WINNER, SUMMER 2018

The Ghost Story Supernatural Fiction Award

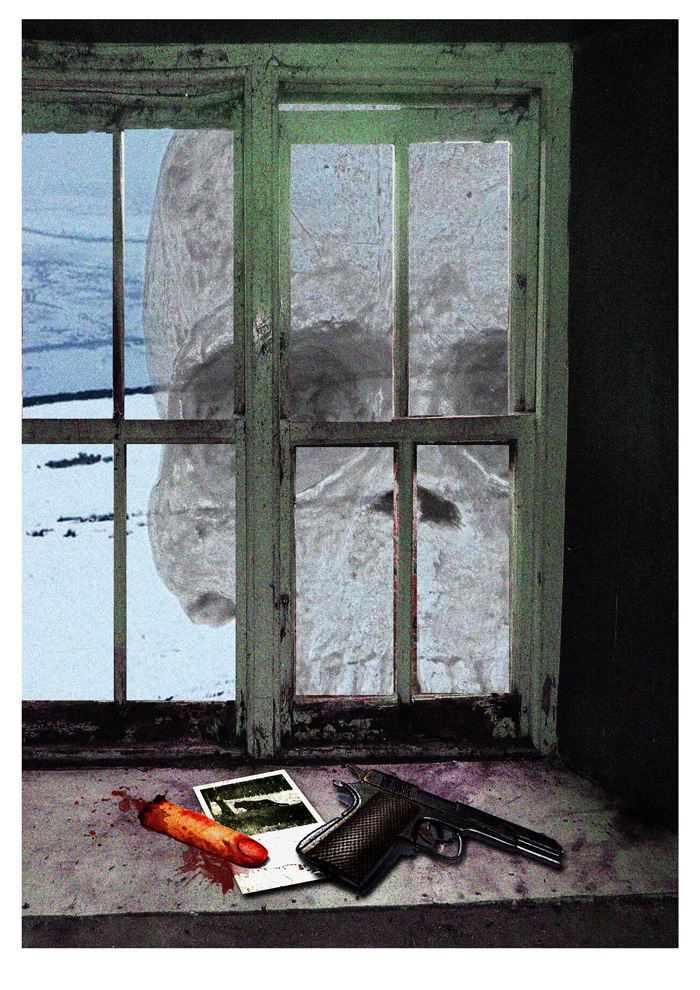

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

BY ROWAN BOWMAN

It was early last New Year, the day after my thirtieth birthday. I had been driving from my parent’s farm in Weardale and had taken the scenic route home in the moonlight, following the thin strip of tarmac that winds across the hills. There was no other traffic although it wasn’t yet ten. The moonlight was so bright that there was a dim blue-green smudge of colour to the short-cropped turf, and the heather stood out black against it. I once ran a sheep over and I am always cautious on unfenced roads. I was nearly home, doing well under sixty on the long descent from the moors into the deep, sheltered valley. In the far distance I caught the first glimpse of the Derwent Reservoir, silver in the moonlight. A poacher’s moon.

Stone cold sober, doing fifty, watching out for livestock, yet I didn’t stand a chance. I came round the bend and there was a huge cat standing in the road, the size of a Labrador, maybe a little bigger, jet black, its eyes yellow in my lights. As I slammed on the brakes I instinctively steered away from the creature. There is no room for mistakes on a road that narrow; one front wheel hit the ditch and the car was flipped over onto its roof.

I was shaking, but couldn’t feel any immediate pain. There was a strong smell of petrol. I fumbled at my seat belt, which had jammed. My jacket had fallen from the back seat onto the roof of the car. I pulled it towards me and groped for the pocket knife I keep in it. I sawed through the belt and tumbled out of the door, dragging my coat out after me. The knife clattered down somewhere underneath the car. The airbag belatedly detonated with a dull thump. I reached in past it and turned the motor off. I scrambled up the opposite verge, put my jacket on, and waited in the headlights for the adrenaline to wear off.

I had crashed just where the moors give way to enclosures. The animal I had narrowly missed was nowhere to be seen. The road was flanked by dilapidated dry stone walls with poles leaning against them to support a single strand of barbed wire. Every barb had wool caught on it from wayward sheep evading captivity. I tried my mobile but I knew already there was no reception up here. I guessed I was three miles at most from Blanchland, and began my trudge down the steep road.

