HONORABLE MENTION, Summer 2020

The Ghost Story Supernatural Fiction Award

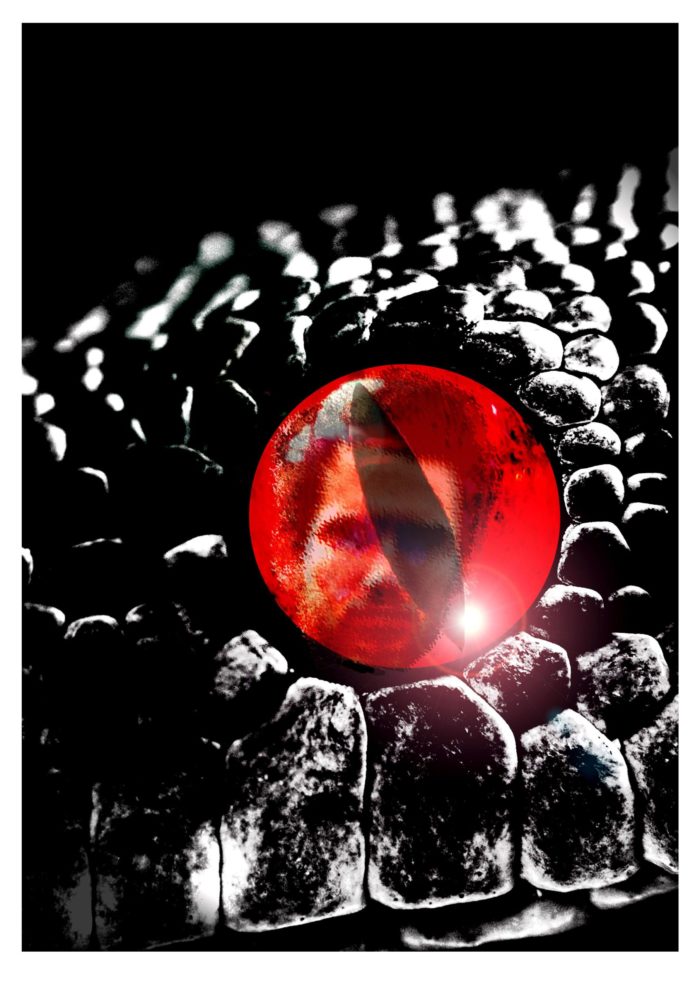

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

BY GARRET JOHNSON

And then you find a snake in your attic.

Let me back up first.

My wife and I recently moved with our two boys, both toddlers, from a narrow, three-story duplex in Montrose (an offbeat enclave of Houston’s Inner Loop) to what many would consider the burbs. I teach English at a local college. And even though my wife works in finance for one of the biggest healthcare systems in town, when our second kid arrived we just couldn’t afford it anymore. That’s the reason I give people, anyway. The real story begins—not long after our first son was born—with the rats.

Montrose was, well, is, I should say, a quirky pocket of Houston that’s both outrageously expensive and bohemian. Full of art galleries, palm readers, bearded cyclists (I was one of these myself), crumbling structures, and million-dollar homes. There’s even a guy, I swear to you, who walks the streets in a kind of wizard getup and carries a gnarled staff. I saw him once in a used bookstore instructing two teenage boys on the ins-and-outs of H. P. Lovecraft, leaning on his staff in the sci-fi aisle, running his finger across a page of The Call of Cthulhu and Other Weird Stories. I saw him another time sitting, eyes closed, deep in repose, under the giant, sprawling oak at the corner of Mulberry and Sul Ross in Menil Park. I have no idea what this man does for food, or what his relationship to those two clean-cut teens could have possibly been. I never saw him begging, never saw him working, mostly just shambling up and down the sidewalks in all four cardinal directions, the Westheimer-Montrose intersection a kind of fulcrum for his wanderings. His hair and beard are long, but he’s always well kempt, healthy looking, and he walks with purpose and dignity, like he’s thoroughly in control of his own destiny. I always admired him for this. Truth be told, I always envied him for this.

