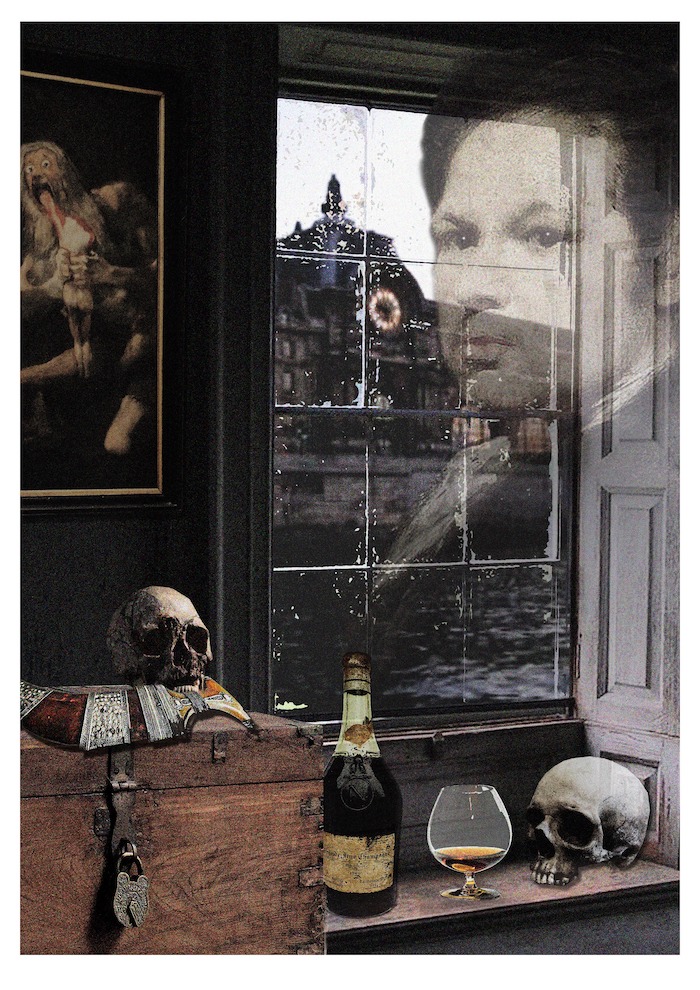

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

WINNER, Summer 2021

The Ghost Story Supernatural Fiction Award

BY BARNABY CONRAD III

Bellechasse, my friend in Paris, is the only non-medical man I know who keeps a collection of human skulls—nearly a dozen—randomly displayed in the library of his grand apartment overlooking the Quai d’Orsay. One winter evening he poured me a brandy and explained why.

“These poor bony fellows help mitigate the jealousy I feel for the masters,” he admitted. “By reminding me that they died just as I shall die . . . and that eventually we’ll all be forgotten.” He raised his glass to one of the skulls, and said, “Vanitas vanitatum, et omnia vanitas . . . chin-chin!”

Then he turned to me, as if there was some connection, and asked, “Still writing your great novel about the cuckolded beekeeper?”

I answered that, yes, I was, only I’d changed the protagonist’s occupation to lepidopterist, because my bed-hopping ex-wife had just published a novel called The Secret Apiary. “My agent said there was only room for one English novel on bee-keeping in every decade.”

“Sound advice, I’d say,” chuckled Bellechasse. “But don’t give up. You British never give up, do you? From Churchill to Fergie.”

I’d been working on this book for seven years with no end in sight. Taking a good swallow of brandy, I tried not to think about the skulls. Or the skull under my own balding pate.

Bellechasse’s father, Jean-François, had been one of the great French suspense novelists to emerge after the Liberation. A colleague of Malraux and De Gaulle, he’d launched his career with a feverish political novel set in Indonesia, where he’d briefly served as De Gaulle’s ambassador in the 1960s. Truffaut had directed the film starring Jean Gabin. More books and films flowed from the pen of Bellechasse père until a year ago, when he suffered a stroke. Two months later he died at his country estate near Poitiers and it was front page news for Le Monde and Le Figaro, not to mention the English-speaking journals. Some of the obituaries noted he’d been cryogenically frozen at a lab in Switzerland. Almost immediately a dutiful biography appeared, churned out by a refugee from the Deconstructivist camp. It neatly dovetailed with Gallimard’s re-publication of the late author’s collected works. There was even interest in London, where I live, or rather survive, as the editor of Insect World.