About a quarter of a mile later I realised I was in a bad way. The shock numbed my ankles and I couldn’t trust my feet not to stumble. Blood thundered in my right ear, my ribs hurt badly and the cold night air seemed to pierce my lungs with every breath. I decided to turn in at the next farm track I came to and ask for help.

Even so, I almost didn’t go down to Snow Fell Hall. The grand-sounding name belied the shabby farmhouse, a steading at the bottom of a steep unmade track with a loud stream behind it and a windbreak of tall larch. The place had rumours, half-forgotten, muddled stories attached to it and I’d heard it said that many years ago the bodies of two lovers were found downstream, a suicide pact. It was certainly lonely, but it had something about it, maybe the proportions, I don’t know. It seemed to grow out of the hillside. It had two floors at the front but the stone slates sloped steeply down to a single story at the back. Soil had built up behind the cluster of outbuildings that formed the little cobbled yard in front of the house so they were almost hidden from the road. All that could be seen was the moss that obliterated the roof. I thought the place had been empty for decades. I’d nosed around the outside once or twice on summer walks, and I had once even made enquiries about buying it, but the agents who let the land had been unhelpful and vague and I had given up. Now in my moment of need cheerful yellow lights beckoned me.

The door seemed newly painted. Someone with more persistence than I had obviously persuaded the owners to sell. There was no answer at first. I could smell wood smoke, and there had been voices before I knocked. I tried again. The door was opened a crack on a security chain.

“Richard?” a young man’s voiced asked. He sounded relieved.

“No. I’m Jonathon. Jonathon Hedley. I live over at Edmondbyers. I’ve crashed my car.”

He opened the door wide and stared at me. He was around my height, but slim, probably still in his twenties. He had an ugly goatee beard and his hair was a startling black against his white face. He was smoking a joint, which he did not bother to hide. He did not show any sympathy.

“I wondered if I could use your phone. . . .” I let it drift. What I really wanted was to sit down in a comfy chair in front of a warm fire and go to sleep.

“You’d better come in,” he said as if he’d read the lines somewhere.

“Thank you.”

The hallway was narrow, papered in hideous yellow and brown hexagons and lit by a naked bulb. A flight of stairs led up into darkness. The floor was bare concrete with a plastic woven runner up the middle. I followed him to the end of the passage. He pushed open a door and let me go first into a dingy kitchen. It was large and fuggy rather than warm, with a duck-egg blue Rayburn in the old fireplace. The units were nineteen sixties ply, painted pink. Piles of dirty pans and crockery stood in the stainless steel sink. Mildew bloomed above the tiling. It smelt of a time before hygiene and reminded me sharply of my great-gran’s scullery with its menagerie of arthropods.

“Wait in here.”

He shut the door behind me. I could hear him go into another room and speak to someone. A women’s voice replied. They both sounded alien and upper class. My northern hackles rose. All I needed was a little hospitality. If an injured stranger turned up at my doorstep I like to think I would have behaved better. He had not invited me to take a seat, so I stood by the grimy kitchen table and waited.

The door was flung open by a young woman with long, straight brown hair. She had a craggy aristocratic face, and turned her nose up at my appearance. I apologised before I could stop myself. Seconds later she was joined by another woman, barely out of her teens, who pushed past and came up to me. She looked up at me and gave a little wriggle, like a puppy.

“Oh, how nice of you to drop in.” She came close enough for me to smell the red wine on her breath. Her right hand was bandaged. She wasn’t wearing a bra under her embroidered cotton smock.

“I”ll see to him, Annette,” the other woman said.

“We don’t have to wait for Richard anymore. We can start the party now.”

“Please, I just need to use your phone. I don’t want to . . .”

“You’re injured.”

“I had a crash. The car overturned.”

“Marcus said. You aren’t bleeding.” There was an edge of craggy sarcasm to go with her craggy face.

“I think I’ve cracked my ribs.”

“You should go to hospital.”

“Probably.”

I waited for her to go and ring for an ambulance, or offer to drive me to casualty. She and Annette looked at each other. The pause lengthened.

