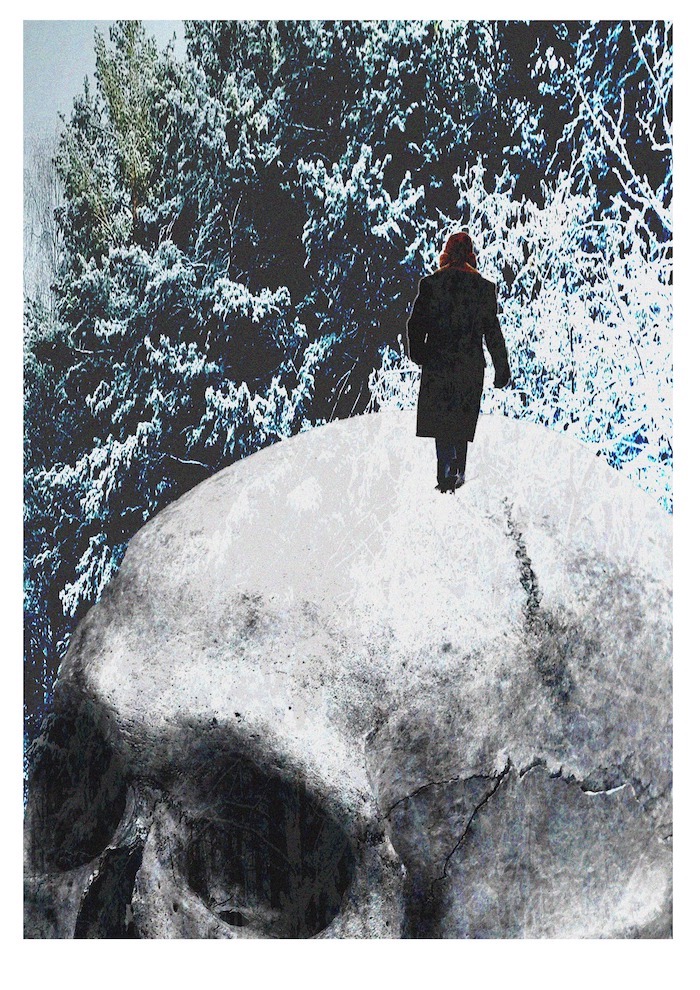

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

HONORABLE MENTION, FALL 2021

THE GHOST STORY SUPERNATURAL FICTION AWARD

BY MATHEW SWEET

The snow has settled in drifts high up the trunks of the trees at the edge of the forest, deep and powdery, and pulling the sled becomes increasingly arduous. Kovac feels a bead of sweat break away and slip down his side, and without stopping he stretches out his shoulder to absorb the drip of it into his woollens. He had lingered too long in the village, mostly in the vain hopes that one of the girls might appear either in the downing market or the alehouse, but they had not, and he had wasted the daylight chatting idly with Raskovic, and then later Peter Andreyev. Andreyev had never been engaging company, but since losing both child and wife to sickness, he had become difficult for even the most charitable to tolerate. Andreyev would talk at great length about his ailments, physical and financial, providing a detailed litany of woes and discomforts. It was known to all that at the heart of this was his great loss, of course, and a grief he could not fully meet. The entirety of his family taken in a single season. But that fact alone couldn’t mitigate the misery of the man’s company indefinitely. As unwitting as any other parasite, he would leverage the hooks and fangs of pity to drain the unsuspecting of their time, and such had been the case with Kovac this night. Kovac had run his skinny fingers through his beard with growing rigor in order to supress his frustration as it threatened to spill over into sour words. The thought of Andreyev’s horrible loneliness kept him there, kept him polite, and kept him late.

And so it is that he finds himself at the top of the hill, at the edge of the forest, armpits damp beneath the layers, as the last of the sun falls away behind the blackened hills.

Kovac doesn’t like the forest by night. By day it was a different place, and as a youth he’d spent joyful hours there among the pines, far from adult eyes. After sundown though, it took on a different feeling. As with any patch of trees near a secluded, provincial community, there was talk among the children, of wolves and witches, old folklore whispered and mutated through generations. The rush of fear that binds a huddled group is all fine fun until the walk home that must be made alone. In company, the mind probes the strange allure of the supernatural with excitement in shared tales of darkness and disorder. Once the group has dispersed, however, and every shadow looms long, a new sense takes over. A murky dread that warns against every crooked silhouette, every gust that lifts the leaves behind the hedgerow. Even the silence takes on a new aspect once the primordial guard is stirred. It warns that there are things beyond this mundane life. Things you don’t want to glimpse, don’t want to even think about. Perhaps thinking about them brings them closer, like a magnet, like a siren’s song. And so Kovac trudges between the pines, the ropes of the sled taut across his chest, and he tries not to think about anything except his mother, and his sister Zascha, waiting at home with a warm fire crackling in the hearth.

