WINNER, Fall 2020

The Ghost Story Supernatural Fiction Award

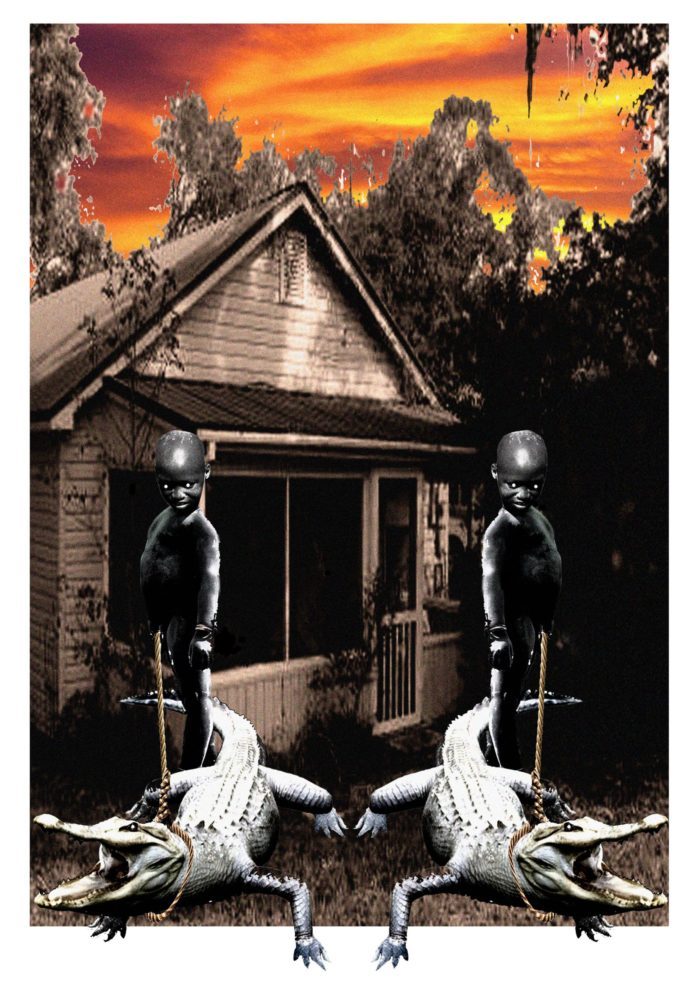

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

BY DOMINIQUE CHRISTINA

Part One: The Old Church Possession

If you’re not from the South, which is to say, if you can’t talk about bottle trees or mason-jar moonshine or spades games that sometimes end in gunshots or the plate of food left for you on the porch or the Piggly Wiggly ritual or how good folks are at remembering and how good they are at forgetting, then you don’t know my people and you don’t know me.

Small towns have a special kind of rhythm. You have to be still enough to find it; still enough to let it find you.

Miss Hall lived in a trailer close by Porter Lake and across the road from the house I was renting. It was a tin-cup-bunioned oddity with random flags in the windows and old snuff cans littering the yard. On my left was a church that had been converted into a rental property. It sat vacant, weeds choking the front lawn and crawling onto the porch. When I moved back to the Florida panhandle for grad school Miss Hall told me the house was empty on account of the oldest girl in a family of four, who got possessed and drove everybody out by making the water rise.

The story goes that this family had been living half a mile or so away when their house burned to the ground. The community rallied around them and determined that they should be allowed to live in the old church that no longer held Sunday services and hadn’t for more than a year—ever since a brand-new brick-and-mortar church, with air conditioning and nicer pews, opened its doors and pulled away all of the parishioners.

The wife the husband and two girls. They moved into the rickety white abandoned church on a Saturday morning. Hauled what they had in an emerald-green flat bed truck. The church was built in such a way that the part of the roof where the steeple had been still jutted out in an awkward way that let you know a cross had been there and probably should have remained. Its absence made the house look more odd than it would have if they had just left the thing alone.

Miss Hall said nothing unusual happened at first. Folks know not to go looking for strangeness. It’s always coming anyhow. But after a while, the neighbors started noticing that the man of the house was always vexed. Sitting outside cussing and carrying on and the mother would be there scratching her head and trying to calm him down. Seemed like run of the mill marital problems at first but when the mother ran out of the house one evening with her husband and the youngest girl right behind her folks knew there was something else happening at the old church.