“So . . . if I could just use your phone?”

“You can try. It isn’t working.”

Shit. On reflection I didn’t really fancy going in a car with any of them. Annette was drunk, Marcus was stoned and the other woman, inebriated or not, was vile.

“Maybe I’d better just get myself down to the village.” I felt my legs give way even as I said it. I leant against the table and tried not to pass out.

“Oh, for god’s sake!”

“He’s going to faint.”

“Marcus! Come and help me get him onto the couch.”

Marcus drifted in. I had to put my arm round his shoulders. He was disconcertingly strong for his build. The smell of melted deodorant and stale sweat nearly made me sick. He half carried me back down the passage to their sitting room. I sank down onto a brown sofa and closed my eyes. When I opened them my vision was crowded by the three of them staring down at me. They weren’t that much younger than I was and it irritated me that they didn’t seem to have a clue what to do next. I just wanted someone to look after me. Marcus passed me a drink. I nearly shrieked from the pain in my ribs when I sat up to take the glass.

I swallowed the brandy. It did actually make me feel better. I accepted another one.

“We have no transport until Richard gets here.”

“Oh.”

“God knows what he’s going to say.”

I drained my glass.

“We could always just bump him on the head and put him in one of the out buildings,” Marcus said.

I stared at him. He laughed and came across with the brandy bottle. “Put you out of your misery.”

“Sorry to be a nuisance. . . .”

“Stop apologising. It’s so . . .” the woman gave a little shudder.

“I do like your shoes.” Annette said. She flopped down next to me with enough force to make me wince despite her diminutive size.

I was wearing trainers, blue and brown suede. She was wearing awful clumpy retro-looking platforms and flared purple jeans. I resented the sarcasm in her tone. I took revenge by drinking more of her brandy.

“You shouldn’t drink like that on an empty stomach. Do you want some supper?”

I looked at my watch. It had stopped at ten to ten. Waterproof to fifty metres, but couldn’t take a car-crash. It felt too late for supper.

“Annette! He can’t stay.”

“What are we supposed to do with him, then?”

“We could have some fun,” Marcus said. His face split into a warped smile. I wasn’t finding this amusing.

“Can I use your bathroom, please?”

“What for?” Annette asked.

The other women sighed heavily and stood up. She held her hand out to me as though I was six, and led me upstairs.

I think it was the décor that made me throw up, rather than the brandy. I puked into a lavatory bowl in two-tone maroon and pink, kneeling on a damp mat. I stayed on my knees while the pain in my ribs subsided to a reasonable level, staring at the tessellating patterns of mauve, red and brown on the walls. The splash zones of the bath and sink were tiled in mottled brown and green. No wonder the people here were so strange; they were obviously traumatised by interior design.

The craggy woman was still standing in the doorway. I groped my way to the basin and washed my face.

“Have you been here long?” I asked with as much irony in my voice as I felt her manner deserved.

She passed me a threadbare brown towel. “That’s none of your business, really, is it?”

I needed some privacy. I held the door, or rather held onto it, and waited until she got the idea and left. There was blood in my urine. I tried my phone again, but there was still no signal. I rummaged through their bathroom cabinet hoping to find some analgesics. There was only an ancient clear glass bottle of aspirin with cotton wool in the neck, obviously from the last occupant. I pocketed it in case of greater need later. It didn’t feel like stealing. I doubt it was theirs.

I pushed open the other doors before I went downstairs. They hadn’t got round to renovating the first bedroom, bare and cold and dusty in the feeble light from the landing. The other two bedrooms stank. The beds had candlewick covers in pastel shades which clashed horribly with the violent patterns on the walls. The original Victorian fireplaces had been clumsily obliterated, leaving a jagged outline visible under the paper where they had been ripped from the walls. I wondered if the Ché Guevara poster had been theirs, or if it had been left behind. Theirs, I decided. The bed was unmade in the last room, with women’s underwear lying on the floor. I remembered I was trespassing and quickly closed the door.

I heard them talking as I came downstairs.

“I doubt he’ll make it to the morning, anyway.”

“I don’t think he’s as badly hurt as he makes out.”

“I told you. Leave it for Richard.”