Though the forest by night is as unwelcoming as a place might be, the trees at least provide some shelter from the cruel winds that would otherwise be whipping through him and chilling his bones. There is a tranquillity here, albeit a disquieting one. The diffused breeze stirs the canopy, and the peace is broken only by Kovac’s heavy bootfalls, and the grind of the sledrails through the crusted snow on the forest floor. The sled digs through the accumulation and catches on something unseen, causing an uncomfortable yank on the harness. Kovac pulls down the scarf that covers his mouth, and takes a deep, icy breath. The rolling eddies of his expiration seem to illuminate the night. He takes the hand shovel from the front of the sled and scoops away the snow around the rails, where one of them has caught on an exposed root, twisted out of the soil to form a snag that runs the width of the path. He pushes the sled back to free it, then he lifts the front up and over the obstacle. Light comes more from below than above now, the pasty grey of the forest floor glowing beneath his feet, while above, the meagre moonlight is muted by clouds. Before setting off again, he knocks the built-up frost from the back of the sled, then he looks to the heavens for a moment. The silence is overwhelming.

He pushes on into the forest, not yet halfway through the journey, and a few trudging minutes later he finds himself looking out into a wide clearing. He doesn’t recall ever seeing such a perfectly clear, perfectly rounded area along this central path before. Immediately his thoughts go back to darker places, and he looks about as if expecting to see someone there. This cleared circle of softly luminous snow is corrupted by a black spot in the centre, maybe six feet wide, which at first looks to be a patch where the snow has melted away. He crosses to it, the sled dragging along behind him. He kicks a little snow into the patch of black and sees it vanish. It’s a hole.

“Ilya? Is that you?”

He recognises the voice that comes from the hole, calling his name, out here in the icy forest in the middle of the night. It’s his mother. His mother who has been unwell these last two weeks, and should be tucked up safe and warm in their home, another mile away on the other side of the forest.

“Ilya, you must come down here.”

His mind is spinning now. It makes no sense. “Mother?” He feels foolish, even as he says it.

The reply comes with whispered urgency. “Yes, Ilya Kovac, it’s Mother. You must come down here!” Kovac feels a tightening in his gut.

“What . . . what are you doing down there?”

“I’ll tell you when you come down. Come on now. You must come down here!”

He finds himself looking uselessly around again, as if some forest creature might emerge from the trees and offer guidance. He kicks more snow into the hole and watches it disappear into the darkness. “How deep is it?”

“It’s not very deep. Come on now. Just sit on the edge and jump down.”

His heart is racing. She calls again, quietly through gritted teeth. “Come on!”

It makes no sense at all. Kovac wonders if he’s lost his mind and is imagining the whole thing. Maybe there was something bad in the ale, and his mind is polluted with fevers. Andreyev had said the taste was sour. “Why . . . why are you in a hole? What’s going on here?” Everything seems fluid and dreamlike. He feels sick and dizzy.

There is a long pause, and then the voice says very softly and slowly, “I told you before. I can explain when you get down here.”

Kovac takes off the straps of the sled harness and crouches down. He waves his hand in the dead air of the hole, which still looks so much like a patch of black soil cleared of snow. Kneeling, he takes a handful of snow and compacts it into an icy ball, and he drops it into the hole and listens for its landing. It’s deep. Twice his height, at least. The voice of his dear, sweet mother, who he last saw dozing unwell in a makeshift bed near the fire in their home, exhausted from a cough that wracked her bones, her voice comes back again from below the ground and whispers urgently, “Come on! What are you waiting for?”

He peers into the blackness of the void, and then he’s aware of a smell, like the butcher’s shop, but sweeter and sickly. The voice comes again, closer now, and angry, the words are quietly spat out. “Come on!”

He scrambles up off his knees. His mother has never sounded like this, never hissed so furiously at him, even when it was deserved. He stands over the hole, and says, “No.”

Another voice from out of the blackness beneath now, a man’s voice, bellowing out, boiling over with raging fury, “Ilya! Get down here right now!”

His father. Dead two years.

The sound reverberates around the forest, and without conscious thought Kovac turns and runs, back the way he came, leaving the hole and the sled behind him, his breath coming in great gulps, the back of his throat frozen sore, and he keeps on sprinting away from the clearing as fast as the powdery snow will allow, back to the village, back to humanity. After a few minutes he can no longer sustain the pace, and he settles into a jog, and then he’s walking at speed. He thinks of the sled, left there in the middle of the forest, and for a second he thinks about going back, strapping up the harness and running in the opposite direction, towards his house and safety, but the sound of his father’s voice still plays in his mind, how the piercing bite of it echoed briefly through the forest, an explosion in the darkness.