But now we really get to it. Because there’s one more thing I should say—before I tell you about the rats and the snake and all the rest of it. You see, before my wife and I had kids, I had, for some time, been nestled way down deep in the warm, cozy, soporifically iron grip of an addiction. Chemical in nature (that’s all you really need to know). But it was one of those situations where I could function pretty well at most ordinary, observable human activities, making it eminently possible to hide the fact from my wife. As soon as kid number one entered the scene, though, no dice. It was only a matter of weeks till my wife grew suspicious. I’m sure it was my bizarre, out-of-proportion responses to the smallest infractions of our sweet little bean against the ordered normalcy of pre-fatherhood life. A thin spray of pee on the wall by the changing table, for example, and I found myself clutching a lock of hair that, I numbly realized, I had actually pulled from my own head. After buckling a fresh diaper on him and transferring him to the crib with the gentleness of a mother duck trying not to crack an egg, I tore the bulky changing table from the wall, etching deep ruts into the hardwood, and sprayed down everything with Windex (do not look for rationality in this process). I then scrubbed the wall with a sponge and capped it all off by vacuuming the entire third floor. One night, that same week, a minute too long of wee-hour crying, and I leapt out of bed, stomped to the crib, bent over my son with a finger to my lips and shushed him so loudly it woke my wife (who had trained herself to sleep through the first ten minutes of his fussing). It was pitch black, but I could hear the bed creak. “What the hell’s going on?”

I just stood there hunched in the dark, shushing, finger to my lips, spittle flying, head shaking with the effort: “Shhh! Shhh! Shhh! Shhhhhhhhhhhhhhhh!” I went to the light switch and flipped it on, my wife squinting, my son bawling, and then I stalked through the rest of the house, bathing it all in what I perceived to be the cleansing light of every bulb in every room on every floor, spreading my arms to it when I was done, lifting my face to drink it all in, to smell it, this purifying brilliance.

Another time, not long after that, the banging of a rattle toy on the kitchen tile at breakfast, and I jumped out of my chair, sent it clattering, and punched a deep crack in the pantry door before marching, wordless, out of the house.

I am not proud of this.

And I had never been anything like this. It is alien and bewildering and terrifying to see yourself not yourself, or to think that, maybe, this really is your true self, and it’s just been hiding under a veneer of relative ease all this time. But in a matter of days after that pantry incident, all was laid bare—laid bare at least between my wife and me and a good therapist we’d found. Anyway, we handled it. To make a grimly protracted tale unjustly short, I kicked it. (I don’t mean to be cavalier about that part of it; it was hell; but it’s not the focus here.) And I’ve been free of it ever since. Two and half years sober, now. All should be well, especially by the point at which I’m writing this. But even back then things should have been fine—once the sobriety and the healing and the honesty started. Not easy, by any stretch. But fine. And yet, one day, not long after the first appearance of the snake, it struck me, as I stood in the kitchen browning shallots for my wife’s favorite meal, that maybe my addiction had been more complex than I’d realized.

I don’t quite know how to explain this. Except to say that I’ve come to understand one all-important thing.

My addiction is myself.

There’s a reason that H. P. Lovecraft, godfather of Cosmic Horror, wrote a story called “Rats in the Walls.” Our bedroom in that slim, tottering three-story was on the top floor, right under the attic. Well, under one of the attics—this is a crucial distinction as you’ll see in a minute. And one warm, summer night, all the world a hush, all the bad chemicals flushed clean out of my system, all three of us asleep under the broad-bladed fan sweeping its lazy circuit, my wife sprang up in bed with such a jolt it woke me, too. She sat so stiffly and so instantly upright that, even in the split second it took me to register this fact, I knew something in our home wasn’t right.

“Someone’s in our attic,” she said.

Now my wife was, and is, a very calm person. She had taken my addiction and the rocky recovery that followed (and which, she knows, is a sort of permanent fixture in our existence now) with way more equanimity than I could have hoped for. I can’t tell you how lucky that makes me, how much it helped, has continued to help, but that’s a very different story. In this moment, her voice surprised me far more by its quality than by its content. It was deeper than usual, a full octave lower. I had never heard this voice before.

My eyes were blurry, crust pinching the corners. I hadn’t heard whatever had awakened her, but I somehow knew she was telling the truth. The silhouette of her voluminous black curls emerged from the background of pale streetlight that always leaked into our room around the edges of the blinds. Her side of the bed was closer to the street. Mine was next to the closet, door always ajar. Inside the closet, in the ceiling, a thin square of plywood covered a hole that led into the attic. You needed a ladder to get up into it. On the other side of the room, beyond the foot of our bed, in a tight little nook that seemed designed just for this, our first son lay silent in his crib under a gallery wall of cartoon pictures, loving phrases in pastel cursives, and a single round mirror in a sunburst frame.