Bellechasse fils had grown up in the patriarchical shadow cast by this literary giant. Though he’d published a memoir about his own youthful trek through the jungles of Borneo, he had slithered sideways into art history, cultivating an expertise in Spanish painting. He was now a full professor at the Sorbonne. Thanks to the royalties on his father’s books, he had few financial concerns. Yet he still had his worries.

Bellechasse rose, filled his brandy glass again, and flopped back into the red leather chair. He tamped tobacco into his pipe. “For years I avoided any writing other than art history. Always feared the ghostly criticism of the old man. You wouldn’t understand that since your father was a doctor.”

Oh, wouldn’t I? But I let him continue.

“Always secretly wanted to be a novelist. Actually published a few short stories myself under a nom-de-plume: Pierre Darnoc. Not much success. Then, just a few days after my father died, I read a book about Borneo tribesmen who, upon the death of their father, bore a hole into the old man’s skull, cook the brains into a tasty stew, and eat it.”

“Oedipal revenge?” I chuckled.

“Good heavens, no,” he chuckled back.

I should interject that Bellechasse was fascinated by grisly news items about circus train wrecks in India and tales of cat ladies being consumed by their feline charges. He was anything but squeamish.

“For the tribesmen it’s an act of respect. And practical,” he said. “They believe it gives them the intelligence of all their forebears because the custom has been performed in an unbroken chain since time immemorial.”

“What a thing to do!”

“Not so bad, really,” he said. “Rather like calves’ brains if prepared properly. So I’m told. But let me tell you something quite exciting: Two months ago, while researching my book on Francisco Goya, I spent a week in Bordeaux. You know, that’s where Goya lived out the last years while completing the Tauromaquia series.”

“The bullfight scenes?”

“Exactly. After visiting the studio where Goya painted—now a sort of a musty house museum—I passed my afternoons drinking some lovely wine and poking through antique shops where I hoped to rustle up a really fine Napoleonic cutlass—you know my boyhood passion for blades.”

Indeed, one wall of his study was devoted to dozens of exotic weapons ranging from a Scots dirk to a dagger from Yemen whose handle was the horn of a rhino.

“Oddest thing happened to me in Bordeaux. Three nights in a row, I dreamed of a disembodied head floating in front of me, hovering like a balloon. I couldn’t see the face clearly until the last night. Towards dawn I recognized it as the face of Goya himself. Suddenly the vision was no longer threatening. It seemed to be speaking to me. When I awakened I felt a strange power infusing me, a rushing-in of ideas and colors. You know me—a man who deals in factual terms—yet I thought I was going insane! But in a good way.”

“How so?”

“I felt driven to write what was coming into my own head. While scribbling away it felt as if I were solving a mystery—through fiction—that has puzzled scholars for a century and a half. Have you read much about Goya’s life?”

“Truthfully, no. I just know the paintings.”

“Well, after fleeing Spain during the troubles, Goya lived the rest of his life in Bordeaux, dying finally on April 16, 1828. Odd thing: a few days after his funeral, the grave was disturbed and his body . . . well, someone had decapitated it.”

“Cut off his head? Why?”

“It’s a mystery. The head was never recovered.”

My mind moved quickly. “The skull on the shelf . . . you’re not saying—?”

Bellechasse raised his hand. “Heavens, no. But would you read what I’ve written about these visions?”

“Of course. Send me a copy.”

“Better yet—” He handed me a manuscript of a dozen or so pages. “It will only take a few minutes. You don’t mind? I must take the dog out for a few minutes of . . . relief. Back soon. Pour yourself a drink.”

Bellechasse stuck a pipe in his mouth, and went out of the library, closing the door behind him. A minute later, unseen canine claws clattered across the parquet of the hallway—a dachshund named Celine whose biting habits had made it unwelcome in social settings. After the front door clicked shut, I poured myself a brandy and settled back to read the story, which I share below:

Genius Pursued

By Henri Bellechasse

Two hours after midnight the rain fell steadily on the dark streets of Bordeaux. Misty halos encircled the few gas lamps not extinguished by the storm. A thin, hunched man lurched along the cobblestoned street. Rain slid from his hat, dripping into the collar of his ragged cloak. His boots were muddied to the ankles.

Clattering hooves sent the man into a doorway. He stiffened in the shadows, pressing his unshaven cheek to the rough portal. A swaying lamp appeared, held high by a mounted watchman. The man in the shadows held his breath. He could hear the horse worrying the rolling metal bit in its mouth. The lantern’s beam grazed the doorway, then passed on.