My boyfriend’s daddy was the sheriff. We called him “Wobbly” on account of him being bow-legged in a way that made it seem like he wobbled when he walked. There was a tick-tock motion about it. Big man with broad shoulders and a thick black mustache that hung past his top lip. I never saw Wobbly out of uniform. I swear to God, even on Sundays that man had on his uniform and you just knew him being sheriff was almost as important to him as being a husband or being a daddy. Hell, maybe more important. Your wife and kids may not always think of you as a hero or a fixer but when there’s a fire or a shooting or the town drunk snatches somebody’s laundry off the clothing line, you are a hero to the people who place the call.

Wobbly got the call. The one that, according to Miss Hall, she knew he’d get.

You can mind your business and still know everybody else’s business. Old folks have been doing it for years but in the South; it’s a science.

And so it goes. Wobbly, being sheriff, got a call from the minister’s wife who had heard something about the church-turned-house from one of the late night cashiers at Walmart who had heard it from her mama who went to Wednesday night bible study with Miss Hall’s son Doker who somehow never missed Bible study while also never missing an opportunity to shoot dope in the back of his mama’s trailer just about every day of the week. Wobbly said the story was that the oldest girl in the house had been witched and was making the house inhospitable for the rest of the family and that folks had decided that Wobbly ought to get over there and help make it right.

Wobbly told them he wasn’t a preacher and that, quiet as it was kept, he didn’t even bother attending church, but they said it didn’t matter how un-churched he was, they just needed the law around in case Jesus didn’t work.

Wobbly got to the house and there were more than a few cars parked in front and across the way and on the lawn. He was annoyed. That’s what he told me. He said it was hot and he had to see about a theft at the bait shop right after but folks insisted he show up and well, Wobbly’s whole identity was about showing up when you called on him. But Wobbly didn’t go in for all that mumbo jumbo supernatural spirit world phooey. He hadn’t gone to college or anything but god dammit he believed in science and provable things and stories about girls getting entranced by the devil or whoever didn’t really jive with his way of thinking about the world.

Didn’t matter though.

He was there. And what he saw interrupted what he had come to believe was possible.

Listen. The devil is busy. I mean, even if you don’t believe in him, the statement is hard to refute. “Devil,” as proper noun for darkness, for evil, for behaviors so ungodly they can’t be readily explained. Some behaviors are so inexplicable they need a demon attached I guess.

So here’s how it went down: Wobbly approached the house, brave warrior, reticent but resolute or whatever and when he gets in the living room he found twelve others congregated therein. Praying and whatnot. Whole room full of “Do Jesus!” and “Come by here Lord” and he was annoyed do you hear me? But then he noticed they were all standing in water. I mean it was up past their ankles. Water in the living room. Eels darting under the coffee table, snapping turtles on the plastic covered couch that had been donated to the family after the fire, blue crab snapping at everybody’s ankles.

It hadn’t rained in a month.

The water levels were low all over Chipley so it didn’t make sense for folk to be standing in muddy water in the living room of an elevated house when there wasn’t any water at all that Wobbly had to trudge through when he entered and like he told me, the house sat up on stilts so the lake would have had to rise by more than ten feet just to get to the front door and it sure enough had not risen. Where was the water coming from? The preacher told Wobbly, the girl was bringing it in. Said she meant to kill everything with it. Said she was in concert with something evil. Said whatever it was that had a hold of the girl intended to drown everybody the way they did folk back in Noah’s time. Preacher told Wobbly, “We need an arc or a mighty faith!” Wobbly told the preacher he didn’t have either. Wobbly was a literalist.

He binge-watched those true crime shows. You know, shows like Cops, and Law and Order: Special Victims Unit and The First 48, the kind of programming that draws a straight line between the crime and the criminal. Standing in that living room, Wobbly wished for a good old-fashioned murder. Hell, even a drunk-and-disorderly would’ve been better.

These folks with their bibles tucked under their arms, shrieking and dodging eels and blue crab in church shoes were saying “the devil” was the culprit here. What was he supposed to do with that?

The minister was waiting for Wobbly to do something. Wobbly’s face was impersonal and flat. He was hot, the living room crowded, and the water rising if you can believe that. He could feel the water sloshing between his toes having climbed over his work boots and in this moment all he wanted was an urgent call so he had a reason to get the hell out of there.

