WINNER, Fall 2017

The Ghost Story Supernatural Fiction Award

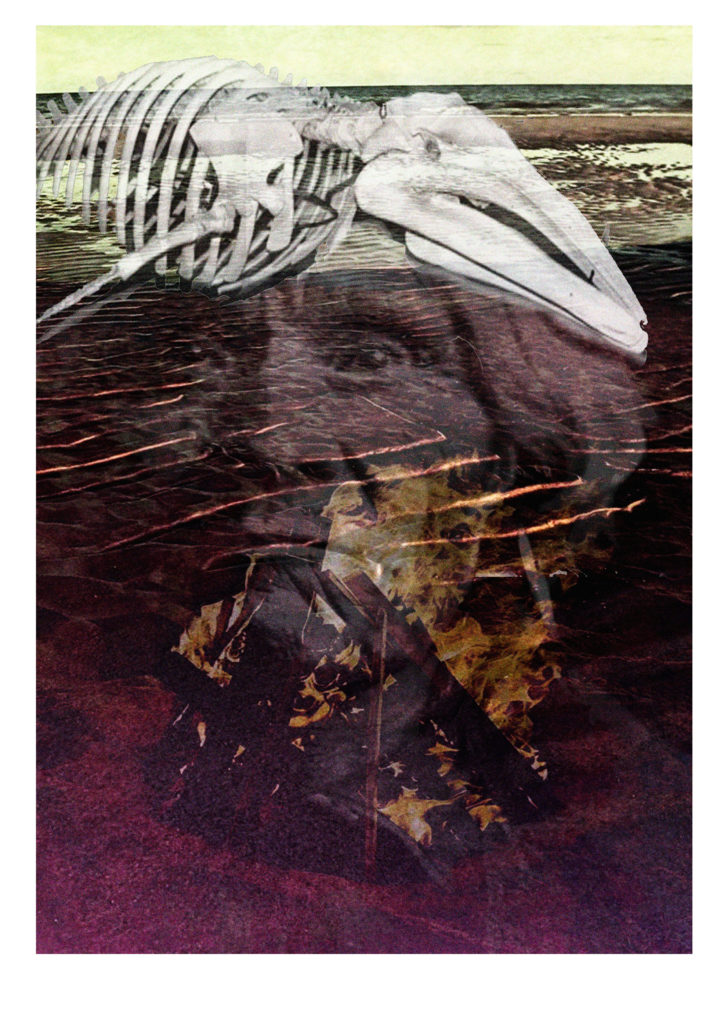

Illustration by Andy Paciorek and Edward Sheriff Curtis

Illustration by Andy Paciorek and Edward Sheriff Curtis

BY A.J. RUTGERS

Part 1

Cal-my-Ish-met-al squatted at low tide on the beach of the Salish Sea, and with his hands he leveled a patch of sand. All night he had sheltered from the rain under the train trestle with a small fire. He now watched as the Canadian Coast Guard hovercraft dragged the young whale into Semiahmoo Bay. The Humpback had died on the beach, strangled in an entanglement of fishing lines and nets.

The whale had beached himself on the Canadian side of the bay, where he succumbed to the inevitable. Many people from the seaside town of White Rock came to the beach to try to rescue him, but it was too late for Y’bo’m.

All day men, women, and children gathered by the carcass. The elders from the Semiahmoo Nation burned sage and performed a drum circle. Children placed flowers on Y’bo’m’s head. Wasps swirled over his flesh. But Cal-my-Ish-met-al kept his distance, waiting for the proper time. He had more important work to do.

Samples of blubber were cut from Y’bo’m before they towed him into the bay. There they slipped the rope from their craft and let the cetacean drift to the ocean floor. Y’bo’m’s body remained enshrouded in fishing lines and nets, and the rope trailed his carcass to the bottom.

Cal-my-Ish-met-al knew he had to act. He would have only one chance when the tide slacked and turned to flood. He sat by the cold June waters of the sea and from the back of his sandy altar he dredged a small canal down to the water. There the flooding tide would start to fill it and surround his magic and carry it to Y’bo’m.