At the edge of the treeline he looks down the slope toward the village where the cluster of buildings nestled in the valley make up a shadowy impression of abstract shapes. No lights. No smoke from chimney stacks. He trudges steadily down the deep snow on the hill, along the path beside the plain, and then he’s in the empty streets, silent and blue in the weak light of the muted moon. No sound, no smell of firewood burning. He walks up the street toward the tavern and sees no one. The tavern is dark. He scratches the frost from a windowpane and cups his eyes to peek inside. Nothing. Shadowed shapes of tables and chairs. Nobody home. He steps into the middle of the street and calls out, “Hello?” and suddenly thinks that maybe it’s much later than he thought and maybe everyone is silently asleep in their homes, and he feels foolish for a moment, feels that someone might call out of a window and tell him to shut up and leave the good people in peace.

There is movement behind him. A diminutive figure scurries toward him with coattails flapping. Kovac puts his hands up in defence and the frozen air seems to catch in his throat.

“Kovac! Kovac, is it you?”

“Andreyev? Thank god! Yes, it’s me. Where is everyone? I saw something in the woods, Andreyev. . . .”

Andreyev grabs his sleeve. “No time for that Kovac, come with me! You must help!” Andreyev is sobbing.

Kovac follows as Andreyev drags him up the street. “What is it? Where are we going?”

“My wife, Kovac! You must help!” he says, as they run up past the church where the hoarfrost coats the wooden cross and hangs in big melty drips, then across the square to Sadovaya Street.

Kovac yells, “Your wife? Where is everyone, Andreyev? What’s going on?” and then they are at Andreyev’s house, where Andreyev bounds up the stairs into a small, musty bedroom, steeped in darkness. They are both out of breath, Andreyev bent over with his hands on his knees, Kovac leaning against the dresser. He thinks about the voices in the hole in the forest. He says, “What is this, Andreyev? What are you saying . . . your wife?”

Andreyev, his back against the wall next to the frosted window, points to the rickety bed and says, “Under there. Look.”

“Your wife is dead, Andreyev.”

“Look! Look and see!”

Kovac lowers himself onto his side and he looks into the pitch black under the bed. At the back he sees some old sheets bunched up, and as his eyes adjust, he sees they’re not sheets, but the bundled pleats of a smock. Atop the body he sees a head without hair, turned away from him toward the wall. He says, “My god. What are you doing under there?” He looks back to Andreyev, and says, “Is it her?” but Andreyev has gone.

“Andreyev? Where are you?”

From under the bed, the woman’s voice whispers, “Kovac! Please help!”

He kneels on the floor and dips his head down to see her again. “What are you doing under there? What is this now?” She looks alarming in the dark with her back to him, a pale and hairless head, barely discernible.

“Kovac you must help! Help pull me out, won’t you?” A frail and scraggly hand reaches backward awkwardly toward him with fingers outstretched. “Take my hand, Kovac! Pull me out!”

He smells the same smell from the woods, like the butcher’s shop, but mixed with something rotten. He gets to his feet, away from the bed, and he calls out to Andreyev. He checks every room in the house, upstairs and down, but Andreyev is gone. Out in the icy street, the snow has begun to fall again, and a spiteful wind whips it up into spiralling columns that bound up and across the road. Kovac calls out again, but he knows that Andreyev is not here. He takes a final look up to the bedroom in the house, the window still frosted over, and he decides he will take the long way home, along the river road and across the bridge.

He hurries away from the desolate houses and the emptiness and the figure beneath the bed. His hands are deep in the pockets of his overcoat and he keeps his shoulders high, tense against the chill. The snow comes thicker now, obscuring the view, and once he’s past the rickety fence that borders old Grigory Novotny’s place there is little to guide his way. He watches his feet and tries to focus on maintaining a straight path, and he starts to sing a song about a fish that his father used to sing and then he thinks of the voices in the hole in the forest and he stops singing and he keeps walking and walking.

The snow is a blinding wash. He pushes into it for hours. He should have reached the bridge by now, but something is not right. There is nothing but whiteness, on and on. He wonders if this is how it will be forever, lost in this blank void, and he wonders if he will die here. His chest and throat ache from the frozen air and his eyes are almost entirely closed when he finally reaches the fence and tracks it to the gate, and then he is through the door and he is home. He slumps to the floor, no longer able to stay upright, lungs ablaze. The room is cold. He lies on his side, and as his eyes close, he sees there is no fire in the hearth. The house is silent except for his strained, raw wheezing, and the howl of the ragged wind outside.

“Ilya! Ilya is it you?” The voice of his sister Zascha, coming from the basement. There is desperation in her tone, but she speaks in a hush, as if trying not to wake someone. It is all Kovac can do to utter her name in response.