The preacher said, “That gal is bringing the water in. She’s the one doing it. There’s a snake in bed with her.”

Right around the time Wobbly was getting ready to tell the church folks he was an actual police officer who didn’t have the proficiency for this mess, the whole house got cold. I’m talking ’bout cold. Wobbly said it was almost unbearable. One minute he was sweating and the next he could see his breath in front of him, his hands shaking and stiffening from the intense cold. Wobbly told me he had been in Florida all his life and had never felt that before. It was the kind of sudden frigidity that made his bones ring. Oh Lord, this ain’t regular. That’s what Wobbly was thinking. When something unexplainable happens you . . . can’t explain it. It just sits heavy in the room and in the body and you have to deal with it because well, it’s there whether you have a name for it or not.

Wobbly stood with his head down for a few ticks too long looking for an explanation of any kind and when he couldn’t come up with one he walked slowly to the back bedroom where the girl was. Preacher said she had a snake in bed with her. Just before Wobbly opened that door he thought the man was speaking in metaphors the way preachers do but when he pushed that door open—and he had to really push on account of the water making everything heavy—a large snake, marbled scales, three eyes, one green, one yellow, one white, coiled around the footboard, opened its mouth and when it did two things happened. The eels, the crabs, and the snapping turtles all cluttered in the doorway slapping Wobbly’s ankles, and the girl in the bed started to hitch and convulse like she was trying to cough something up. Her face twisted in agony, when she opened her mouth seawater poured out.

The girl’s father was in one corner of the room, his wife in the other. The daddy looked war-whipped, the mother stricken. Both started weeping when the girl brought the flood. Wobbly could see the girl’s eyes rolling in her head like marbles. Breathing shallow, short bursts of pale white clouds coming from each exhalation because the daggom room was so cold. The daddy was wrapped in a blanket. The mama was swaddled under a heavy quilt, but the girl was sweating.

Wobbly walked over to the mother and leaned down. “What ya’ll call her?’

“Juju.”

“She talkin’ to anybody?”

“Naw. She can’t make words.”

“Doc look at her yet?”

“Yeah. He ran outta here ’bout an hour ago. He say ain’t no pill for this.”

At that moment the girl started grimacing and groaning as though she was being choked. Wobbly said soon as she started up with that the room got hot. Not the heat to which he was accustomed. No. Scorching hot. Unreasonably hot. Unseasonably hot. The girl’s father snatched a handkerchief from his front pocket, stood up abruptly, walked over to his wife and guided her out of the room. Wobbly was kind of glad he did that. He didn’t want to be in that room but he also didn’t need the extra burden of having to appear like he knew what he was doing so it was good he had the room to himself.

Wobbly looked around and noticed that the bedroom had once been the preacher’s office. He looked up at the tiled ceiling and noticed holes throughout. He saw the embroidered cross still tacked up on the wall next to the window facing the front yard which had more than a few stragglers on it by then. Folk can’t help but want to know what is sometimes unknowable.

Wobbly wanted to be outside with them. His mind was running all over. He almost didn’t notice how his uniform was wringing with sweat. But the heat wasn’t making him as uncomfortable as the girl was.

His discomfort was fructifying though because when Wobbly was uncomfortable he did something about it and what he did in that instance was to say the girl’s name.

“Juju. Can you hear me gal? What’s got a hold of you?”

And Juju responded by levitating. That’s what Wobbly told me and I believe him. Said she rose up off that bed with her arms stuck out and her head back. Wobbly said when she lifted off that bed, the two braids in her head unwound and kelp pushed out of her scalp dripping water on the pale pink bedspread she hovered above.

That’s when Wobbly started praying. Said he hadn’t done that since his mama died so we are going back years and years but there he was. Taking his firearm off his hip and unsnapping his holster from his waist, Wobbly got down on his knees and prayed. He didn’t talk to God outright. Instead he spoke to whomever or whatever had a hold of that girl in such a way that she was somehow floating.

The preacher opened the bedroom door and saw Wobbly on his knees. He saw the girl hovering above the bed. He turned his head and stared for a moment at her parents beside him in the hallway, weeping and howling into the blankets they clutched to their chests. Then, quiet as church, he motioned for all the others to come near. The preacher took one step toward Wobbly and placed a hand on his shoulder. The woman behind the preacher placed her hand on him. The person behind her put their hand on her shoulder and so on, forming a chain.