I paused on the bottom step. I was fairly certain that they were just talking big, fuelled by drink. Maybe they meant me to hear and be scared; that might be the “fun” Marcus had referred to. They were creepy enough, however, to make me decide to take my chances in the night.

The front door was bolted, top and bottom. I turned the Yale lock silently, then slid back the top bolt. I couldn’t bend to unfasten the bottom bolt so I cautiously began to nudge it along with the toe of my shoe. It hurt to balance on one foot, and I had to hold onto the wall for support. It was impossible to breathe quietly but they had put on some music. I relaxed a little and pushed harder. My shoe made a scraping noise. I paused, but could only hear music. The Stooges, Appetite for Destruction.

The bolt finally clunked out of its housing. I turned the door knob. The door creaked sharply.

“Going somewhere, Jonathon?”

I jumped. My ribs hurt me enough to make me cry out. Marcus was right behind me, breathing down my neck.

I opened the door wide. It was snowing heavily, with four inches on the ground. It had not been forecast, the night had been clear and cold without a cloud in the sky. I knew I was not well enough to walk anywhere through thick snow. I slumped against the wall.

Marcus reached past me and closed the door, bolting it as before.

“Go and sit down.”

The room was brighter than it had been and I was less groggy, having vomited most of the alcohol from my system. There were several table lamps and three large candles were burning on the low table in front of the sofa, amid the detritus of bottles, cigarette papers, fag-ends, mugs and glasses. Annette was standing by the fire with her back to us, swaying with the music. The other woman was now wearing glasses and holding a paperback in one hand and a cigarette in another. She looked up as Marcus escorted me in. There were more empty wine bottles than I remembered. I wondered how long I had been upstairs.

I had looked into this room once before, peering through the grimy window when I had tried to buy it. There had been no furniture, of course, as the place was empty, but I recognised the hideous wallpaper and beige tiled fireplace. Rather than redecorating, they had chosen to embrace it and furnish the house in period with their hipster lifestyle. It was almost admirable in its attention to detail. The music was coming from a large turntable in mock teak and shiny black plastic. LP covers were strewn around it on the floor. They seemed to have replicated my parents’ record collection. I wondered stupidly if Dad had sold his LPs in a car boot sale. I tried to pull my thoughts back to my current situation. I took a deep breath to steady myself, flinching with the pain.

“Sit down,” Marcus repeated.

I sat. “Look, I need some help. I’ve obviously cracked some ribs, and I think I’m concussed, or in shock, or something. Please, even painkillers would help.”

“We have wine,” the woman said, stubbing out her cigarette.

“I have some codeine left,” said Annette. She rummaged in a canvas shoulder bag and passed me a plastic tube of tablets.

I checked the label. It said codeine, but the prescription was for a Mr. R. Collins. The other woman passed me a glass of red wine. I hadn’t been able to keep the brandy down a little while ago. I looked at the wine dubiously, and swallowed just sufficient to take the pills. I put the glass down amid the clutter on the table in front of me.

The woman flopped back down in her seat and shrugged at Marcus. He began to rifle through the LPs. He selected The Velvet Underground. Sleazy music slid over me and I closed my eyes for a moment . . . Whiplash girlchild in the dark . . . I woke up with a jerk when Annette sat down astride me. I yelped and tried to push her off.

“Please. . . . . ” I could barely breathe.

“Leave him alone.”

“I”m just being friendly, Suzy. Do you have a girlfriend?”

“A wife. She’ll be worried about me.”

“What’s her name?”

“Kylie.” Even through the pain I felt a disloyal twinge of embarrassment.

“Kylie? Is that Scottish, or something?”

“Ah. Please, get off. You’re hurting me.”

She laughed. A horrible forced laugh, she knew she was hurting me.

“Please.” I appealed to the other woman. She ignored me.

A drop of blood splashed on my jumper.

“Your hand’s bleeding.”

“Does that bother you?”

It did rather but I looked at her steadily, trying to breathe as shallowly as possible. She held her hand in front of my face. It was clumsily bandaged, blood soaking through. Her little finger was missing.

“Richard did that.”

“What?”

“With bolt cutters.”

“Jesus.” I was going to be sick again. “Let me up.”

“Another bath?” She slid off me.

