by now, but maybe she’s kept something around,” she says.

“Mrs. Bates?”

Nodding, Mama says, “Come on. Let’s go down before we wake her.”

In the kitchen, Mama calls Mrs. Bates. “You do? Oh, that’s wonderful.”

“Listen, Helena,” she says after she’s hung up, already pulling on her coat. “I’m going to run over to Mrs. Bates’ and pick up some milk. You know where she lives—just down the road—so I’ll only be gone a few minutes. Can you be good while I’m away?”

What if Edith wakes up?”

“She’ll probably stay asleep. If you hear her crying, just shake her rattle or sing to her. Don’t try to take her out of her crib.”

“All right,” Helena says, skeptically drawing out the words.

“Good. Now promise me you won’t answer the door if anyone knocks.”

“I promise.”

Helena goes to the living room after Mama leaves and considers practicing her letters. But the burnt-out matches in the ashtray remind her of her earlier conversation with Papa, when he’d as much as called her a liar.

Helena stands at the bottom of the attic stairs, tightening her hand around the box of matches. She is determined to prove to herself, if not Papa, that Wilbur is in the house. She calls his name and trembles while awaiting an answer.

None comes. Wilbur wasn’t so bad, she tells herself, putting her foot up onto the first step.

After the first step, Helena realizes that she’s growing more frightened by the second, so she grabs her skirt and charges up the stairs before she can think better of it. The attic is musty and pitch black, and she almost hyperventilates as she jumps around, feeling blindly for the light’s pull-chain. When she finally finds the chain, the filament flickers to life, glowing orange-red. Helena turns in a circle, searching wildly for a sign of her cousin, but finds none.

“Wilbur?” she whispers, but nothing happens.

“Wilbur,” she says again, and opens the box in her hand. She grabs the wooden end of a match, hand shaking. “If you’re here, put this match out.” She slides the red tip along the striker, but it doesn’t light at all. She drags it across again, faster, and a flame shoots from the tip and almost instantly goes out. Her breathing accelerates as she stares at the blackened tip. She sets it back inside the box.

Trying not to let her fear show, she picks out three matches at once, struggling to hold them all with the ease with which Papa had held them. She places the tips against the striker, pressing firmly. With a flick, they ignite, but before she has an opportunity to call out to Wilbur, the flames lick her fingers.

She drops the matches automatically, sticking her finger and thumb into her mouth to soothe them. She immediately realizes the danger of having dropped the matches. One is burnt out. Another is still lit, burning against the floor. She leans over and blows at the tiny flame until it disappears. She searches for the third match but doesn’t find it for several minutes—not until the smoke begins to rise from between the loose floorboards.

She drops the box of matches. Her voice lodges in her throat. She sees a flicker of light beneath the floor, thinks that this feeling in her stomach is the feeling of her body turning to ash.

She turns and bolts. Down the stairs, down the hall—then she turns back.

“Edith!” she shouts, as if to rouse the baby to action. Her socks slip against the floor as she reaches her bedroom, but she manages not to fall. She bursts into the room, thinking of how to get Edith out of the tall crib. But when she reaches the crib, she sees that there is no baby inside, no one for her to take out of the house.

“Edith!” she calls.

Not in the crib, not under the crib, not under the bed. Frantic, she flings open her closet and pulls dresses down. She cries as she scrabbles through the toy chest, looking for the baby tucked away somewhere. Upstairs, there is an enormous rushing sound, like dozens of matches being struck at once. The smoke has been getting thicker, but now Helena can hear the fire eating at the house above her. She coughs as she throws Aunt Francine’s clothes off the bed and checks for Edith under the covers.

“Helena!”

The voice is Mama’s, angry.

Helena runs from the room, gasping at the sight of the attic stairs engulfed in flames, choking on the smoke. She hears Mama yelling her name again, but this time the pitch is higher, frightened. Helena reaches the staircase and sees Mama on her way up, still in her coat.

“Come down here!”

“I can’t find Edith,” Helena cries, almost turning back.

Mama says, “She’s on the porch,” and, with a fearful glance toward the end of the hall, she hoists Helena into her arms.

Helena watches her house burn from the neighbor’s window. Smoke billows into the sky, blotting out the stars. When the roof collapses, the fire explodes upward. The fire truck comes, but Mama pulls Helena away from the window before she can see them extinguish the blaze.

“What were you doing?” she says, but only kisses Helena on the forehead, pulls her in close.

Helena looks at Edith, asleep on an armchair, bundled up in one of the neighbor’s shirts. After taking Helena from the burning house, Mama had set her down outside and scooped up Edith from the porch. Mama smacked Helena then, screaming at her for putting the baby outside, for leaving her in the cold.

“It’s the middle of winter,” she yelled. “She could have died.”

Rebecca Emanuelsen’s short stories have appeared in “Shimmer,” “Parcel,” “Sugared Water,” and elsewhere. She lives in Michigan, where she works as a proofreader by day and a copyeditor by night. She is currently at work on a novel.

Rebecca Emanuelsen’s short stories have appeared in “Shimmer,” “Parcel,” “Sugared Water,” and elsewhere. She lives in Michigan, where she works as a proofreader by day and a copyeditor by night. She is currently at work on a novel.