“I ain’t sure what you are.” Wobbly said. “I ain’t even sure what you came for. But you let that gal go and I’ll see to it they leave tonight and won’t nobody else disturb your rest, you hear me? Whatever you are. Whoever . . . I’ll get everybody out of here right now if you turn that girl loose and I’ll see to it that this place stays empty, hear?”

And the folks behind Wobbly were moaning and saying “Yes God” and “Fix it Jesus.” And Wobbly said, “Juju you get on back in your body hear? Your mama and daddy waitin’ on you.”

Wobbly said nothing moved. Girl, still levitating. Devil, still busy. Room, still hot. Water, still rising. Eels, turtles, and crabs still clustered in the doorway.

Wobbly felt something hitch. Not in the bedroom. In him. In a low place. The moaning place. Said God or something like it showed up. Gave him a righteous knowing. Said he knew all he had to do was get off his knees and touch that girl. Said he knew once he did she’d come on down. Be herself again. Almost undone but not quite. But God, you know? But God.

So Wobbly got up. Without want, lord have mercy, maybe for the first time. No deep need. No holes in his chest. Creation-heavy and hymn, you know? A libretto for the lost son. Faithful and ready. Yeah that.

Wobbly said he touched that girl and she immediately fell hard on the bed gasping and looking around wild-eyed and confused, panting ugly but woke and un-ridden. The muddy water receded taking the creatures with it. The house seemed to swell then settle, almost a sigh but not quite.

The people gasped and cried holy. Wobbly let them have it. He told the father he would be back in a couple hours to help them get loaded up and out of there. Said he could round up some good folks who would let ’em stay a while until things moved around.

He walked outside and felt the stretch of his bones, really felt them. He looked back at the house and it seemed too small, too slight to have hosted all that ruckus. He looked over toward the lake and saw the shore pocked with dead fish sizzling in the heat. Bluegill, flounder, sunfish, crappie, carp, catfish, pickerel, gar, all steaming on the shoreline, yellow smoke rising from their charred bodies. Wobbly said he never went fishing after that. Never got in the water again. Never stuck so much as a toe in that water. Never rode past that house after that day.

I asked him what he made of the whole thing.

“When a man climbs to his full height that’s prayer,” he said. “But when he climbs above it, that’s God. Evil ain’t figured out how to mess with that.”

I’m just tellin’ you what he told me.

Part Two: Miss Hall’s Brother Boogie

Old ladies don’t have any business being surprised when folks start dying. Death has a disquieting familiarity about it. Its persistence well documented. Its inevitability, unquestioned.

Still.

Miss Hall wasn’t ready to bury Boogie. It’s not on account of him being healthy or too young to die or anything as obvious as that. In fact Boogie was drinking himself to death and to be honest most folk were surprised he hadn’t been laid low by the bottle way before he fell out but Boogie didn’t die from the bottle or a gunshot wound on account of messing with some gangster’s woman (which he was prone to do). No. Boogie died cuz he couldn’t get the ghosts off him and that’s just a fact.

Vietnam orphaned everybody.

Young men came back (if they came back) amputated and hollowed out. Memories of landmines and kids with machine guns and coconut palms split clean down the middle and the boys you buried and the ones you couldn’t and the noise man, and the hurt and the longing and the numbness and the rage and the primal inertia. All of it unfastens a man.

Boogie had the reading proficiency of a third grader but he could knock a man down without much effort and he didn’t know enough to be afraid of anybody so he stood tall like that and folks respected him for it and he liked guns and shot with uncanny precision no matter what was going on around him. No matter the noise or the men falling or screaming, he hit his target damn near every time so his platoon let him lead and he liked it cuz that’s what men do and Boogie was a man. He had been since he was a boy and couldn’t nobody tell it differently.

He didn’t think twice about enlisting. He was changing tires at the gas station when an army recruiter came by for a wash and wax and before Boogie knew it he was pledging his allegiance and swearing to protect and defend and shit got real, fast. His mama barely looked up from her TV Guide when Boogie told her he joined up and would be shipping out in a few days.

Hoo-ah!

Miss Hall said when Boogie got back “he didn’t work right.” He showed up on her porch with his duffle between his legs asking for cornbread. She hadn’t seen him since he got on a Greyhound headed to a place she had never heard of or considered before her baby brother said he was going there as an army man in order to buy a house when he got back home.