Murmuring an incantation he took his moose hide satchel and shook it. Inside the beaded bag were ancient bones that had been handed down to him from his grandfather. Cal-my-Ish-met-al scattered them over his temporary altar. He lit some sage and leaned into the smoke, giving himself a smudge bath as he pulled the tendrils of smoke onto his chiseled face.

He had only seen this sign once before, when his grandfather told him to commit it to memory.

“If these bones ever show this pattern near the death of a whale,” his grandfather had said, “then you must crush them, and burn them into a fire of sage and seagrasses and return them to the sea, close to the carcass of the whale, with the next flood and ebb.”

Cal-my-Ish-met-al studied the divination, praying he has misread it. But the longer he sat on his haunches and stared at the sculpture on the sand, the more certain he was there had been no mistake. From his belt he slipped the hatchet that he had used to cut the wood for his fire. Then on his altar he placed the large, flat rock he had carried with him from the train tracks. With the blunt end of the hatchet he began crushing the ancient bones. The sage smoke and his sadness for the loss of his lifelong talisman combined to flood his eyes with tears. He began to chant.

At dawn Cal-my-Ish-met-al sat on a polished driftwood log high on the beach. He stared at the flat Salish Sea and the flat grey sky and the flat sandy beach and wondered, what have I unleashed?

Part 2

Donny Holmstead sat in the back of the Grady White and fired another steely into the grey waters of Bute Inlet. It cut into the light chop with a zing and a bloop that you could hear over the hum of the trolling outboard motors. He glanced at Nick, the fishing lodge owner, who was sipping a whiskey soda.

“I’ll take another if you’re pouring,” he said, as he reached down into the white plastic bucket on the floor of the boat and picked up another ball bearing. In his left hand he held a slingshot that extended over his wrist. Stretching the rubber band back behind his ear, he punted another steely high into the air. He followed its arc with his outstretched arm as it fell from the sky.

“Hold up your glass,” said Nick, hoisting a bottle out of the built-in cooler under the bench seat.

Donny reached back and Nick poured, slopping some onto Donny’s fingers. Donny set the glass down and licked his fingers clean, paying special attention to the three Stanley Cup rings on the gnarled digits of his right hand.

“Spillin’ booze is bad fishing luck,” he said with a grin.

“You get those three with the Canadiens?” asked Joe, the lead guide.

Donny stared at his rings and replied, “Yeah, these three with Montreal. These other two”—he gestured with the hand that held the slingshot—”were with Detroit.”

“Seal,” yelled Darrel, the boat’s pilot. He pointed off the port side where a black, bulbous head bobbed some fifty feet from the boat. Donny took dead aim with the weapon and let it fly. The ball bearing thumped into the skull of the seal; blood spurted up like a clam spouting water on a beach. The seal sank below the water.

“He shoots! He scores!” Cheered the men.

The two women that Donny had brought with him both took another sip of their Smirnoff coolers and stared at each other.

“That’s one who won’t steal anymore salmon,” said Nick. Seals were notorious for clamping onto hooked fish.

“Hey Joe, you play hockey?” asked Donny of the fishing guide. Joe was balancing on the gunwale of the craft. His arm was looped around a wire stay while his eyes scanned the four fishing rod tips looking for any sign of action.

“Just some pickup in the off season.”

“Well, never play with a damn ring on. Once I went to glove a slap shot and that puck crumpled my wedding ring into my finger. They had to cut that mangled band off my swollen finger with the skate sharpener at the rink. I finished the third period though, with a goal. Never worn a ring playing again. And I’ve been married three times.” He winked at the two beauties as they curled up in the cushioned seats at the aft of the boat.

“Look, look,” said Joe, pointing to one of the rods that started flattening from its hard bend. “We’re getting some action. Once it goes slack I’ll grab it, set the hook, and then hand it to you, Mr. Holmstead.”

“Screw that,” said Donny. “This ain’t my first rodeo. I can set my own hook.”

“No problem,” said Joe backing away, his hands in the air, still smiling. He knew how to handle legends like Donny Holmstead.

Then the back port-side rod slacked straight. Donny lunged at it and wrestled the rod from the holder, jerking it back hard and reeling as fast as he could. He pulled again but it was obvious nothing was there. He had missed the hit. Now the starboard rod went slack and Darrel yelled from the flying bridge.