The man brushed wet strands of hair behind his ear. The long delicate fingers bore traces of paint: cobalt blue, alizaron crimson and burnt siena. His other hand clutched a blood-stained burlap sack filled with something heavy and round.

Stepping into the rain, the man scuttled down an alley rank with the scent of rotting fish. Rats roamed the gutters, skittering into the shadows. He turned the corner behind a patisserie, and picked his way to the rear of a stone building. He shoved a key into a lock, pushed the door open and stepped inside. Lighting the stub of a candle, he trudged up a flight of worn stone steps to another door, which required a second key.

Once inside he bolted the door and sighed with relief. Soon, he thought, I, Gustave Paget, will embark on a strange and marvelous journey. I shall be born anew.

It was a high-ceiling garret with rough beams and joists, serving as both a painting studio and living quarters. Paget gently placed the heavy burlap sack on a wooden table littered with small pots of paint and brushes. There was a troubled bed, a worm-eaten armoire, and a human skeleton hanging from a chain attached to a roof beam. Before the high dormer window stood a heavy easel bearing the unfinished portrait of an elderly woman with flushed cheeks and bulging eyes.

You again, thought Paget. The wife of a crooked watchmaker with social pretensions. “Aren’t you making the cheeks a bit full, eh?” he cackled, mimicking the sitter’s nasal whine. “And why have you made my little nose really so coarse, eh?” He answered the portrait, “Madame, if you wish it differently, I suggest you paint it yourself!” With that he tossed the canvas into a corner.

At thirty-four, Paget had spent the last decade in that twilight between aspiration and despair. He had attended the Beaux-Arts in Paris and graduated with honors for his masterwork, “Nectar of the Gods.” His life drawings were competent, his professors said, and his portraits were accurate if somewhat lifeless. Yes, the academicians had all agreed, he would be able to earn a living as a drawing tutor or a portraitist if he courted the gentry—more easily in the provinces, to be sure, than in Paris.

But Paget didn’t want to just be “respectable.” Had he not witnessed the public’s reverence for Carravaggio, Poussin, and the current favorite, David? To be known, to be lauded. To wear Parnassian laurels and earn the praise of poets. There was immortality in genius, and that is what he wanted. Then and now. A piece of genius.

Paget’s widowed mother had financed his travel to Florence, where he gained permission from the Uffizzi to copy the madonnas of Raphael and the courtiers of Bronzino. He slavishly copied the graceful hands, the curving lips, and the soulful eyes that at times made him weep. So close to greatness! Oh, to possess it!

But he also spent his mother’s money on fine clothes, in foolish wagers with sharpies, and cavorting in taverns where students cried “wine for all!” There had been women, but few were ladies. The years passed in a flash. He was no longer a student, and his friends drifted away. An unfamiliar poverty forced him to fresco music rooms in the houses of merchants, to restore old paintings, even to paint flowers on porcelain.

He was thirty when his mother died. He moved back to Bordeaux, the town where he had been born, and set up a garret studio in the building owned by Madame Soulanges, one of the few who remembered that Paget’s father had been a gentleman, and that he had died valiantly with Napoleon’s cavalry in Poland.

On the ground floor of the Soulanges building was a tavern, Le Vert Galant. It was here that Paget sometimes met with Marcel Deyrolles, an art dealer from Paris. More importantly, it was here that Deyrolles introduced Paget to Francisco Goya.

The Spanish master, then in his late seventies, was sitting at a corner table with a dark-haired woman whose lovely smile revealed a naughty gap in her teeth. Goya did not stand when Paget and Marcel approached, but he motioned the men to be seated. Paget could barely suppress his awe. This was Goya! The greatest living painter of Spain and, perhaps, of France.

Although very deaf, Goya had been drinking and was in a talkative mood. His dark eyes glistened with amusement from under the heavy eyebrows. His face was full but still rugged, hedged by thick sideburns, and his dark eyes twinkled as he spoke of the bullfights he had seen that day.

“A big gray beast with horns like a hayrack came out and Arcarruz, that cowardly Basque, lanced him in the belly so the entrails tumbled out like sausages. The bull turned and toppled him off his horse. If the other caballero hadn’t caused a diversion, the beast would have pinned him like a fly. Victoire here likes the fights, don’t you, my lovely?”

Victoire, whose line of employment was never mentioned, smiled.

