WINNER, Summer 2020

The Ghost Story Supernatural Fiction Award

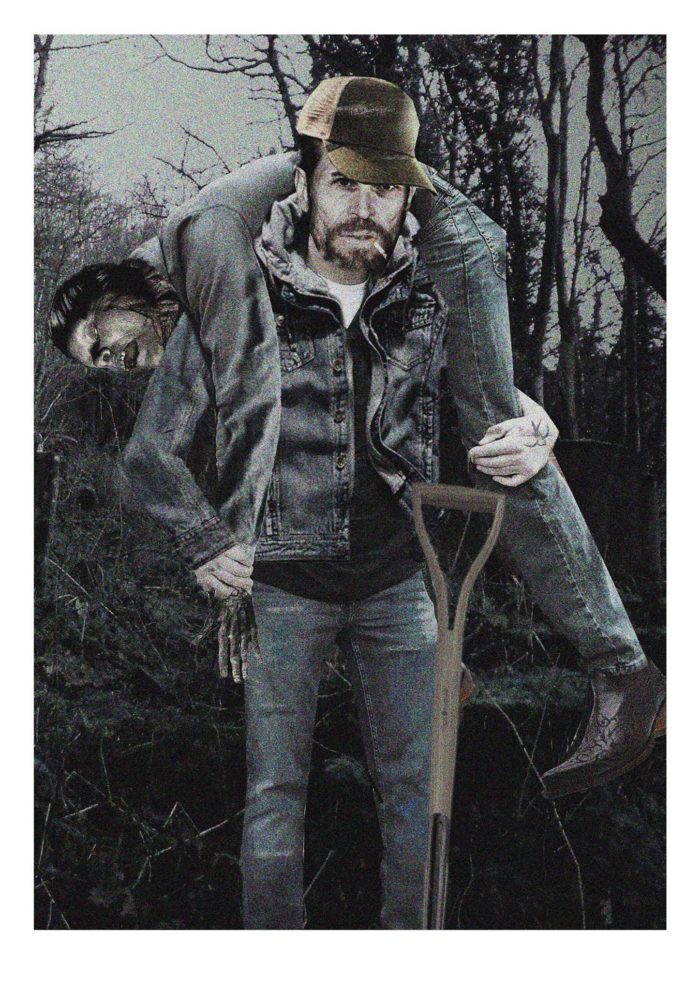

Illustration by Andy Paciorek

BY LESLEY BANNATYNE

I‘m all alone around closing time and Sid the owner is back in the kitchen loading highball glasses into the dishwasher and this corpse stumbles in and starts going on about how I gotta bury him. The juke is pumping thrash because that’s what Sid likes and it’s just me in the bar so he doesn’t care. Well it’s not just me and that’s the problem here.

“You’re none of my business,” I say to the corpse. “I don’t know you. I don’t know your people.”

“A decent person would honor a dead man’s request,” the corpse says. “A decent man would help a pal,” he says.

“You’re not my pal,” I say, eyes steady on my glass. “And I’m not a decent man.”

“You don’t have to be a decent man to do a decent thing.”

“Right.” I grab my jacket and head for the door. The corpse lets out this long spew of rot breath and starts to wail. I mean, really wail, like he’s crying for the sadness of everyone that ever lived, for the mothers that lost their babies right inside their own stomachs, for the little kids that wandered into swimming pools. I mean a deep, shin-splitting, gut-twisting kind of cry.

I take a good look at him. Skinny guy, couldn’t have been much to him even when he was alive. Feet too big for his body. Not that old, maybe 50s. Thinning black hair combed straight back and shellacked. Hands—a little pulpy.

“What’s your name?” I ask.

“Dick Doyle.” He stares down at his rumpled button-down.

“Can you walk all right?”

“No,” he says, rubbing at his eyes with a filthy sleeve.

Every instinct says leave the bar. Go home. But when a man cries, well I don’t know. What’s the harm, I think. I put on my jacket, sling the corpse’s arm over my shoulder. I know that this is not my last mistake.