“Fish on!”

Joe grabbed the rod and jerked it hard once, reeled three times fast, then jerked the rod again. The line started to sing and the rod bent down hard.

“Got him,” said Joe, as he adjusted the tension on the reel. “Here you go Donny.”

Donny began working the fish as Darrel brought the boat to a stop. The three men—Nick, Joe, and Darrel—jerked up the other rods to dislodge them from their down-riggers and started reeling them in. They were well rehearsed. Donny kept working his fish.

“Feels like a big one.”

The three experienced fishermen said nothing.

In the wake a silver fish rolled on its side and drifted to the boat.

“It’s a beauty!” yelled Joe. Donny moved to the gunwale to get a look. “Keep your tip up. She’s gonna run.”

Donny lifted the rod as the salmon, spooked by the hull of the boat, jolted back to life and surged back into the depths. The reel screamed. Donny held the rod high, the tip pulsating in the afternoon sun, spray slinging off the line.

“Whoowee!” he shouted.

The line slowed and Donny began wrestling his prize back to the boat. Darrel bumped the throttle to edge the Grady White around so the line was playing out from the side. Everyone focused on the water.

“There it is,” one of the girls squealed. Just as she spoke, the fish jumped and danced on its tail, it’s head thrashing and the orange lure dangling near its jaw.

“Bet she’s twenty pounds,” said Nick.

“Twenty-five,” said Darrel as he lit another smoke.

Donny grunted as he hauled back up on the rod. He was beginning to sweat.

The salmon now bobbed to the surface, it’s snout poking above the water. The exhausted creature came to the side of the boat.

Joe shoved a net deep into the water. As the net came up the fish jumped again and did a headstand. Normally Joe would have backed off and let the prize dive deep under the boat, but since this was the first fish for Donny, he lunged deep and scooped the salmon into the net. A moment later, the fish hit the deck flopping.

Everyone cheered and shook Donny’s hand.

“Congratulations. Nice fish.”

“Pour me a drink,” said Donny, lifting his baseball cap to wipe a hand over his his bald dome, with its rim of scraggy blond hair.

Hoisting glasses, everyone toasted their success—all of them except Darrel, who studied his watch and surveyed the waters of Bute Inlet.

“We should be heading back.”

“Back? Hell no. The fish are just starting to hit,” said Donny.

“Well, you do have your presentation to do for the King Drug’s staff back at the lodge,” said Nick.

“Oh that. I’m not worried. They paid me already. So they can wait. Besides all I gotta do is jump on one of Vigor-fit’s exercise machines. They just want me to wow the store managers with my celebrity. Let’s keep fishing. We can be late. What’s our daily limit?”

“Two,” said Joe.

“All right, let’s get one more. Then you boys can take me out again tomorrow.”

“Okay, your call,” said Nick. “But we can’t take you out tomorrow. The Grady’s booked. You’ll be fishing with one of the guides in the Boston Whalers. It’s a different experience; you’re closer to the elements.”

“Who’s your best guide?”

“Depends what you want,” said Joe, as he took a small wooden bat and thumped the salmon hard on the forehead. The Chinook jerked and flopped in the net, a small wound spilling blood onto the white anti-slip deck.

“Let’s get a photo,” said Joe. He handed the prize to Donny, who held it across his chest. The two women came to stand on either side of him, and Nick snapped some pictures.

“Both of the guides who could take you are pretty good,” Joe continued. “But it’s their personalities that you want to pay attention to. You’ll be out on the water with them for twelve hours.” He grabbed the salmon back from Donny and slipped it into the cold saltwater catch hold.

“There’s Pacific Willy, who’s a tree hugger type. Very meticulous, well organized, quiet guy who communes with nature. He has a real feel for where the fish are. Treats his catch with reverence. Then there’s Shoeless Sean. Never seen anything like him. Goes barefoot year-round. He’s a crazy bastard. Takes chances, but gets fish. Has a quirk though—he hates mud sharks. So if he catches one, he takes ’em and flips his trolling motor up and feeds it into the prop. Chews them into bloody bits and pieces, pretty crude.”