I still heard nothing.

But the lack of sound only meant our visitor had become aware of us, aware that we were awake and were ourselves aware of him. My wife’s arms were stiff out behind her, elbows locked, fists punching deep into the mattress, muscles flexed. I had never seen her so still.

After a silence so long I began to wonder if I was dreaming, a sound, as of a body being dragged across the wooden joists above our heads, scraped through room. My wife’s hand was suddenly gripping my arm, nails digging. She was pregnant with our second son at the time. And for some reason the sight of that new swell under the sheets in front of her—now that my eyes had adjusted—made the sound all the more terrifying.

This time, aside from the body itself, we also heard the footsteps of the person dragging it, as they moved from one beam to the next. A man. Perhaps. Hauling his victim by the armpits, the victim’s heels thumping along dumbly as the pair moved from one corner of the attic to the other.

“Shit,” I said.

It startled my wife and she clenched tighter. Her face. I’ve never seen one so sure of its own doom, so scared, so . . . sad. One side of her mouth dipped in that disheartening sort of frown that precedes silent tears.

Then the footsteps and the body in tow thudded and slid right over the plywood square in our closet. We both jumped and looked into the yawning black cube of space by my side of the bed. The steps above us had a shuffling element to them, like this killer or whatever he was was fatigued, or maybe just being nonchalant—which was actually the worst possibility I could think of. I struggled to imagine who could possibly be doing this. A neighbor? A vagrant? Some fugitive with excellent climbing skills or a stupid-tall ladder?

Long story short, it was rats.

Eventually, toward the end of that single, fraught hour, we figured it out. It was partly, I think, the fact that the movement was so unceasing and apparently random that I had begun to suspect even a criminal desperate or crazy enough to stash a body, noisily, in another person’s attic would have no ghost of a reason just to drag it around here and there for a whole hour.

So around 3 a.m., I grabbed the Maglite and the wooden bat I kept near my side of the bed. I moved my side table over to the closet below the cutout, stood on the table, clicked on the flashlight as quietly as I could, then slammed the wooden square up with the bat, shining my light around the attic in all directions.

I saw nothing.

But the sounds persisted.

And then I knew, and I breathed easy.

“Oh my God what?” my wife yelled.

I chuckled and climbed down. “Damn,” I said, rubbing my eyes.

So our intruders had given themselves away by their movements. The very thing that had frightened us had served eventually to reassure us.

Not so with our next intruder. Quite the opposite in fact.

The thing about snakes is that they make zero noise.

They also stay really well hidden, and you almost never suspect their presence till it’s too late. This is as true inside a home as it is out in the wild.

The night I became aware of the snake in our attic, I woke up in bed and looked over at my wife, just as I had on The Night of the Rats—as we’d come to call it.

But this time she was asleep, lying on her side, facing me, knee pillow between her legs, mouth open, rumpled sheets half off, silvery moonlight tracing the outline of her beautiful curls against the black world around her.

We had been rid of the rats for two or three months by this point and had found ourselves in a miraculous stretch of uninterrupted nights of sleep. (It’s astounding what three short months can do to an infant’s sleep preferences.) We had hired a company that specialized in sealing off residences from pests of every type and size. They were good. Amazing in fact. They had closed off every possible point of ingress (or egress), which had kept all new critters out but had also trapped a number of critters in. Our living and sleeping areas were never encroached upon, but our walls and attics were a circus of activity for a solid week. Slap traps went off about every half-hour that first day or two. And then, over time, after two straight weeks of not a single trap engaging, with the fresh peanut butter these creatures couldn’t resist left untouched and no new droppings sighted, the company declared the problem solved and told us to keep some traps set for another month, just to be sure. I left them out for good.

So we were technically sealed off, walled in, safe from all potential invaders, known or unknown. What follows should never have happened. And that, partly, is what I’m trying to come to grips with.

The moon was really bright that night. Probably full or nearly. And I hadn’t heard anything this time. I had felt something. Something had had a physical effect on me. On my skin. I felt, I don’t know, touched. As if the back of a long-fingered hand had brushed gently up the length of me, starting with my ankles and eventually, unhurriedly, reaching my forehead, leaving a trail of soft prickles behind it. It made me so cold I woke up thinking I’d kicked the sheets off in my sleep. (I hadn’t.) After turning to see my wife still asleep, I felt a second wave of those soft prickles follow the first wave’s pattern, slowly, precisely, leaving gooseflesh in its wake.

