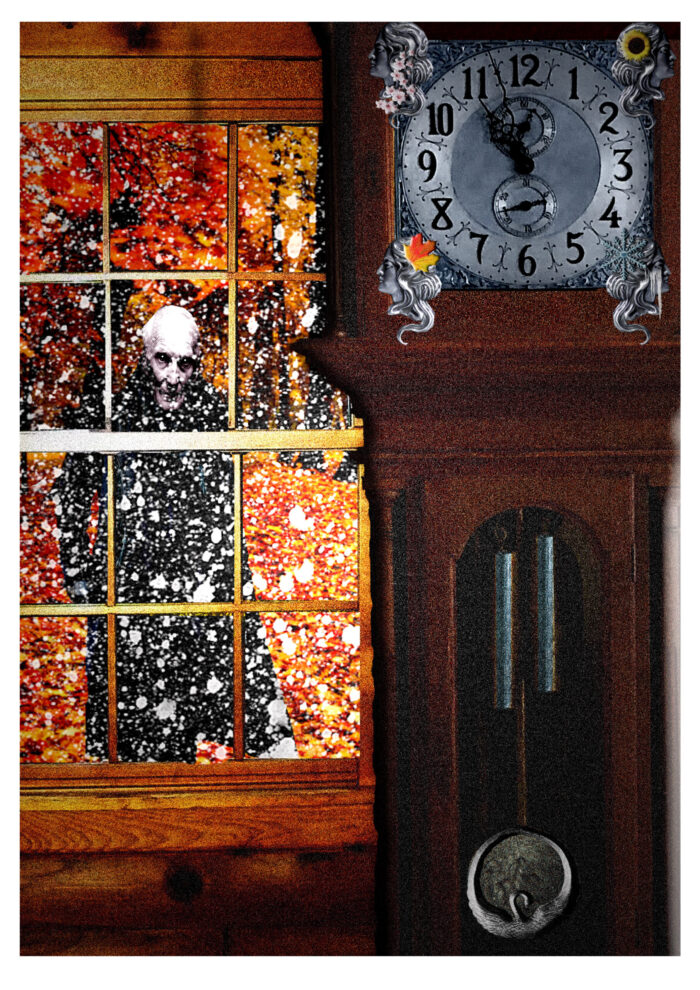

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

HONORABLE MENTION, SPRING 2022

THE GHOST STORY SUPERNATURAL FICTION AWARD

BY GOLDIE GOLDBLOOM

For Mendel Goldbloom

At the end of the week, the Keeper of the Hours donned his long black coat and his long black scarf, and he took up his cane and shambled his way through the village. He was a big man, and though he wished his limbs were capable of more dignity, they were not. It was raining, but also snowing, and the golden leaves were falling from the trees. The muddy streets were paved in slippery gold.

He kept the Hours next to his heart, in his breast pocket. His old and spotted hand was raised, again and again, to pat the pocket, to reassure himself. The children of the village, bundled in shawls, watched him from behind the painted picket fences. They sucked their thumbs. Their eyes were big. The Keeper’s solemnity terrifying. The striking of his cane against the stones of the road, the tolling of a great bell, the ticking of the rain as it shattered against the leafless trees. The children, afraid, did not call out. They did not even whisper. They floated along behind the Keeper, flitting between the ravaged gardens.

The sole mourner, a middle-aged woman, was shouted at by the men who had been praying in her empty rooms. “Get up! Arise! Go forth and live again!” She walked around the outside of her small wooden house in rain that was also snow, pushing her way through the sodden goldenrod and the rotting phlox, the naked branches of the maples shaken by her passing.

After she came back inside, and after a brass nail had been hammered into the floor where she had been sitting, the Keeper knocked and entered solemnly, bowing his head. “I am here,” he said, “to restore the Hours.” And according to custom, he bent his head and placed his hand on his heart, where he could feel, beneath the fabric, the Hours.

The woman nodded, once, and turned her back on him, for mourners never wanted the Hours restored. The Keeper had been told that there were three clocks in this home, one in the bedroom, one in the tiny room where the woman ate her meals and one, the largest, in the room where she had mourned. He frowned at the woman’s back and went to the bedroom.