Fucker still weighs about 120 pounds and I got arthritis in my shoulder from when I dislocated it when I was ten. August, me and Ray down by the Neponset River behind the power plant where the water’s always warm. Tied a fat rope to a sycamore and climbed up to swing out. But Ray pantsed me and shoved me from the tree so I flew out over the water with one arm holding onto the rope and the other holding onto my shorts. Doc eventually popped the shoulder back into place. Man that hurt, but we laughed for years about me swinging Tarzan-style over the river with my white ass hanging out. It used to make me happy to think of us all as kids—me, my little sister Patty, Ray. Now I stuff the memories as far down as I can. When they pop up, I nail them back.

“I can pay you,” the corpse says. “I’m serious. I’ll pay you. You bury me and I’ll sign over my store.”

“What store?”

“Stationery store. I’m not nobody, you know.”

I couldn’t turn it over in my head. I tried to picture the guy not as a corpse. Like a regular guy, with all his skin. Tried to imagine him in a sweater, pushing buttons on a cash register. Couldn’t do it.

My gut was telling me to leave the corpse at a shelter or church where someone would find out who he was and call all the right people. Guy’d get put in a potter’s field. Or maybe they’d make his ashes into diamonds and sell them. They do that now, turn bodies into diamonds. The carbon. Only takes a pound of ashes, says my ex-buddy Ray, and he reads The Globe every day. I wouldn’t have turned Patty into diamonds for a million bucks. Buried her right, in a nice coffin, St. Mary’s. Rose quartz stone.

“Why are you crying,” the corpse of Dick Doyle asks me.

“I’m not crying.”

“You are. Whatever you’re crying about, you should say it.”

“God, you smell like shit.” I grab him by the collar to hoist him to standing. “You sign this store over to me, I’ll get you buried.”

The corpse starts to write with a sharpie on a notecard he’s pulled out of his pocket that has a lighthouse on it. His hand is pretty shot, only tendons with a few strips of skin barely covering, like boiled chicken legs.

“What’s your name?” he mumbles.

“Thomas McGahan. How do I know you even own this store?”

“You don’t, Thomas. You have to trust me.”

He signs the deal with a sloppy mark. I put the paper in my pocket. “So, where to?” I’m getting a second wind thinking about owning property.

“I’ve always loved the graveyard behind St. Michael’s.”

Fucking corpse. That’s at least a mile away.

There is a sliver of a new moon, and the light slides like water off the leafless trees as we pass by. The corpse isn’t all that heavy now. The body gets lighter as it decays. I know this because I dated a girl who worked in a funeral home. Daphne. Gorgeous shiny black hair and a tattoo of an oilrig, never asked why. There is a difference in weight before and after a body dies, Daphne told me, but it’s not about the soul like you might think. It’s about decay; people liquefy. A soul, though—and I’ve thought about this before—a soul is an entirely separate thing; it’s more like a kite. It’s attached, but floats above. A soul is weightless. It’s clean. And if you drag it through the dirt you can send it to the karma cleaners. That’s right. Do enough good, that soul can come as clean as a Portuguese widow’s front yard. If I get this corpse buried, I can wipe some sin off my soul. And own a store.

Out of nowhere, the corpse starts singing, “Jojo was a man who thought he was a loner, but he knew it wouldn’t last.”

“Get back,” I join in. “Get back to where you once belonged!”

The gate to St. Michael’s is swung half open so I ease in and let the corpse slide to the ground.

“There’s a shovel by the shed.”

“What?”

“You have to bury me. You don’t have to dig deep, just deep enough to cover me. It’s respectful.”

It is fucking dark and the place is drowning in gloom. The shadows look like black pools choked with matted hair. Even the trees feel wrong. They’re hunched over, and when a wind comes through, their branches scratch against their own dry bark like they itch. Sure enough, there is a rusted shovel leaning against the shed. I push the shovel into the dirt, step on the blade and drive it deep. After a few shovelfuls it starts to feel good to be using my muscles. Familiar. I did this work once. Built walls. Dug up trees. Ray hauled away the crap that we couldn’t use—pieces of chain link, busted gutters. Smartest junk man I ever met. Worked the snowplow in winter. Didn’t mind the weather, ever. Ten degrees below and he’d say, this is nothing. My old man served in Korea and it was 40 below. They had to piss down the barrels of their guns to warm them up enough to shoot ‘em off. Great guy, Ray, until he wasn’t. Until he killed my little sister.

“Sonofabitch!”

My shovel hits something solid. I scrape a bit of dirt to have a look. It’s a bone. Skull, smallish, maybe a lady. Or a kid.