He didn’t knock on the door or walk right in which he could have done. Instead he sat on her porch until she came out and when she did he casually asked if she wouldn’t mind making him some cornbread. He had been gone more than a year and it didn’t occur to her that she could have written him a letter to get him through the days and nights in the jungle until he was back sitting on her porch with a brokenness about him she hadn’t seen before and an emptiness she didn’t know what to do with.

So she did what she knew how to do. She made him cornbread and left him to his sadness. The men in her family never spoke until they were ready to anyway so she made the cornbread he wanted and took his duffle from him saying she would wash what was in it. She offered him a pallet on the floor but he said he didn’t need it. Told her he was renting the house across the road.

Same house I would move into later when I was working on my master’s degrees at Florida State University.

First few nights in Saigon, Boogie didn’t go through much. Getting there was more painful than finally being there. But by week six, Boogie was disemboweling members of the Viet Cong and lobbing grenades into huts before stepping past the bodies of kids cut in half by the blast to light a cigarette while old women shuffled meekly past him to lay the bodies out on bamboo mats used for drying rice.

Five months in and Boogie couldn’t remember any of his cousins’ names. Couldn’t remember his sister’s favorite ice cream or how old her little boy was. He couldn’t remember a thing the preacher ever said even though his mama made him go to church every Sunday and speaking of his mama, Boogie thought that if she cared about him even a little bit she would have never let him enlist at all.

By the time he had been there a year what was left wasn’t Boogie. He shot a twelve-year-old boy at point blank range in the Quang Ngai province just to see who would run and who would stay put when the bullet exited the boy’s skull and that’s when he knew he wasn’t gonna make it home. He might not get killed but he had died sure enough.

Boogie had done other things too. Things he couldn’t even get right with God over. He had done things to women over there that didn’t make sense and when he thought back on it, it was like he was watching a movie. Like it was somebody else doing all that ugly.

It was getting harder and harder for him to remember faces. Everything was starting to boil down to small snatches of insignificant items.

One girl had on a red shirt.

One of ’em had a scar on her thigh.

One girl had two long ponytails.

That one didn’t have any hair between her legs. . . .

He had held each one under the water when he was done with them, watching dispassionately as they kicked and sputtered and tried to stay. He didn’t know why he brought them to the water. He didn’t know why he did what he did except that he could and nobody was gonna mind it much since it was war but he knew there would have to be a reckoning for the ugly he had done. He knew that much.

And he knew he didn’t deserve forgiveness so he didn’t bother asking God for it. Some folks don’t get redemption. Some folks give up God and get the ghosts instead. Boogie was one.

And so it happened that the very first night Boogie slept in the small ranch style three bedroom house across from his sister’s double-wide trailer, the ghosts came to visit . . . and they never left.

Miss Hall said every night for more than a month Boogie woke up the whole block with his hollering. She said nobody caught any fish that year. She said the wasps tore everybody up. She said it was like something out of the Old Testament. She said pestilence and she said plague and she said Boogie was responsible on account of him bringing back all those ghosts from Vietnam. Too many, she said, for the sea to be anything other than angry.

Boogie started drinking. Every day. He didn’t waste any time looking for religion or redemption. Not everybody is entitled to get on the other side of their sins. Some folks, Boogie reckoned, were meant to be tragic. He was just one of many. He knew that math well. He had seen tragedy do you hear me tragedy and somehow he was lifted out of those damned jungles and set back in the Florida panhandle in spite of everything he had done and everything he had seen and everything that had been done to him and nothing had changed with any of his people. They still sat on porches that leaned from humidity, chewing tobacco, drinking whiskey out of mason jars and fishing for crappie and catfish, frying whatever they pulled out of the water, and swatted flies and set crawdad traps and didn’t ask him anything about his heart or what it was like over there or why he couldn’t go fishing anymore or why he hollered every night. Naw. Nobody asked Boogie anything. He was a bruise and life was already hard down there, so who in the hell had time to wonder after a grown man who kept running into his sins? Nobody. Nobody had time for that.