Everything was in disorder. Papers were spread out on the floor. A ball of yarn ran underneath the bed. Blue chicken feathers hung in ribbons from the ceiling and twirled in the icy wind that came through the open window. On the bureau was a small brass clock, lying on its side, face down. The Keeper lifted this clock and cradled it in his palm for a moment. Perhaps it had never worked? It smelled, faintly, of the woman’s skin, of bread, of soup, of the snow that was falling outside and of something else that he could not name. It had a simple key on the back and he wound it until he felt the spring tighten and heard the ticking begin. And then he removed the Hours from his breast pocket, clicked opened the silver case and set the time.

In the kitchen, there was a clock with a painted tin swan that rocked back and forth. The Keeper unlocked the wooden cabinet so he could observe the rise of the lead weights as he wound the key. This clock was three hundred years old and the mainspring was easy to over wind. The twin weights rose up inside the cabinet, like dark angels, heavy, misshapen, not meant to be seen. Each time the curved brass minute hand passed the number twelve, a small bell inside the hood was struck, and it rang, once, twice, thrice, in a shrill voice. The ticking of this clock filled the room and spilled into the next, where the woman still stood.

In his grave fashion, the Keeper approached the great clock that stood, alone, in the main room. It was over six feet tall, slender, made from a single tree that had been carved twenty-four years earlier. It was beautifully proportioned, with wide shoulders and a narrow waist, and the woman had polished it lovingly every year it had stood in her house. The face had, at each corner, a painting of a woman; the Spring woman, the Summer woman, the Autumn woman and the Winter one, covered in ice.

He did not call out to the mourner, but he could feel, emanating from her, the deepest dislike. She would not turn around even as he approached the largest of her clocks. She stood at the window, and beyond her, the chartreuse leaves of the magnolia that had not yet blackened and fallen, stood out, electric, against the grey sky. In the Keeper’s pocket, the Hours purred along, unstoppable. Against his chest, this beating thing.

“Well, then,” he said softly. “Come now.” For according to custom, she must stand next to him as he restored the Hours on even this clock. But she did not come to him. “Lady,” he said. “Please.” And still she did not come but stood at the window, watching the endlessness of the rain and the snow and the sky and everything that was beyond her.

So the Keeper was forced to go to her and to bind her with his long black scarf and to draw her slowly back with him to the clock and there, he placed in her hand the great key, shaped like an S. It was not his job, after all, to restore the Hours to this clock, but hers.

She did not want to wind the clock, but he was the Keeper of the Hours and in this broken world, the Hours do not stop. In silence, the Keeper willed her to lift her hand. In silence, she raged. They did not look at each other. Outside, the children massed at the fence, craning their necks, watching. From the bedroom, from the kitchen, clicks, the sound of gears, the two clocks preparing to chime. “Lady,” said the Keeper. “It is time.”

She, who felt made of something impossibly unyielding, raised the key and pushed it into the first of the brass-lined holes, and within the huge casket of the clock the spring turned around the key, resisting it, resistance built into the metal from the moment of its conception. The woman turned the key more and more slowly until it could no longer be turned. Then she withdrew the key and reinserted it into the second brass-lined hole. The dark and weighty angels rose up into heart of the clock one by one. The children, obscured in the snow, almost transparent in their coldness, pressed their faces to the fence. The snow fell and fell.

The clock, too, waited. It was fully wound. The woman rested her head on the gleaming wood. After a moment that did not seem to pass, she reached out and barely touched the pendulum, and it swung, first to the left, and then to the right, the first of many seconds, and minutes, and hours, away from when this great and beautiful thing had lain unmoving and silent in her home.

___________________________________________________________

Originally from Australia, Goldie Goldbloom is an internationally published writer of fiction and nonfiction. She is the recipient of fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the City of Chicago, the Brown Foundation, and Yaddo. Last year, her novel, On Division, won the French Bookseller’s Prize for Fiction and the National Jewish Library Award. Previously, her novel, The Paperbark Shoe, was placed on the NEA Big Reads list and won many awards, including the AWP prize. Her writing has appeared in Ploughshares, the Kenyon Review, Le Monde. and on NPR. She is a single mother of eight and an LGBTQ advocate.

Originally from Australia, Goldie Goldbloom is an internationally published writer of fiction and nonfiction. She is the recipient of fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, the City of Chicago, the Brown Foundation, and Yaddo. Last year, her novel, On Division, won the French Bookseller’s Prize for Fiction and the National Jewish Library Award. Previously, her novel, The Paperbark Shoe, was placed on the NEA Big Reads list and won many awards, including the AWP prize. Her writing has appeared in Ploughshares, the Kenyon Review, Le Monde. and on NPR. She is a single mother of eight and an LGBTQ advocate.