Despite the paralyzing effect of this pricking wash of cold, I felt such an acute sense of immanent harm to myself and my family that, against every natural desire, I sat up, scanned the room. And then, as if taken over by something outside myself, as if someone else had slipped into the driver’s seat of my intentionality, I shot out of bed ready to stop whomever or whatever had intruded on my home, on my family. This surprised me. I am not naturally a very brave person. Since childhood, I have woken from nightmares many times to find myself paralyzed, unable to exert my will enough even to open my eyes, look around, see if my fear has any merit. I will in these cases usually fade, over a couple of fitful hours, back into an uneasy sleep until morning finds me relieved and shaking my head at my irrationality. But this was very different. Whatever had awakened me this time had had a distinctly tangible effect on me, and it extended beyond me now to everyone else here, to my wife and our son.

Without further thought for myself, I snatched the heavy Maglite from beside my bed and strode across the room toward my son’s crib. I didn’t think, didn’t care, didn’t bother about waking him and ruining everyone’s sleep for the rest of the night. I just had to know he was okay, that he was there.

I teach English, as I’ve said, so a line from a novel came to me in that moment, a moment that extended itself out before me in a kind of mocking eternity as I stepped across the room, training the beam of a dying battery on my son’s crib, trying to decipher whether the lumps were only his blankets and those pacifiers with soft little animals attached to them, or were actually him, my son’s small body. In the half-second it took me to reach him, this line came to me—from some novel I can’t now recall—and filled me with nausea: “You do not know what it is to fear, until you have a child.”

When I finally reached his crib, I saw that it was him, the small lump near the end his head, the bigger one in the middle his bottom, raised up slightly because he always loved to sleep, when he was that age, on his stomach with his knees pulled up under him and his arms tucked in to his chest, his fists in little balls. I was hot and sick with worry, nearly to the point of vomiting. He was so still.

And a new terror struck: the thought that when I touched him I might find him cold, that the weakening beam in my hand might reveal him to be blue. Temples thumping, I reached out, put my hand flat to his back, and felt the miraculous warmth, the divine rise and fall of well-patterned breathing. Life.

I felt sledge-hammered in the back of the head with relief and literally had to sit. I slid down the wall that was just a couple feet behind me in his little crib nook, laid my head on my knees, and, I’m not ashamed at all to say, cried quietly for a good five minutes.

“Thank you,” I whispered to the dark. “God,” I said. “Thank you.” I found words tumbling out of my mouth into the silver-black night toward my son’s crib. “My dear boy,” I whispered, covering my mouth with both hands, looking up at his lopsided profile, drinking him in, “my boy, my boy.” Across the room, my wife sucked in a breath, shifted around till she was on her other side, facing the street now, and settled back into a heavy-breathing sleep.

I wiped my nose on my bare shoulder, wiped the tears away with my hands and wiped my hands on my thighs. I breathed out slowly, trying to be quiet, not to sniff.

And then I felt it again.

It started at the crown of my head this time. From there, a silken touch brushed down my back, slowly, evenly, then up the undersides of my legs, and down again to my ankles, that same wave of subtle pricks trailing after it. I was freezing again.

What is there, I thought, to my back? That question came to me. And then the answer: The other attic. The attic with a small door on the same floor as our own, down the hall and around the corner. The hobbit door, my wife and I called it. It was about three feet high, and I had to crouch half-over to get through it. Once inside, though, I could stand up fully and walk a narrow strip of space between the steep roof on one side and a wall of bare studs and exposed insulation on the other. This narrow strip went back a good 20 or 30 feet. The whole space, other than that narrow strip, was packed to the rafters: old suitcases, a spare mattress in dusty yellow plastic, boxes for computer monitors and toaster ovens, hermetically sealed containers of childhood things like stuffed animals and pillows with names stitched onto them. Again, as with the rats, I had the idea that maybe someone had snuck in with evil intent, had hidden away till the dead of night when they could emerge undetected. Again, I was wrong.