It took the ghosts a year to convince Boogie that he deserved to die for what he had done. And a year is a long time. Boogie was proud of how he held out. He knew he wouldn’t win. It wasn’t about trying to prove something different. It was about giving all those dead folks the dance they wanted before he, one night, sat on the edge of his bed and ceremonially put on his service uniform, polished his boots, holstered his revolver, and walked out his back door, down the road, and directly into the same sinkhole that drowned an eighteen-year-old girl in the spring of 1890. Folk ’round here say the ghost of that girl rises out of that sinkhole on foggy nights gnashing her teeth and shrieking one thing: Un-spell me. Un-spell me.

Local fishermen had tried many times to drain the sinkhole but the water always rose faster than they could pump it out. They had to use grappler hooks to retrieve Boogie’s body. It took hours on account of the hole being more than thirty feet deep and hungry and when they finally did pull Boogie out of that sinkhole, he came up covered in scales, three snakes oozing out of his mouth, one green, one yellow, one white. Nobody knew what to make of that and nobody wanted to ask.

Again. This is the South. We know something about being impossible.

Miss Hall buried her little brother on a Saturday afternoon and then sat on her porch facing the house Boogie lived in chewing tobacco, not crying. She couldn’t figure how to do it. She knew she was sad all over. She knew she should have touched his hand or pulled him inside to look him in his face and tell him to shake the devil off but she didn’t. Some acts of kindness can’t be accommodated on account of how they interrupt what a woman needs to do to muscle through her own God-walloped life.

But see now she’s thinking about all the moments she didn’t offer to her brother and he went and walked into the water on Monday and she figured on him leaving even though she wasn’t ready for it and didn’t get in the way of it she still felt a way about it and how the preacher said things about Boogie that just weren’t true because he didn’t know Boogie and the people who did know Boogie couldn’t make themselves participate in some plotted-out death ritual what with so many others that drop in without warning and change the weather forever.

So she sat there. Ordinary plain brown-bag old woman with diabetes and swollen ankles, she just sat there. Looking at the house her brother lived in when he decided to let the water take him. She had half a mind to burn it down but they didn’t burn the old church down next door even after that gal went and got herself possessed so why would she burn down a perfectly good rental house? She wouldn’t. Besides, the house wasn’t the problem. Boogie was the problem. He got out of Vietnam but he brought some haints with him . . . possessed in his own right but it wasn’t no devil that did it and sometimes when a man is scalpeled against his own sins like that his private regrets detonate publicly. Boogie’s did anyhow.

Miss Hall sat on that porch. Sun going down, orange-husked sun sinking behind the trees and right then Miss Hall saw two starch white alligators coming up the road, each led on a leash by two little black boys with no clothes on. Eyes glowing white like the gators. I’m talking about babies. Miss Hall said they were no more than three years old. Two boys not old enough to be in school, not old enough to be on the road without an adult with them, walking those damn gators like pets.

Ethereal. Impossible.

She was looking hard. It didn’t make sense. White gators? How? What water they belong to? White gators? Not a spot on ’em? They looked like porcelain figurines. Didn’t make sense. And then she noticed that the gators were synchronized. When one turned its head the other one did too. Same time. Same direction. Didn’t make sense. They stopped directly in front of the house Boogie died in. Just stopped and stared. Finally they turned toward her.

Miss Hall said that was Boogie’s ghosts coming to make sure it was finished. “But then again,” she cogitated, “Might have been Boogie himself you know? Boogie coming by with my daddy and that was them telling me not to keep my head too low.” Miss Hall nodded her head and stood up abruptly. “I like to think it was my baby brother and my daddy coming by here to let me know they’re together on the other side. This, the South,” she continued. “We always got more evidence of ghosts than God ’round here anyway. You hungry? I got some greens from last night. . . .”

I said yes to the greens even though I wasn’t hungry at all. I know a Passover moment when I’m in one. You eat when they pass the plate around. You listen to the parables and draw from them what lessons you can.

All I know is, Boogie brought some ghosts back with him on account of who he was when he was in Vietnam and they wore him out. Like ghosts do.

I’m just telling you like she told me.

Part Three: Water Wanna Keep You

Anybody who lived ’round Chipley, Florida before before knows this story and they’ll tell it to you if you have a mind to ask but I’ll tell it to you now and you can fact check it like they say on the news cuz I ain’t makin’ nothin’ up or putting nothin’ on it. I’m just gon’ tell it straight cuz there’s another hurricane coming and it’s gon’ take more than a few folk with it.