“Zascha. . . .”

The voice comes again. “Ilya! Ilya, please! Come down and help me! I’m here in the basement, Ilya!”

Kovac forces his eyes open and shakes himself awake and wipes the frosted snow from his beard. He pushes himself upright onto all fours first, then leans back against the door. Across the room, he sees the door of the basement is closed. He clambers to his feet and staggers slow and unsteady across the room, and as he reaches for the doorknob a hand comes from the dark alcove to the side of the door and fastens tight around his wrist. His sister, Zascha, her eyes wide, her skin as pale as the snow outside, emerges from the shadows. She shakes her head at him violently, still holding onto his wrist, and with her other hand she pushes a finger against her lips, urging him to silence. Her unmistakable voice comes again from somewhere behind the closed door in front of them, somewhere beneath them.

“Ilya! I need your help! Come on!”

Kovac leans against the wall, unable to remain upright. Zascha pulls his arm around her neck to support his weight, and half drags him down the hall to the bedroom. Their mother lies there, bundled up in blankets.

She whispers, “Ilya! Oh my Ilya!” He goes to her and kneels by the bed and takes her hand. “What’s happening, Zascha? The voices still?” Zascha nods. “Are they angry? I couldn’t hear them.”

Zascha says, “Not angry. It was my voice, calling to Ilya. Calling him down to the basement.”

Kovac’s voice is tremulous. “What is happening, Zascha? What is this?” There is a smell here like in the woods, bitter and metallic.

Zascha strokes the back of her mother’s hand as she speaks. “A few hours after you left. When the sun went down. Mother took a turn. And then I heard her voice calling, from out there. She was here in bed the whole time, but I heard her. And then after that . . . there were others. Some angry. They said terrible things, Ilya. I was afraid to open the door.”

“You mustn’t!”

“We won’t, Mother. Not until we have someone here. The men from the village. The priest. I have to fetch them, Ilya.”

“I couldn’t find anyone in the village. It was empty.”

“What do you mean?”

“There was no one there. I don’t know. I heard voices too. In the forest. Everything has gone wrong, Zascha.”

“No one in the village?”

“No one. Just . . . Andreyev was there, but he left. . . .”

“Then I’ll go over to the Leonovich farm. I’ll get Leonovich and his boys and we’ll come back here and one of them can go south to Sviyazhsk and get the officer and the priest and whoever else. Okay?” She begins to dress for the journey, tying the top of her rubakha as high as it will go.

“Zascha . . .”

“You’re in no state to go anywhere, Ilya. You must stay with Mother. She needs you.” She tightens the leather strip around her waist and puts on her mother’s heavy winter coat.

“The storm . . .”

“What else can we do? Wait here for whatever is down there to finally come out? Give me your scarf.”

Kovac is exhausted and has no ground for protest, and soon Zascha is out into the whiteness. She strides forward into the heavy wind, clasping her collars tight to her neck. She follows the slope of the road down to the crossroads and eventually finds the ditch that borders the fields to the west. Snow comes in heavy wet clumps and the wind cuts right through the furs and right through her bones. Progress through the thick snow is slow and tiring and the distance seems much farther than it ever has. Strange noises penetrate the deadening muffle of the wind, distant groans of some huge machinery shifting. It is difficult to not feel lost in this great void of nothingness. Difficult to not lose heart.

For hours she wades through the snowstorm. It feels like it may never end. She should have come to the edge of the copse by now. Should have met it hours ago. Should have passed through it and come to the Leonovich farm and gone in inside and found warmth and safety and help. But now there is just snow and more snow and nothing to be seen ahead. She feels as if she were now just a vessel for this forward movement. No longer herself, no longer a thinking, feeling human, just a body, moving forward, always forward, into this empty white world. It has taken so much longer than it should have. Distance is different now. As if in this vast snowstorm, the world has somehow spread itself out. As if the space between everything has expanded, and continues to expand. As if the connections between all things are stretching out thinner and thinner. As if the house far behind her has lain empty and silent for days, no movement there except the flowers, withered and dried in a cup by the window, stirred into swaying by the wind that cuts through under the door.

___________________________________________________________

Mathew Sweet is a writer and librarian from the south of England, now living and working in Ohio. His written work explores mortality and transcendence, probing the dark edges of human self-knowledge within an ambivalent cosmos. He likes kitties and also doggies. “They Are Gone From Sight” is his first published short story.

Mathew Sweet is a writer and librarian from the south of England, now living and working in Ohio. His written work explores mortality and transcendence, probing the dark edges of human self-knowledge within an ambivalent cosmos. He likes kitties and also doggies. “They Are Gone From Sight” is his first published short story.