I stood from the floor by my son’s crib and turned, shined my weak beam on the inside of our bedroom door. For a moment I just stood, facing our closed door. But then I took a step. I had to. What else could I do? And so I walked, heel to toe, on the outsides of my feet, sticking close to the wall to avoid the creaky spots in the wood. When I reached the door, I turned the knob without a sound and crept out of our room, feeling that I had to see for myself, had to confront this, whatever it was, however terrifying.

Not knowing what exactly I would do, but feeling the pull of the inevitable, I crept down the hall till I reached the miniature door. I grasped the knob, turned it, held it there, and then I listened.

I heard nothing. Nothing at all. The whole city seemed asleep. But I knew I wasn’t alone. We, my family and I, were not alone.

I jerked open the door, dropped to a crouch, and shined the Maglite beam down the narrow strip where the attic was standing-height. And there was nothing. Nothing yet at least. If some intruder was in there, he was hunched low, and I knew there was only one spot where anyone could conceivably hide: at the very back, to the left, between the rafters that formed a kind of slanted wall and a big car-seat box. I stayed bent, stepped one foot through the doorway, then the other, careful to avoid the rat traps along the perimeter. I shined the beam steadily toward the back, inched forward, staying crouched even though I didn’t need to anymore. And when I got past the support beam that was flush with the car-seat box, all the way at the back, and shined the light around the corner, I stood, relaxed. There was nothing, definitely no man. Well, I thought, that’s why you check. For peace of mind. I let go the heavy breath I’d been holding and rubbed my forehead.

I turned, then, and started back toward the little door, through which I could see a bar of moonlight slanting in from the window across the hallway. Some irrational night terror, I thought. That’s all it was. But on my way back down the narrow strip, I saw, hugging the baseboard now to my left, a thick black rope glistening with the reflected light of the moon and of the pale beam in my hand. I stopped. It was a three- or- four-foot length of rope that was like none I had ever owned or had ever seen in this attic.

My feet were rooted now, but a reflex in my hand trained the beam onto this shiny black rope. One end of it rose slowly from the floor and, with a sinuous delicacy, bent itself up into a kind of S. A thin, almost imperceptible tongue flicked in and out, in that silent foray that snake tongues make into their environments, mouth closed all the while.

I bolted.

I knew, for sure, that it would strike as I went past, latch on to my calf and take me down in my own attic, that it would extend itself to a length that was much longer than I had first thought it was and would coil itself around my legs and my arms and would hold me there, till it reached my neck, where it would continue its coil and tighten itself up and flex itself around me till all was complete.

But I felt nothing. I tumbled through the small doorway and slammed the door shut behind me. My fingers searched the perimeter for cracks. But this door, leading as it did to an attic, was bordered with weather stripping and was basically airtight. I pushed and pushed to make sure the latch and strike plate had caught. And then I stood, watching it, my nearly dead beam illuminating the knob. Down the hall, behind the bedroom door, my family continued to sleep.

I never did tell my wife.

In fact I lied to her and said the rats had come back, at least one or two, and that she should stay out of that little side attic. The mere mention of rats was enough to keep her out of there, to keep her safe, for the rest of our time in that house.

I felt sure that, as long as I kept the door closed, my family would surely be fine. That I would be fine.

There was no way for the snake to get out, I reasoned, at least not into some other part of the house, maybe into a wall or something. It had gotten in somehow, but so had the rats. Maybe it had been sealed in like that last company of unfortunate rodents, and maybe this creature simply had more fortitude, more longevity, more patience and discipline than the rats who got suckered to their unwitting deaths by sweet peanut butter.

The day after I discovered the snake—you may not believe this, but I actually went back into the attic. That next morning, with birds chirping on the spindly crepe myrtle outside, and the full power of the sun shining through the same window that moonlight had beamed in through the night before, it felt totally different. I, myself, felt totally different. The fear was gone.

As I walked by the hobbit door that morning on my way to the stair head, I stopped. I looked at it, and, feeling nothing in particular, I grabbed the knob, cracked the door, and peered inside. I saw nothing, felt nothing. I closed it again and went back to our room for the Maglite, put fresh batteries in it, then came back to the hobbit door and opened it and ducked right in. I shined the light first on the spot where I’d seen the snake the night before. Nothing. I felt total freedom to walk further in, so I did. And still there was nothing.

I’m afraid, however, it wasn’t quite that simple.