Let me back up.

White folks got one way. But when you try dominion over anything meant to be free you gotta tangle with the thing that gave ’em that freedom and since God ain’t to be trifled with, when karma comes, it comes in mean. My nanny is from Jamaica. She brought blue bottles, a handkerchief full of snuff, three cornhusk dolls made to look like the babies she couldn’t keep, and a long piece of wood wrapped in a white cloth that she said her granny tore out from the ship she laid in to get to the Americas during the long siege of the slave trade.

My nanny says the Atlantic got a long memory. She says it forgets nothing. She says it’s the world’s biggest and deepest grave. She says the Pacific ain’t got the same sorrow. My grandfather took her to California for their anniversary one year and convinced her to get in the water. She said when she got in she expected the same snatch and snare she felt so many times back home in the Atlantic but it didn’t come. She said it was “downright soft.” Low purr. Fish flapping plainly . . . simply. No rumble. No red. Just blue water and folk riding it joyfully.

They used to feed black babies to the alligators in Chipley. That’s just a fact. Black babies were used as gator bait. It got to be a popular option for poachers who faced no consequences for sacrificing babies to the swamps and the creatures in it. Gator bait. That’s what they called black children. Gator bait.

Nanny said that’s how ghosts get born. You take a hallowed thing, a sacred thing, and feed it to the deep, you gon’ have to answer for it one way or another. My nanny said the slave ships kept sharks swimming behind them on account of all the bodies that got tossed overboard. You know, the ones who got sick, the ones who couldn’t stomach the ride? They all went overboard. Sometimes they went if the ship’s captain didn’t have enough rations to feed everybody. Sometimes they went willingly. Jumped over. My nanny said the Igbo did that. She said they looked ’round and didn’t like what they saw so they locked arms and walked into the water. Some folk say they jumped. Some say they walked on top of the water like Christ . . . all the way back to Africa. But nanny says they died. Willingly died. She says they let the water keep ’em. Added their bones to all the other bodies littering the bottom of the Atlantic. My nanny said that’s why Mami Wata started snatching swimmers and taking ‘em down into the deep with her.

I was six when I saw her for the first time. When she came up for me.

“Yeye! Get the buckets we goin for crawdads!” My nanny shouted. (My family calls me Yeye. You cannot. My name is Yemaya. Call me that or don’t call me.) Anyway, going out to fish for crawdads is my and Nanny’s ritual. My little sister hated it so we don’t bother asking her anymore. She doesn’t like eating ’em. She doesn’t like cleaning ’em. She doesn’t like catching ’em and she doesn’t like sitting out on the banks in the sun waiting for the buckets to get full. Nanny stopped asking her to come and it became something sacred between her and me. I liked it that way. Nanny and I have a shine. She knows my stories and I know hers. You can get a lot of medicine from a story. But you can’t share ’em with everybody. Some folk are sick in a way a story can’t fix.

Nanny was the first person I smiled at they say. My mama never could figure out how to manage me right. Probably because I am my own but I am more too. My mama didn’t know what to do with the “more” part but Nanny always did on account of her being “more.” Nanny’s been here many times. She’s old in an uncountable way. My mama says Nanny is old as Methuselah and that means old.

So anyway I’m tying my hair up and hustling to the kitchen so I can eat biscuits and gravy before heading out with Nanny who had already eaten two pieces of toast with peach preserves and black coffee. Only a half a cup though, any more than that and she acts up.

“Today came in strong Yeye you feel it?” Nanny asked me when I plodded into the kitchen still fussing with my hair, which never does what I want it to do so I usually end up tying it up in a scarf.

“I felt something Nanny yeah but I can’t say what it is,” I said, snatching a biscuit from the pan and slathering it in red gravy.

“Something comin’ on I know that much,” Nanny continued. “We gon’ run into something I reckon. . . .”

Nanny is always right about ghosts. Always right about spirits. Always dialed in to something old and un-language-able. So I believed her.

That day we set our traps in Lake Powell and then we walked over the dunes to the Gulf. We laid a blanket down, pulled out soda crackers and Coca-Cola in case the day went long, and waited.

There were signs posted all over the beach advising caution.

Folks keep drowning in Chipley, see.