I tried to stand up, but ended up on my hands and knees, fighting the waves of nausea. When I looked up the other woman was standing over me holding out a glass of water.

“Try this.”

I knelt back on my heels and gulped it down. “I have to get to a doctor. She should get her hand seen to, as well.”

“Not possible, I’m afraid.”

“Why did he do it?” I asked.

She shrugged and turned away. Annette had withdrawn to the fireplace.

I closed my eyes and curled into a heap on the grimy rug, waiting for things to get better.

I must have slept. When I woke it was beginning to get light. Marcus was sprawled over an armchair and Annette was on his lap, twined round him. The room looked even more squalid in the grey dawn and it smelt like an ashtray. For a moment it seemed to shift around me, to turn into the dark dereliction that I was more familiar with. I rubbed my eyes. Suzy was stretched out on the sofa behind me. She stirred at my movement. I was so stiff I had to crawl to the door.

“Did we say you could go?” Marcus asked.

I looked around. All three of them were alert, watching me. Both women looked like clowns from some disturbing circus act, mascara smeared down their cheeks.

“I’m going to take a piss.”

“On your hands and knees?”

“If I have to.”

I scrabbled at the sitting-room door and crawled up the stairs to the bathroom. There was more blood this time. I rubbed the frost from the window pane and looked out onto a foot of snow.

I thought I had only been a couple of minutes, but as I opened the bathroom door there was already activity in the kitchen. The smell of frying bacon made me gag and salivate at the same time. I was walking almost upright by the time I got downstairs.

Annette met me at the stair-foot with a mug of tea.

“Where’s Marcus?” I asked.

“Are you scared of him?”

“No.” I lied.

“You should be.”

“How’s your hand?”

“It’s getting better. I didn’t want Richard to use my left hand. You can’t put an engagement ring next to a stump.” She held up her left hand. There was a small pearl ring on her forth finger.

“Annette,” Suzy called from beyond the kitchen door.

“What was it,” I asked, “some sort of sado-masochistic thing?”

She turned back to me, “You do say some funny things.”

“Annette. Shut up.” Suzy had come out of the kitchen and was standing in the passage. “Breakfast’s ready.”

The table was glistening in wet arcs from a dishcloth. There were four plates of bacon and eggs.

“He might as well have Richard’s.”

“Richard isn’t coming,” Annette said just as Marcus came in through the kitchen door, stamping snow off his boots. He glared at her and sat down. I sat opposite, not waiting for an invitation. We began to eat.

“I don’t think Richard is coming,” she said again.

“Be quiet. We have a guest,” Suzy warned her.

Marcus said, “It’s too late. We”ll have to see to him, anyway.”

The food turned to ashes in my mouth. There was nothing to say. I took a mouthful of tea.

“Eat up,” he said, “last breakfast for the condemned.”

“He’s taken the money and gone without us,” Annette persisted.

The grin slid from his face. He rounded on Annette, “Richard wouldn’t do that, idiot. Something’s happened. Maybe they haven’t paid. He’ll get here as soon as he can. The road’s probably blocked.”

“Or they’ve paid up, and he’s bolted.”

“Or they haven’t paid, and we’ll need another finger,” Marcus retaliated.

Annette subsided sulkily.

“Heard enough?” he asked, turning on me.

“You’ve faked her kidnap.” I focussed on the congealing streak of fat and yolk on my plate.

“Well done.”

“You’re waiting for this Richard to bring the ransom?”

“Quite advanced reasoning for a peasant.”

“So why would anyone pay a ransom for Annette if she isn’t there?”

“Obviously we said we’d deliver her after we get the money.”

I turned to Annette. “I suppose it is your parents you’re swindling?”

“I’m just getting some of my inheritance early.”

“So what makes you think they will pay a ransom for you?”

There was an uncomfortable silence for a moment.

“Richard did a lot of research,” Annette said, “we know what they can afford.”

“Being able to afford it and being willing to part with it are two different things.”

“Don’t be so damned stupid.” Marcus stood up.

The older woman looked unsure.

“They’ll be desperate to have me back.” Annette sounded aggrieved and certain.