As I walked back to the door, my eye went instinctively to that spot where the rope-like form had glistened in the moonlight. I got right up to it, crouched, and shined the flashlight along the floor. The decades’ worth of dust and grit that had rested undisturbed, because the edge along the wall was out of the walking path, had clearly, very recently, been troubled. I stood, feeling a dim echo in my scalp of the cold prickles I’d felt the night before, and with my flashlight I followed this disturbance in the dust back to the deepest part of the attic. All along the edge where the floor met the wall, a writhing, serpentine path wound its way through the grit. And in the very back part of the attic, I now saw a tangled mass of the same twisting pattern, full of semi-circular rubbings and long swooping arcs.

Rats, I thought at first, hoping.

But no.

First of all, the fresh peanut butter on the half-dozen slap traps I’d left out was completely untouched. Secondly, rats never made anything remotely like this kind of pattern. There was simply no way to explain this as the work of rats, or mice, or any other common pest people find in their attics—especially because the house had been sealed off by professionals, all along the rafters and the walls and at every entrance of pipe or vent or tube. An “exclusion job,” they’d called it. But, just to be sure, I called the pest company again.

I found a day when my wife was at work, my son was at daycare, and I had a couple free hours in the morning. The same two guys in faded blue Dickies who’d done the initial job showed up.

“A snake you said?” the older one asked. We were standing right outside the hobbit door.

“Yeah.”

“Seriously doubt it,” he said. “I’ve never even heard of that. Not this high up.”

“I know it sounds crazy.” I tried to laugh. “Actually, I’m hoping you can just check it out and tell me I’m off my rocker.”

He shrugged and went in. The younger man and I followed.

We all had flashlights, and when the first man got to the back, he stopped, stood, shining his bright yellow beam down on the spot. “This what you saw?” he said.

The younger man went over. He stood there for a second, seemingly unmoved, then he turned to me.

When I came around the corner at the back, I saw nothing but those swoops and arcs in the dust I’d seen that first morning. Except they seemed multiplied. The older man looked up. “That it?”

“Yeah,” I said.

He looked down at it again. “I just don’t think that’s a snake,” he said. “Probably the movers who brought your stuff in.”

“But we didn’t use movers,” I said. “And we never even come back here. These are new marks.” I don’t know why I was feeling defensive. I mean, I should have been happy. He was telling me exactly what I’d been hoping to hear. But something about the man’s casual dismissal struck a false chord with me. It seemed too unobservant. Or too hasty. How could he be so sure?

“Well someone put all this stuff here,” he said, shining his light on the car-seat box.

“Look, I’m telling you. I saw it.”

“Yeah, well.” The two men looked at each other. “I suppose anything’s possible.” The older man clicked off his light and headed for the door. The younger one followed him out, and I was right behind.

“Tell you what,” the older man said, “Why don’t we call the front office.” He shut the door behind us. “Bring an inspection team out. Check the exclusion job, maybe check for anything new. Set your mind at ease.”

“Okay, great.”

He looked at me briefly but then his eyes flicked away, as if he didn’t like what he saw. Then he started down the stairs. “You hang tight,” he said. “Our office will be in touch.” He was halfway down.

“That’s great,” I said, following. “Thank you.”

At the front door he stopped. “Good luck,” he said, shaking my hand, pulling a tight, close-lipped smile. “Give us a call if the rats come back.”

“Will do.”

And the two of them were out the door and off into the blazing Houston heat.

An inspection team did come out the following week. Cost me 85 bucks. They spent two hours checking things, on the roof, under the eaves, at every jack and pipe and exhaust vent and seam. They even went floor-to-ceiling in the attic itself. And they swore to me all was shipshape, no weak points anywhere, and no evidence of any new pests of any kind.

“But what about those tracks?” I said. “Did you look at them?”

The man in charge, some sort of supervisor, pushed up the bill of his khaki ballcap and looked at me, breathing heavily from his work. He started taking off his gloves one finger at a time. I felt, as he looked at me, for some unaccountable reason ashamed, embarrassed.

“Yeah,” he said. “I sure did.” He stuffed the gloves into a back pocket. “Don’t know what to tell you about it, but I can guarantee you there’s nothing living in there. And it’s airtight.”

I called the company again, maybe a week later, after tiptoeing in one morning and finding fresh patterns in that back area to the left.

They said they didn’t have anyone available right then, in fact not that whole week, and, come to think of it, they said, they were pretty booked the following week, too. They asked if they could call me back. I said sure. They never did. And they never returned any of my calls after that. I actually understand. Whichever way you slice it, I can’t blame them.