Babies drowning in shallow puddles, little kids falling into wells, a high school graduate dying in a vortex of water in the Atlantic, a group of five young men on spring break being pulled under the water, a young lady walking into the Ochlocknee River near Tallahassee in what folk called a trance . . . so many of them. More than a few were good swimmers. Still. Pulled under. Inexplicably.

It always goes the same way. Water has a way of claiming things here. Nanny says the water is ghosted. She says conjure. She says Mami Wata. She says the water wants reclamation. She says the debt is high and has to be paid.

All I can do is tell you what I saw.

Nanny was on her knees scratching veves in the sand, unblinking. I walked to the water’s edge and looked out. The green water was vibrating. Not the ground beneath it. The water itself. Yellow light coming up from it. Looked like a beam. Looked like a shriek. I saw a woman walk out of the water. She had a snake in her hands, tail flicking between her breasts, yellow eyes, her and the snake both. She was looking right at me. The hunger in it pulled me under. I felt myself going down and down.

I wanted to go. I needed to go. My need was a two-headed hydra, hungry and I meant to feed it. She was the biggest pronoun. She was the deepest love. She was the oldest ancestor. She was familiar.

She swam in to me, or I swam out to her, I still don’t know. Nanny said she couldn’t tell which of us wanted it more but she knew she wasn’t ready to see me out so she called: “Meferefun ancestor not her you can’t have her no you may not. She been down there already don’t you recognize her? Look! She been down there. I need her wit’ me. You gon’ have to see ’bout somebody else.”

There was a shimmer and then everything got still. No cicadas singing. No wind. No waves crashing. No seagulls vexing the shore with their itinerant squawking. Just quiet.

I felt an old conflict. That which I belonged to on earth and that which I belonged to on the other side had opposing ideas. I’d been feeling that tension my whole life. Nanny says I’m one of the old ones come right on back to see what moves we’ve made. She says I am the spy. She says I come from an old tribe, a protected tribe. She says I am unkillable. She says I am here to bear witness. She says I borrow from the lineage of Lazarus.

I was in Mami Wata’s arms. They were long. So long it seemed they coiled around me five times. A sacred rope. Her hair so long it had grown past where her feet would have been conjoining with kelp and coral reef; it glowed green. The snake in her arms whispered my name, beckoned me to stay. I wanted to oblige. But Nanny’s medicine is strong. We have a shine, her and me. Nanny is the tourniquet. She stitches things back together. She names and she un-names. Her medicine called me back. It has always called to me. Stronger, far louder, than the ghost rattle of the Atlantic.

Mami Wata didn’t keep me. And. I did not stay. Mami wants a reckoning. She wants remembrance. Some days she wants revenge. Every day she is hungry. Every day she mourns the bones beneath. Everyday she considers adding to them.

She, is what happens when you feed what is hallowed to the deep. She is the hex. The low growl in the dark. The thing that cannot stay. The thing that will not leave.

Folks will keep drowning in Chipley. They fed the babies to alligators here. Nanny says water wanna keep you. Nanny says prayer doesn’t really work here, only magic . . . only conjure.

Or a proper curse.

I’m just telling you what I know.

___________________________________________________________

Dominique Christina is an educator, activist, and author. She won the National Poetry Slam Championship in 2011, the Women of the World Poetry Slam Championship in 2012 and 2014, and the NUPIC championship in 2013. She is the author of four books of poetry: The Bones, The Breaking, and The Balm: A Colored Girl’s Hymnal (Penmanship Books 2014), This Is Woman’s Work (Sounds True Publishing 2015), They Are All Me (Swimming With Elephants Press 2015) and Anarcha Speaks which won the National Poetry Series prize in 2017 and was published by Beacon Press October 2018. Dominique believes entirely in the idea that words make worlds. Listen.

Dominique Christina is an educator, activist, and author. She won the National Poetry Slam Championship in 2011, the Women of the World Poetry Slam Championship in 2012 and 2014, and the NUPIC championship in 2013. She is the author of four books of poetry: The Bones, The Breaking, and The Balm: A Colored Girl’s Hymnal (Penmanship Books 2014), This Is Woman’s Work (Sounds True Publishing 2015), They Are All Me (Swimming With Elephants Press 2015) and Anarcha Speaks which won the National Poetry Series prize in 2017 and was published by Beacon Press October 2018. Dominique believes entirely in the idea that words make worlds. Listen.