“I suppose you’ve been to the corrals and made life studies of the bulls for your paintings?” said Paget respectfully.

“I don’t understand the question,” said Goya cupping his ear.

“I mean do you make anatomical studies of the animals, to get the muscle structure correctly—”

“Dios mio, this man has a weak voice,” he said looking helplessly at Deyrolles. Paget was embarassed, but leaned forward and shouted the question.

“Ah! Studies, you say? That’s just academic procrastination. I could paint the bulls blindfolded! You either have a feel for them or you don’t. It’s all right there in the ring. You look, you remember, and you paint. Ever been to the fights?”

“No, I never liked the sight of blood.” Paget immediately wished he had lied.

“Well, at least you’re man enough to join me in a glass of blood-colored wine, no?”

Everyone laughed, but the cut had been obvious. Goya now only addressed the others, even turning his chair away from Paget. Then the master recounted his portrait sessions with the Spanish royals.

“His Majesty timidly asked, ‘Why have you made my eyes so far apart? I look like a toad searching for a fly.’ To which I replied, ‘I beg His Majesty to consider that the distance between his noble eyes are an indication of broad vision contemplating the vast realm of España and her great future.’ The King rubbed his hands together. ‘Hmmm. You’ve a point there, Goya, you’ve a point.’ And afterwards everyone who saw the portrait whispered that he looked like a big fat toad waiting to catch a fly!”

A week later, Deyrolles brought Paget to Goya’s studio at the house the master occupied on the edge of town. It was a late autumn afternoon and the courtyard was scattered with leaves. A servant showed them to the door of the studio. Goya, clad in a blue painter’s smock, welcomed them in. The girl from the tavern, Victoire, was also there, dressed in a Spanish costume with a black lace mantilla on her head. Paget wandered around the studio as Deyrolles discussed a business matter with the Spanish master. There were dozens of canvases leaning against the wall and stacks of folios containing etchings and preparatory drawings.

A shiver went up Paget’s spine as he pored over the artifacts of this prodigious mind. Genius had been humanized. It was standing just twenty feet away! Anger struck Paget. A great unfairness had been perpetuated by God when he gave one man such a gift. Why not to Paget? Hadn’t he given his soul to Art? Allowing this rumpled old Spaniard more than his share of the Muse was an abomination.

Goya displayed a half-finished painting on his easel. “The bulls enchant me, but today I paint this lady—esta señorita estimada. Victoire, my dear, please resume your position.”

Victoire dutifully sat in the chair on the raised platform. Paget watched as the master set about completing what would later be called “Maja at the Bullfight.” He painted more swiftly than Paget had ever seen before. Then Goya would step back, squint, cock his head, and attack the canvas again. Those dark brown eyes glistened as if infused with a chemical released from his brain. His body vibrated as he lay down layer after layer of paint with bold, precise strokes. The only sound was the rattle of the easel as he brushed in the black of her gown.

In ten minutes Goya completed the figure. Twenty minutes later he completed the face. In a daring move he began to brush a fine lace over the likeness of Victoire. A cautious painter would have waited for the face to dry; that way he could wipe away any mistakes and try again. Paget barely stifled a cry for the master to be prudent.

But Goya unfurled the lace from the end of his brush. Five minutes later he tossed his brushes into a bottle of turpentine, and faced his audience of two. “I believe I’m finished for the day.” He stepped back, dabbed his brow with a cloth, and motioned for Victoire to step down.

“Bravo!” said Deyrolles.

“That was brilliant!” blurted Paget in spite of himself.

“It’s partly luck,” said Goya. “You see, I’m a very old man. God is kind to old men who try their best in love and painting. Victoire, are you listening?”

Paget went back to his own studio with renewed energy. He saw Goya only once more, on the street, but avoided him. Contact with such genius could inspire him, but it could also burn his ego. He tried sketching the local bullfights, but the pictures, as Deyrolles bluntly put it, looked like second-rate Goyas. Paget traveled to Italy again and tried landscapes and farm scenes, but he did not have a rapport with country people. There was a bad incident with a dairy cow, and in the farmer’s insults about un-natural acts with bovines he thought he heard the mocking voice of Goya, master of the bulls. Again and again he stared at his stiff, over-worked canvases and saw only the absence of Goya’s deft brush.