“I’ll take him,” said Donny. “I like crazy.”

With the rods set, the Grady White settled back into trolling. Donny and Nick poured more whiskey. Joe grabbed a bucket, leaned over the edge of the boat, and filled it with salt water. He sloshed the water onto the deck to wash the stringy fish blood down the floor drain. The smell of fish, motor exhaust, and blood filled the cockpit. The Grady turned into the sun and trolled back towards Sonora Island.

Part 3

Down on the silted bottom of Semiahmoo Bay lay Y’bo’m. Strewn along either side of him were round, algae-matted crab traps, torn from their marker buoys by storms, their ropes now twisted around Y’bo’m’s black, barnacle-encrusted corpse. Inside the traps lay pale, dead crabs. In a cruel twist of fate, each trap also held a few live red crabs that had crawled in to feed on the dead ones. Once they realized their error, they poked the tips of their claws through the netting and clung to Y’bo’m, pulling at his flesh in a vain attempt to escape.

As the rising full moon penetrated the murk, a stirring began. The crabs dug harder into the whale. Y’bo’m’s black skin began to shimmer and change color. The barnacles on his back started to glow, and the dead crabs awoke in new eerie white shells. Y’bo’m began to move. His mighty tail shook and the towrope lashed the bottom of the bay like a sea serpent, kicking up plumes of mud. His large eyes flickered and, glowing red, opened.

The great creature twisted and tensed. Then, rising from the bottom, Y’bo’m thrashed his tail and pulled his pectoral fins to his body. Up he rose, and with one great convulsion broke through the surface. He was glowing white. The crab traps clung to him draining muddy water, and the white nylon lines and mesh trailed him like jewelry. He crested out of the sea and broached on his side—water, shrimp, and mussels spewing from his blowholes. He was moving. He had become Y’bo’m K’ic’d. He was possessed.

Out into the Salish Sea he surged, awakening to his new consciousness. He broached the surface and rediscovered his strength.

Into the Strait of Juan de Fuca plunged Y’bo’m K’ic’d. He bashed the rusted hulls of freighters that plied coal from Roberts Bank to the power plants of China. North he moved—up the Strait of Georgia—his mind beginning to focus on one all-consuming thought.

Revenge.

Revenge on those who had starved him. Revenge on those who had cut short his youthful life. Revenge on those who had robbed him of his soul. It was on these evil creatures that he would wreak his vengeance. The twirlers of lures, the twisters of hooked herrings, the dispersers of nylon mesh, these he would destroy.

Y’bo’m K’ic’d was in a rage. North he swam to the Discovery Islands. North to the Johnston Pass. North to the fishing grounds of Bute Inlet. Pity all those in his path, for Y’bo’m K’ic’d was unleashed.

Part 4

Donny stood on the dock in his red, full-body Mustang floatation suit, the zipper pulled up to his waist. His barrel chest prevented the jacket from cinching all the way up. For warmth he wore his new Tyee sweatshirt. The fishing lodge had given it to him because his salmon tipped the magical thirty-pound mark. That was rigged. They had shoved some fishing weights down the Chinook’s throat before they weighed it. Nick wanted a photo for his celebrity wall.

Behind Stuart Island, the sky was glowing with the rising sun. In another hour it would crest the island’s mountaintops and bathe the fishing lodge in warmth. Donny stared at the flotilla of Boston whalers that were skimming across the inlet. They were coming to gather the sport fishermen—the staff of King Drugs—who were congregating on the dock. The lodge supplied them with coolers and thermos bags full of lunches and snacks. Cookies, chocolate bars, apples and oranges—but no bananas, as the guides considered them bad luck.

Donny stood alone, avoiding eye contact with anyone, not wishing to talk. He was hungover. Instead, he stared at the overlapping orange and purple starfish. They were cemented on the rocky ocean floor, almost fluorescent in the tidal stream. Around them carpets of seagrass blossomed and swirled like anemones. Now flowing south, though later with the changing tides they would turn north. Donny searched the faces of the incoming guides, trying to guess which one was Shoeless Sean. He picked him out right away: the cocky young kid who came in a bit faster than anyone else. He was standing in the back of his Boston Whaler.