I have never, to this day, taken the minute or two it might require to look up whether any solid black snakes in Texas are venomous. It occurred to me once that the thing might not have even been dangerous. But in a way it doesn’t matter. The mere presence of a snake in our house, with me, with my family, even shut away in an attic where it couldn’t escape, was intolerable. I was always thinking of it, always aware, but as the weeks and months went by I realized that the last thing in the world I wanted was to go looking for it again, to actually see it. I would be downstairs in the kitchen (the room just below that attic), cooking paella with my wife, our son playing with his little Dr. Seuss Red Fish, Blue Fish toy on the floor, Spanish guitar music filling the air, safe and sugary mocktails sweating on the counter, my wife laughing at some dumb quip I’d made, telling me to taste the sofrito and see if it didn’t blow the stuff from our tapas place out of the water, and I’d take a sip from the end of a wooden spoon, and I’d find my eyes drifting to the ceiling, wondering where it was at that moment, what it was doing, what it was sensing with its sightless eyes and ever-roving tongue.

I felt, too, that it was my fault, like I had let it in somehow, like I had somehow allowed, or invited, this serpent into my family’s home and had put them all in danger—if not in mortal, immediate, physical danger, then in danger of a malign, intangible darkness that would permeate their world and be part of their lives forever.

I couldn’t stand it.

Eight months later we sold the unit. My wife had delivered our second son by that time, God love him. I know people say you should never make two major life changes at once, like having a kid and moving homes. But I couldn’t wait anymore. Not with another little one in the house. My excuse was that two tiny bedrooms, two stories apart (the ground-floor room had been my study up to then), just wouldn’t work for the four of us, not with all the months of night feedings and up-and-down comfortings and the eventual space requirements of multiple kids and a professor who needs somewhere to grade papers. My wife was all for it. I mean she was as sad as I was to leave Montrose, all the stroller walks to local coffee shops and farm-to-table restaurants in repurposed bungalows. But such cultural niceties are totally sacrificable if the altar on which they burn is designated to Sanity, and to Family—to Others.

In any case, here we are. New place. New phase of life. And I have to say, so far so good. Still sober, no blips in that department. And I find myself a part of more joy on a daily basis than I have any warrant for expecting. But I do wonder sometimes whether the new owner has had any problems. She’s a single woman who got a job at another nearby college. I’m glad it’s not mine. I’m also glad there aren’t any kids in the house. I never told her about it, obviously. I mean how do you put that on a Seller’s Disclosure? “Slithery shadow in back corner of lower attic may cause unpleasant dreams?”

But I do wonder sometimes.

I wonder whether it’s still there, a silent, dormant presence in that same shadowy corner of the same physical place. Or whether it’s moved on, maybe found a way out, or died. Or whether, look, I know this sounds irrational, but I sometimes can’t help wondering whether this sort of thing travels.

I wonder if it has the power to follow me.

I wonder if such a thing, which doesn’t travel in public and doesn’t move fast, could still somehow follow a person, from house to house, city to city, phase to phase.

I wonder this too: If the snake cannot in fact follow me, or at any rate doesn’t, will it stay put in that attic? Slithering around in some perpetual figure-eight, living off black air and dust, never making its presence known to the owner except through dim sensations, now and then, that everything in her life is not quite right, that something, somewhere, is off?

___________________________________________________________

Garret Johnson holds a Master of Fine Arts degree in fiction from the University of Houston and is an Associate Professor of English at Lone Star College in Houston, Texas, where he lives with his wife and two toddling boys. He is also co-host of the podcast A Curious Pairing—booze, books, and beauty served straight up by an English professor and his hairdresser. An earlier version of this story was a finalist for the 2019 Kurt Vonnegut Fiction Prize at the North American Review. This is Garret’s first published work of fiction. He has others, both short and long, in the works.

Garret Johnson holds a Master of Fine Arts degree in fiction from the University of Houston and is an Associate Professor of English at Lone Star College in Houston, Texas, where he lives with his wife and two toddling boys. He is also co-host of the podcast A Curious Pairing—booze, books, and beauty served straight up by an English professor and his hairdresser. An earlier version of this story was a finalist for the 2019 Kurt Vonnegut Fiction Prize at the North American Review. This is Garret’s first published work of fiction. He has others, both short and long, in the works.