In Venice Paget tried to shake Goya’s influence by adopting Bellini and Titian as his new gods, but he contracted malaria. Waking from his feverish dreams, he opened his hotel window and heard the tide lapping in the canal. Time was slipping away. In just a few years he would be old. Weakened by recurring attacks of the fever, he was wan and hollow-eyed when he returned to Bordeaux. He began to drink heavily.

After he tumbled down a flight of stairs, his landlady Madame Soulanges sobered him up with steaming pots of chamomile tea. His binges allowed him only fleeting days of sobriety in which to paint a lack-luster portrait for food. He slept badly, beset by nightmares. One morning he recounted to Madame Soulanges that in his sleep he had entertained a gathering of greatness including Rembrandt, Titian, and Leonardo. “They asked me to pull up a chair—a fellow artist—but they turned away Goya. No, Goya was not good enough.”

Sometimes he wandered at night by the river or in the wooded hills surrounding the city. From time to time Deyrolles still came down from Paris to Bordeaux by coach to visit Goya, but he no longer called on Paget.

One April morning Paget stumbled into the street after a three-day binge and was surprised to see a familiar face—Deyrolles. Was it a year or two years since he’d last seen him?

“Marcel!” called Paget. “T’is I, your old friend and genius. What brings you to our fair city?”

Deyrolles was shocked by Paget’s seedy state. “Haven’t you heard?” said the art dealer.

“Heard what?”

“Goya is dead. The funeral is tomorrow. I must leave you.” He brushed past the wide-eyed Paget.

Goya, dead? Although he had not seen the Spaniard in two years, the announcement came as a shock. How could he, Goya the Immortal, die?

The funeral was grand and respectful in the cemetery. The crowd was enormous. Not many people noticed the stranger in a tattered cloak who lurked behind a crumbling mausoleum.

Paget left the cemetery before the ceremony ended and bought a bottle of cheap brandy. Back in the garret he drank alone, saluting his slack-jawed skeleton with toasts to Goya’s life, Goya’s death, and Goya’s art which would live on as a testimony to his genius. On and on into eternity.

It was then that Paget experienced a clarity he had never felt before. The moment itself was an act of genius. Voilá! It took a piece of genius, he reasoned, to beget genius.

From a butcher he bought a used meat cleaver, then found a gypsy to sharpen the blade. For several hours, he prepared his studio. He stretched and primed a linen canvas with rabbit-skin glue. He ground new paint. Waiting for nightfall, he was undaunted by the heavy patter of the rain on his roof.

After midnight the thunder stopped. The rain began to ease. Paget dressed in the same grimy clothes he had worn for the last year. Pulling on a cracked boot, he saw his big toe emerge through a hole in the leather. He daubed it with brown paint, and cackled. He donned his old cloak and battered hat. Then he slid the meat cleaver into a burlap sack and went out the door.

It was still raining lightly when Paget’s lantern illuminated the gates of the cemetery. His boots sank in the mud as he followed a path through the tilting tombstones and vine-shrouded cenotaphs. He found the temporary mausoleum where Goya was interred; it had been loaned by a wealthy patron until the master could be honored properly. Rain-battered bouquets of white flowers lay in the mud like cast-off petticoats. He pushed open the iron door. The stone chamber echoed with his gritty footsteps. He turned up the flame in his lamp and set it on a ledge. Shadows flickered on the walls.

There was no time to waste. He sized up the marble cover of the sarcophagus, threw his trembling shoulder into it, and slid the stone sideways. Two more shoves and the marble slab tilted, crashing to the floor.

Paget looked down at Goya’s gray face, bleached of life. He felt the faintest hint of conscience. But only for a moment. Grabbing the corpse’s lapels, he lifted the body until the head lolled over the edge of the sarchophagus. He slid the cleaver from the burlap bag. Treat him like a piece of mutton.

The blade sliced through Goya’s silk collar and throat, biting deeply into the bone. It took three more hacks. There was blood, but not much. The body slid back into the box. As he hoisted the head by its thin gray hair, the meager strands parted. The head hit the stone floor with a melon-like thud, then rolled. Paget whined, fumbling for it. Damage? By the light of the candle he saw that only the forehead was slightly abraded. No harm done. What a prize! He shoved it into the sack, grabbed the lantern, and left.

Three months later, a woman wearing a hat that had not been fashionable in Paris for over twenty years crossed the Rue de Rivoli and entered the office of the art dealer Marcel Deyrolles. She announced herself to a secretary at the front desk. “Madame Soulanges of Bordeaux, with the paintings of the late Gustave Paget.” Behind her a porter wheeled in a cart loaded with two large wooden crates.