“Mornin’ Mr. Holmstead. Welcome aboard.”

Donny went to load his cooler and thermos bag, but Sean interrupted him.

“You just step on board sir,” he said. “Let the attendant hand me those. No use in us losing our lunch and beverages to the salt chuck when we have such fine looking attendants to help.” He winked at the cute blonde who had secured his stern line. She was now holding the bow tight to the dock so Donny could board. Donny had no problem with that; he was feeling a bit unsteady on his feet anyway.

Donny lowered his frame into the vinyl fishing chair and faced his young guide. Sean kept his banter going with the attendant as she handed him the thermos bag and cooler. As soon as the cargo was secure Sean unhitched the stern line from the dock cleat and nodded to the blonde, who then pushed off the bow. Once they were clear, he gunned it. The wake of the boat jostled the other Boston Whalers at the dock and everyone yelled at the young punk. Sean laughed and swiped back his greasy, long hair as he booted it south.

“I see ya already got yourself a big one,” he yelled over the roar of the motor, gesturing at Donny’s sweatshirt.

“Yeah, just barely,” replied Donny. The wind in the speeding boat flapped the hood of his survival jacket over the back of his head. In the damp morning air Donny wished he had stayed in bed with his lovelies rather than being out here in the cold.

“Wanna coffee?”

“You got any whiskey for it?”

“I’m sure the lodge packed some for you,” said Sean, as he throttled back on the motor to rummage through the insulated bag.

A few minutes later they were skimming over the rippled waters of the Yuculta Rapids, each sipping a “Poor Man’s Irish.” Donny began to cheer up.

“Where’re we heading?”

“Well the tide’s pretty slack at the moment. So we’re going to poke our nose into Hole in the Wall. With luck there are some Chinook feeding on the schools of herring trapped in the whirlpools. We can’t stay long in there; once the tide turns that place is as crazy as any whitewater river in the world. Only worse, because them whirlpools suck down deadheads that will puncture any boat. This little Whaler wouldn’t stand a chance. We’d get sucked right down ’em, never to be seen again.”

“Sounds exciting.”

“Sure is,” said Sean, as he put on the sunglasses that were dangling around his neck. “And magnificent!”

The Whaler throttled back at the entrance to the pass.

“We’ll prep our bait here, in calm waters. I see a few guys have beat us here.”

Donny twisted around in his chair. To the west he could make out twelve or so fishing skiffs circling in the passageway.

From the side gunwales Sean pulled out two rods. They were already rigged with musket-ball-sized weights and hooks. He settled the rods into the holders and pulled enough line out so the weights rolled around at his bare feet. Reaching behind him he pulled out a small cutting board and from his vest pocket he produced a file. This was all part of the show.

“Ya gotta have sharp hooks. Salmon don’t see very well and they’ll graze up on your bait a few times before they hit. So when they do, you wanna make sure your hooks bite.” He grinned at Donny and filed the hooks on each line with short rapid strokes. Then he opened the bait well beside him and plunged his hand into the cold water. Trapping a herring in his lightly clenched fist, he placed the fish on the cutting board. Pinching it hard in the spine behind its head, he continued talking.

“We’ll just put one hook in for the time being. Later when we’re trolling I’ll use cut bait and then we’ll use two hooks. But for now I want this little fella swimming in distress. That’s what attracts the salmon.”

Soon he had both rods baited. Balancing the cutting board and bait on his lap, he throttled up his motor and entered Hole in the Wall.

The passageway was awe-inspiring, narrowing at first then widening. On the north side were the cliffs of Sonora Island and on the south the rising mountains of Maurelle Island. The waters were churning. Slow, giant, twisting whirlpools moved between the beds of kelp. Gulls and eagles screamed from the cliffs and seals lay on the rocks.

Sean maneuvered his boat into the current of one of the whirlpools. They joined a carousel of other boats circling the eddy.

“Okay,” he said. “Grab that rod and I’ll throw the bait in.”

Donny did as he was instructed. Sean dropped the musket ball in the water and then lobed the squirming herring overboard. Peering over the side, he made sure the bait had the right action.