“Sure of that? You lot are all descended from bloody cattle rustlers. The one thing all your families are good at is keeping hold of money, no matter what.” I hadn’t realised I held so much resentment until the words were out, but they didn’t seem overly offended. “What will you do if they don’t pay?”

“Give them more incentive.” Marcus stepped behind Annette, putting his hands on her shoulders. “I’m not squeamish.”

Annette blanched.

“Even if they have paid,” I continued, “sounds like this Richard has cheated you.”

Marcus lunged across the corner of the table and dragged me to my feet.

“Who asked for your opinion?” His spittle showered my face. “Take him through into the sitting room and keep him there. I need to talk to Suzy.”

Annette trotted off. I followed slowly. The room was cold. The fire had gone out. I sat down next to her on the sofa. This might be my only chance to get one of them on my own and Annette was clearly the weakest link.

“Can I have some more codeine, please?”

“I only have six left.”

“It’s time we both got out of here.”

“Why?”

“Well, for a start we both need medical treatment.”

“As soon as the ransom’s paid we’ll get over to France and I’ll see a doctor then. I think Marcus is going to kill you, though.”

“Marcus talks a load of shit. Did he force you to let Richard cut off your finger, or did he bribe you with that little ring?”

“You’re horrible. I’m not talking to you.”

“Then at least listen. How well do you know Richard?”

“Marcus knows him. They were at St. Martin’s together. I think.”

“So you don’t know him?”

“I’ve known Marcus nearly all my life.”

“Richard’s not coming, is he?”

“Marcus says he’s going to give him until midday.”

“What then?”

She shrugged but she’d lost yesterday’s perkiness. I watched her droop, cradling her hand. I waited until she had begun to snivel before I stood up. She was too busy feeling sorry for herself to bother with me. I left as quietly as I could. My legs were shaking worse than when I walked down the track to this squalid hell-hole. Marcus came up behind me and put his hand on my shoulder before I could reach out for the door knob. It seemed pointless to put up a fight until I could find myself some sort of advantage. I turned round without a word and went to sit back down next to Annette.

Marcus pulled one of the armchairs up to the coffee table and put a handgun onto the table with a decisive clunk. I stared at it stupidly for a moment and came to the depressing conclusion that he thought I was too far gone to attempt to snatch it. Or maybe he wanted me to try, to give him an excuse to finish me off. We sat in silence for a few minutes. Presently Suzy came in and sat down on the floor across the table from me. She didn’t even look at the gun.

“Well, looks like midday has come and gone,” said Marcus.

I glanced at him. It was surely not even an hour since dawn. I seemed unable to hold on to time.

“We have to decide what to do for the best.”

Annette sat next to me, making no movement to suggest she was listening to Marcus. He seemed to only be talking for Suzy’s benefit now.

Suzy glanced at Annette then turned to him, “Richard told us to stay put. He must be stuck in the snow.”

“Richard told me to cut my losses if he didn’t make it back.”

“You made plans with him, then? I thought we were all supposed to be in this together.”

“We always knew we were carrying excess baggage.”

They exchanged meaningful looks, ignoring me.

“You couldn’t!” Suzy hissed.

“We can’t take her with us. We have to cut our losses.”

“You can’t use that.”

“I wasn’t intending to. A bash on the head and put her into the stream. Death by misadventure.”

“What about him?”

“Same thing. He’s a goner anyway.”

“And me?”

“We’ll stick together, Suzy.”

The sodden lump beside me suddenly roused herself, jealousy finally penetrating where self-preservation had failed. She launched herself across the coffee table and toppled Suzy. They scrambled to their feet grabbing handfuls of hair and lashing out with their nails.

The girls I grew up with all punched and kicked as hard as the boys. I had never seen a proper cat-fight before, it’s the stuff of legend. They were lost in a frenzy of hair, blood spattering from Annette’s hand as they circled each other, locked together like Sumo wrestlers, spitting and screeching like banshees, but doing very little long-term damage.

Marcus tried to pull Annette off Suzy and one of them clawed his face. By the time he straightened up I had the gun. I threw my arm around his neck, trying to hold myself upright as much as anything, and pushed the muzzle into the side of his head. We both toppled over backwards. He landed on top of me and I pulled the trigger. His weight went slack and the girls froze in mid scuffle.