Deyrolles emerged from his private office. A month earlier he had received a quaint letter from Madame Soulanges, whose charmingly provincial mode of expression, he now saw, was consistent with the woman herself—hat and all. As she rose from the chair to greet him, he bowed, and bid her resume her seat.

“Ah, then, madame, may we see the pictures?” he said. His assistant pried open the crates, careful that splinters did not catch his silk waistcoat. Twenty-two canvases were lined up against the wall. There were landscapes and portraits, some unfinished. There were two copies of Titians—probably student works—and three clumsy sketches of bullfights. They were unframed and, thought Deyrolles, they would probably remain so. What had the poor man been doing with his life?

Then a dark portrait caught his eye. Deyrolles flipped his monocle in place and stiffened like a setter on point over a partridge. “Where, Madame, did you get this one?”

“It was propped on the easel in dear Paget’s studio. I found it after they pulled him from the river. Drowned himself in the river, poor soul. Oh, monsieur, it was a sad life.”

“Yes, yes, very sad indeed. . . .” He intently inspected the surface of the canvas, ignoring the others. “But this picture . . . You say it was in his studio?”

“Like I said, monsieur, propped up on the easel. Most likely the last one he ever did.”

Most unlikely, thought Deyrolles. Though he had never seen it before, it was unmistakably the work of Francisco Goya. It was surely a self-portrait of the master in his studio, tightly framed from the chest up, with a mysterious background populated by strange figures flying about his head. Behind him on the left, floating in the darkness, was a bull straddled by a skeleton and on the right appeared a mysterious maja in black whose face was covered with a spidery, gossamer veil. Similar, remembered Deyrolles, to the portrait of Victoire that he and Paget had watched Goya execute in his atelier that long-ago afternoon in Bordeaux. What made the self-portrait so unusual was that the maestro’s eyes were closed, as if he were dreaming the phantasmagoric scenes surrounding him. What was it Goya once said? El sueño de la razon produce monstruos. The sleep of reason produces monsters.

It was a masterpiece, a great late work. But what was it doing in Gustave Paget’s rotten little garret? He was a pauper and Goya certainly wouldn’t have given it to him, would he? No. There was only explanation—theft. Crazy Paget had stolen it, perhaps during the funeral itself.

Deyrolle flipped the canvas over. Written in charcoal was this: Goya par Gustave Paget, 22 Avril 1828.

What kind of farce was this? Paget signing his name to such a picture? It was so obviously by Goya! The signature of a flea hitching a ride aboard the genius of a lion. But the date? Goya had been dead for almost a week. The crazy fool wanted a place in the museum so badly he couldn’t even get the date right.

Madame Soulanges watched Deyrolles anxiously. “As I said, monsieur, the paintings were all left to me, official-like, they was. He owed months of rent. The notary’s document is right here in my purse.”

“I have full faith in your representation, madame,” said Deyrolles, but the dialogue in his mind continued with greater urgency. If the picture was reported stolen there would be legal complications. The Goya family was not easy to deal with. And the lawyers. Better to just give the woman a good price for the whole shabby lot and keep things simple.

“Do not trouble yourself, chere madame. I will buy all the pictures and you’ll be rid of any further worries. I’m sure the arrangements will be satisfactory.”

Deyrolles drew up the necessary documents, produced the cash, and smiled as she cooed over the sum. When she had gone, the assistant asked, “Monsieur, what shall I do with the paintings?”

“Take the three best and sell them through that flea market scoundrel. Burn the rest. All except this one.” He picked up the portrait of Goya.

The assistant looked puzzled. “Burn them? But sir, you just bought them.”

“No, young man, I bought this one,” he tapped the dark portrait. “The others are worthless. No more questions. Do as I say.”

After the other paintings were gathered up and removed, Deyrolles picked up the self-portrait and turned it over. With a razor he gently scraped away Paget’s signature and the day and month. Now it simply read Goya 1828. That would work. A self-portrait painted just weeks before that crippling stroke sent Goya to his death bed. Deyrolles made plans for the picture—a certificate of authenticity, a coat of varnish, and a noble frame. Wait a few months out of respect for the dead, then contact a few of the Spanish grandees living in exile in Paris. He mentally composed a letter: “Since the master painted your late wife, the esteemed duchesa, I feel sure that Your Grace will want to consider this last magnificent self-portrait for your collection. . . .”