“All right, pull the line out about twenty-five pulls.”

Donny pulled, the reel clicked. The musket ball swept down into the vortex, pulling its wounded cargo with it.

“Do the same to the other one.” said Sean. He now focused on the other boats. The mangle of fishing lines converged into the center of the whirlpool.

“Don’t they ever get tangled?”

“Sometimes, but if they do I’ll cut em loose, and we’ll bugger off and troll up the other side of Stuart in the sun. For now we’ll fish here.”

Round and round the whirlpool they went. Donny began to feel sick.

“Ya know what,” he said. “That sunshine is sounding pretty good. How about we pull up lines and head there?”

“You’re the boss,” Sean said, and he steered the boat out of the current and started winding in a line. Donny worked the other. When the bait appeared Sean grabbed the line and swung it hard, whipping it around his fingers. With a clean jerk the herring flipped into the water.

“One for the fishing gods.”

They fired up and headed for the calm waters.

The afternoon sun was beating down. Donny had removed his survival suit and Tyee sweatshirt. His burly white chest was turning pink in the first rays of a delayed summer. The two fishermen were puttering down the coastline with two rods bent over the side. Each was nursing a cold can of beer.

Donny lifted an eyebrow as a seal surfaced behind them.

“You got any slingshots?”

Sean beamed. “I got two,” he said. He pulled out a tarnished bucket. “Not everyone is into busting seals.”

Donny loaded and thwacked one off.

“Missed.”

“I bet you’d like gull kiting,” said Sean.

“What’s that?”

“We used to do it on the seiners. We’d bait herring and hook gulls. Then as they flew away we’d tow ’em with the line like a kite. You could reel them in or let them fly high. When you got bored you’d jerk the hook out. It would pull their guts out and kill em. But who cared. It was funny.”

Donny laughed and took a pull on his beer.

“So tell me Sean, what’s the biggest salmon you ever caught?”

“Forty-five pounder. Last fall. It was close to where we are. Had a lady on board—Carol-Anne something. Well, we fought that fish for over two hours. She was great. Bet she sweated off ten pounds in that fight.”

“Wow, I’d sure like to catch something like that. Wonder what the biggest one ever caught was.”

“Oh, it was a ninety-three pounder up in Alaska on a rod and reel. Commercial guys have gotten bigger—around a hundred and twenty pounds. Couldn’t imagine catching somethin’ like that. It’d be awesome.”

“Well there doesn’t seem to be anything here.”

“Don’t sweat it,” said Sean. “The tide is turning. They’ll ride in with the schools of bait on the flood. I’ll turn on the radio and see if there’s any chatter from the other guys.” He reached down and turned on the small marine-band radio bolted under his seat. Some garbled voices cackled to life. Sean listened for a few moments, his ear tuning to the speech. Donny couldn’t understand a goddamn thing they were saying.

“Jesus. Everyone’s still talkin’ about it.”

“What?”

“Ah, strange shit. Started last night in the Gulf islands. A long-line fisherman had all his lines stripped clean from his boat. I mean every single one. That stuff is like piano wire. Whatever he snagged it on, it ripped it clean off his gear. Then farther north a seiner had his nets shredded. Never heard of such a thing. And this morning the talk was a big commercial trawler got his nets demolished.”

“What do ya think it is?”

“Don’t know. Submarines maybe. The Americans are always prowling these waters. Maybe a flotilla of them on exercise. They won’t bug us though. They’d travel up Discovery passage for Johnston Strait.”

“That’s good,” said Donny. “Want another beer?”

“Ooh!” cried Sean, stiffening in his seat as the starboard rod suddenly went slack. “We got a hit.”

Donny dropped his can and snagged the rod. The foam from the beer spewed out on the bottom of the boat, mixing with the bilge water. He jerked hard, reeled and then jerked hard again.

“Nothing.”

“No, no. Keep reeling. Fast.”

Donny started turning hard, and after a few seconds he felt it. He jerked the rod again and it took off. The line streamed out of the reel.

“Jesus Christ!” yelled Sean. “Have you got a seal?”

The line slowed and Donny started the rhythm—pulling up and reeling down.