I had only ever shot rabbits before, and very few of those. I didn’t consciously consider the difference between my feeble air rifle and the heavy handgun, nor the difference between rabbits and a man. I had a gun and a target, as easy as that, as though weariness and pain were enough to absolve me from responsibility.

I heaved him off me with the dregs of adrenaline. The young women stood transfixed. I still held the gun, but I was lying back on the sofa. I would have let one of them take it from me if they had tried. The sound of a car engine outside broke into the silence. No one spoke. The car crunched to halt in the yard, buffered by the deep snow. The only person they were expecting was Richard and I had no wish to meet him.

I looked back from the sitting room door at the three of them, my victim sprawled face down, Suzy on her knees now next to his body, Annette standing behind her, staring at me through her tangled hair. Neither woman spoke. I heard someone thump on the door as I stepped into the entrance hall. I kept walking, past the stairs, down the passageway and through the freezing kitchen. I slipped out of the back door and limped round the house. The snowy courtyard was empty except for an old brown Volvo estate car, steaming in the cold. One of the women was screaming inside the house by the time I got past the car. I thought of stealing it, but the track was so steep and the snow was so deep that I doubted any of us would be driving back up that day.

I had given up trying to walk upright by the time I left the shelter belt. I crawled as far as I could up the channel that the car had made. I wasn’t aware that I had fallen flat on my face. When I opened my eyes the snow had gone, but it was bitterly cold and the sun was setting. Thankfully I had crawled further than I thought. I could see my car on the skyline above me and the road was only a few yards to my left. I hauled myself to my feet using the rough flat stones of the dry stone wall. I pulled myself to the next sheep-pole and wangled it free of its wire. It was rotten at the bottom, but strong enough to take my weight. I made it to the road, leaning heavily on the pole.

I turned to look back at Snow Fell Hall. It was getting dark but there was enough light to see the liquid movement of a big, black cat streaking up the hillside behind me. I clung to the pole and fumbled for the gun, but I had lost the dexterity to use it, I couldn’t even hold it properly, let alone raise it to take aim. I brandished the pole towards the beast, smothering the rush of air and pain from my lungs. The cat paused a few yards away, panting out a cloud of vapour in the gloaming. I took a few cautious steps down the tarmac road. It hesitated then padded after me, keeping its distance. It followed me all the way down into the valley to within the last mile to the village. The moon had risen by then and the last I saw of it, it was standing in the moonlight beside the parapet of the bridge, with its long heavy tail twitching and the glint of its eyes in the moon. I swear it was a panther.

There were houses along the road but I hobbled past the splashes of warm light from windows, unwilling to risk the kindness of strangers again. The last half mile was a long, level straight and I kept going until I reached the pub at Blanchland. The handful of drinkers jeered as I waded through thin air to the bar. The barmaid shrieked when she recognised me.

“Jonathon, good God! We’ve been out looking for you when they found your car. Where the hell’ve you been?”

I let the pole fall to the floor with a clatter and slapped the gun on the bar so that I could grab hold of the counter with both hands. The customers shuffled back. I gripped hold as tight as could, but slid down onto the stone flags anyway. I was still trying to tell them what happened when the ambulance arrived.

DI Wallace was being as patient as he could with me. I just couldn’t take it in: Snow Fell Hall was as derelict as it had ever been, no trace of habitation. I twirled the aspirin bottle between my fingers in my pocket.

“You were very lucky that you didn’t blow your hand off, firing a gun that old.”

“It was the heat of the moment. I didn’t think.”

“Well, as you can see, apart from you, there’s been no one here for a very long time.”

He was right. The house looked even more forlorn than the last time Kylie and I had trespassed to have a look round.

“I didn’t imagine it all.”

“Hallucinate, I think is what I’d call it.”

“I didn’t. It happened.”

“Something happened. You found that gun.”

It was the same gun which had been used to kill two lovers way back in the early seventies. Wallace told me the man’s name was Marcus Charlton and that he had been dead for months before a shepherd found him, rotting in the stream below the house. An unidentified woman’s body had been found a mile and a half downstream that spring after the thaw. The coroner had left an open verdict. It may not have been suicide: they may not have been lovers.

Wallace was watching me carefully as I prowled around the empty rooms.