Deyrolles was pleased with the morning’s work. From the back of the building came the first sour whiffs of burning canvas. How unpleasant the smell was. He shut the door, looked back at the Goya self-portrait, and smiled. He suddenly thought of Gustave Paget. Thank you, poor old sod, for giving me this little bit of genius.

Bellechasse returned from walking the dog just as I finished reading the manuscript. Again there was the clatter of unseen canine toenails in the hallway, a door closing, and the dachshund was safely banished. My old friend entered the study and removed his overcoat and scarf. A light dew speckled his long-ish gray hair.

“Well?” he asked.

“It’s a rather good tale,” I said. “Vivid. Almost real.”

“Real—in what way?”

“As if you’d lived it yourself. Oh, not that you were a second-rate alcoholic painter in Bordeaux, but that business in the mausoleum—all that chopping with the cleaver, and the head bouncing on the stone floor. Ghastly! Still, it’s a wonderful old-fashioned tale.”

“Old-fashioned?” His brow knit.

“A bit like those horror stories your father wrote in the Fifties. If I didn’t know better, I’d have guessed it was one of them. Easily as good. Excellent, really.”

The look on his face was peculiar. “As good as my father’s, you say?”

A certain glint in his eyes gave me the strangest sensation. “Perhaps,” I said, “that wasn’t what you wanted to hear.”

“No, no. Quite all right, ” he said. “To hear the voice of another writer, a better writer, more clearly than your own, even if just for a few hours, until the story is told, is both a gift and a curse, but certainly better than hearing no voice at all.”

“Another writer’s voice?” I said. “I don’t understand.” I walked over to the bookshelf where he kept the collected works of his father. Among the volumes sat one of those skulls. It was quite clean and fresh with no missing teeth, unlike the others. I started to reach for one of the leather-bound books. Instead, on a peculiar impulse, I grasped the skull itself. I turned it in my hands, remembering what Bellechasse had said about the tribesmen eating the brains of their ancestors. There was a neat inch-wide hole carved in the back of the skull. It had been incised rather carefully with a sharp tool.

“Remarkable how skilled those Borneo tribesmen were,” I said. “Cutting through the skull with primitive instruments.”

“Much easier when the bone is still wet, of course,” said Bellechase. “It only becomes brittle later.”

I looked at the skull’s teeth. There were three gold fillings in the molars. That seemed odd. But, of course, they had plenty of gold mines in Borneo, right? And perhaps a do-good dentist went out with the missionaries, no? I was just about to say as much when I thought I heard the grating of metal on bone. Turning around I found Bellechasse scraping the bowl of his pipe with whatever the instrument is that pipe smokers use.

“Have much trouble getting this old boy out Borneo?” I said, hefting the skull. “Customs and what not?”

Bellechasse put the pipe aside and stood up. He seemed to be studying me now very carefully. Almost, it seemed, as if he were crediting and debiting our shared confidences over the years. It made me uncomfortable, so I reverted back to my role as an editor. “I don’t know where you’d publish your story these days, but it’s damned amusing in a macabre way.”

Bellechasse came over to where I stood. “Thanks for reading it,” he said. “But let me have that one, please.”

He gently took the skull from my hands, and cradled it as a father might handle a sleeping newborn. “Actually, this fine fellow,” he sighed, “wasn’t from Borneo.” He carefully placed the skull on the shelf next to his father’s books. Then he looked back at me with a sad, tender smile.

I think my eyes must have opened very wide. “My God! You don’t mean that . . .?” I couldn’t finish the sentence.

He smiled gently. “A little more brandy before we go over the Goya story? I’m very impressed that you understand the subtext.”

___________________________________________________________

Barnaby Conrad III has published ten books of non-fiction, including Absinthe: History in a Bottle (Chronicle Books) and Ghost Hunting in Montana (Harper Collins). His monograph Jacques Villeglé and the Streets of Paris (Inkshares.com) will appear in summer 2021. He lives in Accomac, Virginia, where he is working on a novel. Contact: BarnabyC@aol.com.

Barnaby Conrad III has published ten books of non-fiction, including Absinthe: History in a Bottle (Chronicle Books) and Ghost Hunting in Montana (Harper Collins). His monograph Jacques Villeglé and the Streets of Paris (Inkshares.com) will appear in summer 2021. He lives in Accomac, Virginia, where he is working on a novel. Contact: BarnabyC@aol.com.