Five, ten minutes he pulled and reeled. Then off the stern something rolled and flashed silver in the water.

“There she is. It’s a giant,” said Sean as a silver tail flopped for a second on the crest of the wake.

The game was on. Sean reeled in the other rod and stowed it.

Donny’s reel was chattering out more line. Ten minutes later he was still reeling.

“I don’t think he knows he’s hooked,” said Sean.

“I’d just like to see him. Make sure it’s not a seal.”

“Oh it’s not a seal. I saw it. It’s a fish all right. Maybe a halibut, but they’re pretty rare in these parts.”

An hour they fought and wrestled, reeling in, only to have the line play out again. Donny’s chest dripped streams of sweat. Then the line went slack.

“I think I lost him.”

“No keep reeling. He’s turned towards us,” said Sean, revving the engine to get tension back in the line. Then through the churn it appeared. It was a salmon. A big one. The biggest one Sean had ever seen. His voice blasted with excitement.

“Holy Cow. It’s a monster. And you’ve snagged him in the side. That’s why he’s so hard. You can’t turn him.” Sean leaned into Donny and grabbed his knee, his hand vibrating. “This is gonna take a lotta skill. Ya can’t bully him. You’ll have to play him out.”

Two hours later they were still working the rod. The fish had towed them back towards the entrance to Hole in the Wall. They were no longer in the sunshine; the mountains of Maurelle Island now cast them in shade. It would not be dark for many hours here in the North Country in mid-June, but in the mountain shadows a chill crept back into the air. Donny didn’t feel it. He just kept reeling.

Sean looked nervously at the passage entrance and feathered the prop to keep the line taut. He didn’t dare try to drag the catch too hard. He prayed it would tire. They couldn’t go back into Hole in the Wall, not with the tide running. White water gushed from the pass. Where they had baited the hooks that morning, the water now boiled in six-foot chops that held no rhythm, just chaos.

Come on fish, he thought. Give up.

As if by command, Donny suddenly found it easier to pull the rod up.

“I think we’re winning.” He announced.

Sean grabbed his net. “I hope he fits.”

Donny grinned back at him.

The fish surfaced, its nose and fin breaking the chop. The hook was lodged in the flesh just in front of its dorsal fin. Donny gently lifted and reeled down. The fish gyrated and squirmed away from the boat, running on the surface and looking like it was going up a river. Sean throttled the motor and pulled him back. They were getting close.

He glanced at the pass; logs from the spring runoff were shooting into the bay. Then from the froth something gushed. Something was thrashing through the foam. Y’bo’m K’ic’d had arrived.

Part 5

The rain pattered on the trailer roof like metal brushes on a snare-drum. Farther back on the other side of the kitchen large droplets spilled from the cedar boughs and plunked onto the tarp that patched the roof above the bedroom, providing the tempo bass.

In the living room Cal-my-Ish-met-al sat in meditation. Beside him crackled a cedar fire in his scavenged cast-iron stove. Surrounding him were shelves of mason jars full of herbs, minerals, and dried animal parts. In the windows hung dream catchers. And from a place of honor on the wall glared a wooden mask with two eagle feathers drooping over hollowed black eye holes. The mask was trimmed at the top with horse’s tail hair that cascaded down and framed it in grey and black. At the bottom a red-painted mouth screamed out.

Through the din of the November rain, Cal-my-Ish-met-al heard a metallic rap on the aluminum door. He rose, his knees cracking. He had aged in the six months since he had sacrificed his talisman.

He opened the door and before him stood a man in bare feet. He wore a red coat that was slick from the rain, the long sleeves pulled down past his hands. From below a drenched baseball cap a voice asked, “You the shaman?”

Cal-my-Ish-met-al closed his drooping eyelids and nodded. Stepping back he allowed the man in.

“I will make some tea,” he said. And he turned to his kitchen.

The man stepped up into the musky trailer and seated himself on the worn couch. He did not remove his hat or jacket.

Cal-my-Ish-met-al plugged in the kettle and threw two teabags into his teapot.

“Why do you seek me?”

“I’m told you know about incantations and evil beings.”