“I”ve seen people with memory loss before. Sometimes it just comes back, sometimes it doesn’t. You can’t force it. We’ll possibly never know how you came by the gun. Whatever you shot at, we don’t have a body.”

“I shot a man.”

“You fired a gun, let’s leave it at that.”

“Whose gun was it? Humour me.”

“I can look it up. It was reported stolen months before they found Charlton’s body.”

I wracked my memory for a surname, typed on a label. “Collins, R. Collins. I think the gun may have been registered to Richard Collins.”

“The Tory candidate for Tynedale? Is it likely that he was out here last month, Mr. Hedley? Have you ever met him?” I could hear the sympathy drain from his voice.

“But the kidnap attempt?”

“We”ve been through this. No kidnaps reported. No pinkies in the post. Of course, it’s quite likely it wouldn’t be reported, particularly if it was an amateur attempt that fizzled out, but look around, there just weren’t three other people living here last week, especially not a prospective MP.”

His manner was still helpful, placating, but I could tell I had run out of favours. I hung my head and followed him out of Snow Fell Hall.

That was that. My anxiety over shooting an unarmed man in the head at point blank range was a figment of my imagination, no case to answer.

They did find evidence of the cat, however, a stinking den out in one of the sheds under a tarpaulin with recently gnawed mutton bones all around. I don’t know which was worse, being thought of as a liar, or as someone so weak-minded as to dream all this up because I’d spotted the Beast of Blanchland and had been so badly frightened I’d temporarily lost my mind. My pride hurt more than my ribs.

I tried to forget it. Kylie was kind up to a point. I recovered. I bought a bigger car and I never travelled the moors without a passenger. We took up wildlife photography. Kylie was quite good at it.

Then there was the local by-election.

Richard Collins won it. The voters here would return a Tory candidate if the Party put forward both ends of a pantomime horse. Kylie and I were walking through the park in town when we came across him being photographed in front of the bandstand.

He was in his mid sixties, the archetypal candidate. Thick grey hair, a suit which cost two grand, a flashy watch, and a self-assured smile of victory that made my flesh crawl. Richard Collins with his wife beside him.

I only recognised her because she was staring at me. But then she had aged forty years since I last saw her, and I was only six months older. We stared at each other for a moment. Then she held up her right hand, with a pearl ring on the forth finger next to the stump where the Member of Parliament for Tynedale had once cut off her little finger with bolt cutters.

“What’s the matter, Netta?” I heard him mutter, “Smile can’t you? You look like you’ve seen a ghost.”

Rowan Bowman spent her early childhood in Uganda, but has lived in the Northeast of England since the age of five. Her first novel, Checkmate, was published in 2015. She has had several short stories published, and two short stories, “The Collection” and “The Apple Tree,” won first and second prize in the Dark Times competition in 2012. Her story “Umuthi” is short-listed for the 2018 Aeon Award. Rowan has a PhD in English and Creative Writing from Northumbria University and is currently working on her second novel, On Barley Hill. Her work always has a horror element and strong narrative connections to the haunted landscapes of Northumberland. “The Beast of Blanchland” was inspired by a “big cat” sighting in the field below her vegetable garden. Within minutes of the report the hedgerows were swarming with men in corduroy carrying rifles. Rowan would like to dedicate this story to all the poor creatures, real and imaginary, who suffer from the Beasts who roam the countryside.

Rowan Bowman spent her early childhood in Uganda, but has lived in the Northeast of England since the age of five. Her first novel, Checkmate, was published in 2015. She has had several short stories published, and two short stories, “The Collection” and “The Apple Tree,” won first and second prize in the Dark Times competition in 2012. Her story “Umuthi” is short-listed for the 2018 Aeon Award. Rowan has a PhD in English and Creative Writing from Northumbria University and is currently working on her second novel, On Barley Hill. Her work always has a horror element and strong narrative connections to the haunted landscapes of Northumberland. “The Beast of Blanchland” was inspired by a “big cat” sighting in the field below her vegetable garden. Within minutes of the report the hedgerows were swarming with men in corduroy carrying rifles. Rowan would like to dedicate this story to all the poor creatures, real and imaginary, who suffer from the Beasts who roam the countryside.