Cal-my-Ish-met-al took a jar from his shelf and grabbed a twist of the dried abdomens of yellow jackets. He tossed them into the teapot. He knew it would be a long night.

“I have some knowledge.”

“Then let me tell you a tale,” said the man.

Shuffling in his kitchen, Cal-my-Ish-met-al assembled mugs, honey, and milk on a tray. Finally he poured the boiling water into the teapot, placed it on the tray, and carried it to the coffee table. Bending down he grabbed some split wood and poked the pieces into the stove. His grey hair fell over his brow as he stirred the embers. By then, the stranger was already deep into his story.

“We had that Chinook right up against the boat, half in the net, and water sloshing everywhere. Then something thumped us from behind. We turned and the beast was upon us.” He paused while Cal-my-Ish-met-al settled himself into a stuffed chair.

“I tell ya I never seen anything like it. It was white, with red eyes, and all over it was a veil of debris: hooks, metal, and crab traps. It was fearsome.”

Cal-my-Ish-met-al poured some tea, the aroma wafting through the room.

“The handle of the net that salmon was in somehow got twisted into the gunwales. We were stuck with a huge chinook thrashing in the water beside us. But now we had to face that beast. We gunned the motor, but it was faster, rising up on the stern of the boat. So we pivoted the motor up outta the water, the propeller slicing at the monster like a weed whacker. Chunks of flesh or something flying into the air.”

Cal-my-Ish-met-al blew on his tea, and a wasp abdomen spun on the surface. He took a sip. The man continued.

“That devil slipped back into the water, then raged at us again. He broached out and towered above us, pivoting in the air. I tell ya I saw his blowholes. I stared right down his mouth. Right down his baleen. It was like a venetian blind of razor blades. I just started punching. That was the last thing I remember.”

“What do you want of me?”

“I came to in the hospital in Campbell River. I told them my story but no one believed me. They said we were swallowed by a whirlpool. Knocked silly by deadheads. But I know what I saw.” He bent his head. “I was the only one to survive. You have to tell me if such a thing could exist.”

Cal-my-Ish-met-al took another sip of his tea. “I know of your demon,” he said. “They call him Y’bo’m K’ic’d. He is not evil. But he was too young. It was my mistake.”

“Your mistake?”

“Yes. It was I who summoned back his soul. I did not learn until later that the young ones are not suited for this task. It was my error.”

“Then you understand him.”

“Yes, I suppose I do. More than any other human being.”

“Then you can help me hunt him.”

“Hunt him? Why would you want to hunt him?”

“So I can kill him,” he said, reaching for his tea, the sleeves on his coat sliding back and exposing his hands. On his left, just a thumb and pinky finger remained. On his right, a metal hook.

“And gut him. And get my rings back,” said Donny.

A.J. Rutgers is from White Rock, British Columbia, and has been a fiction writer for two decades. He won a Flash Writing contest for his story, “Farming,” and for his story, “The Loon Spirit Totem,” he placed second in a Short Fiction writing contest in the on-line community “Becoming a Writer.” He’s currently at work on a novel titled Mule. Noting that Bob Dylan, in his acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize in Literature, spoke about the impact Herman Melville’s Moby Dick had on his writing career, Rutgers says he intended “The Salish Sea Zombie” as “a humble salute to Bob Dylan and as an homage to Herman Melville.” He adds, “As a fun aside I have included a homophone of a phrase and a palindrome that references Moby Dick. I hope the skilled reader will appreciate the puzzle.”

A.J. Rutgers is from White Rock, British Columbia, and has been a fiction writer for two decades. He won a Flash Writing contest for his story, “Farming,” and for his story, “The Loon Spirit Totem,” he placed second in a Short Fiction writing contest in the on-line community “Becoming a Writer.” He’s currently at work on a novel titled Mule. Noting that Bob Dylan, in his acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize in Literature, spoke about the impact Herman Melville’s Moby Dick had on his writing career, Rutgers says he intended “The Salish Sea Zombie” as “a humble salute to Bob Dylan and as an homage to Herman Melville.” He adds, “As a fun aside I have included a homophone of a phrase and a palindrome that references Moby Dick. I hope the skilled reader will appreciate the puzzle.”