The corpse of Dick lets out a frustrated sigh. “Clearly, this plot is taken.”

My eyes have adjusted to the dark and I can see this graveyard is packed tight with headstones. “It looks like they all are.”

The corpse groans and tries to draw his legs up into a ball.

“Hey, hey, take it easy, Dick. I can dig in that space outside the gate.”

“No, no, no, not outside the gate. I’m not a heathen, you imbecile. I was baptized.”

I slam the shovel to the ground. It makes the wet sound you hear when a boot finds the flat of a forehead in a bar fight. Then I lie back on the grass and wonder what Dick-the-corpse did that nobody buried him. How shitty do you have to be to have no one? But I remind myself that my little sister Patty was dead, my folks were dead, and fuck Ray. So technically, I was that shitty.

“Where next?” I ask him. He’s looking pretty beat up.

“I’ve got a cousin, Maureen, buried in Dorchester North Burying Ground. We could try there?”

“Christ.”

The North is another mile down Columbia, so I throw Dickie Doyle over my good shoulder. His elbows bump against my ribcage like two boiled eggs. I get to thinking how stupid I am that I have a dead guy hanging over my shoulder and I haven’t asked him a single question. Like, how does it feel? Do you leave the earth? Can you see other dead people? And the only one I really want to know, have you seen Patty? I start thinking that this may actually be the luckiest night of my life.

“What’s dying like?”

“I’m pretty sure it’s different for everyone.”

Guy is on my last nerve. “For you, asshole.”

“Okay. It’s not as big a deal as you think it might be.”

“What’s that supposed to mean?” I stand him up against a telephone pole so we are eye-to-eye. He sighs.

“Well, all this about the last breath? It’s not all dramatic. At first, your breathing gets slower. Then, you exhale and there’s a really long time and you think, okay, this is it. But then you inhale. You can’t stop it, it happens by itself. So you exhale again, and there’s a long pause, so you drum up something to think about to pass the time. A distraction. For me it was my Ma teaching me how to shake hands properly—eye contact and a firm grip—and the next thing I knew, I hadn’t inhaled in a long while, but I didn’t care, like you don’t when you’re getting a tooth pulled with laughing gas. You feel like you should care—but you don’t.”

“And then?” Because the next part was the part I am interested in.

“What do you mean?”

“What happens next? Do you see other dead people? Do you know things you didn’t know before?”

“Yeah, you know things,” the corpse says. “You know there are no gates or clouds and you can’t see into the future of every poor fool left on earth. It’s as much a mystery to me as it is to you, Tommy.”

“Maybe you’re still in limbo.”

“Sure, that’s it. Limbo.”

“Fuck off.”

“Or maybe everyone that’s dead is still wandering around, like me. Did you ever consider that, Tommy?”

“You’re so full of shit.”

I guess it is kind of lame, imagining a nice hereafter. But it’s where I put Patty when I think of her. I don’t picture her in the ground—too cold. I think of her as smoke, lifting up and drifting along as a thin, pretty-colored smudge over the horizon. And when it rains, Patty comes down and covers all the crap we live in. I guess it’s kind of stupid. Fucking Ray.

“Who’s Ray?”

I didn’t think I was talking out loud. “The fucker who killed my sister.”

“I didn’t know you had a sister.”

“I don’t talk about her.”

The corpse looks at me to see if I’m serious. “If you don’t tell the story, Tommy, it’s like it never happened. That’s not right.”

It is nearly dawn when we get to the North Burying Ground and there’s dark clots in the sky going gray. North is a step-down from St. Michael’s. Tombstones pissed on by feral cats. Weeds. St. Pauli Girl bottles. Thank God Patty is in a better place than this. Ray wanted her cremated so he could keep her in a can but he never married her so they wouldn’t release the body to him. I got her. I was the one they called. I was the last one to see her face, so pale it was blue, to see the deep, swollen gash she got hurtling through the windshield. She wasn’t going to spend eternity in a can. And there was nothing Ray could do about it.

The North spooks me a little. I’ve heard there are really poor people buried here, people who once picked weeds and called it salad. I keep hearing a scratching sound, like claws on slate. In one corner it looks like there are the bones of a dog that wandered in and couldn’t get out.

“Look for her, would you?” Dick says. “Maureen Polaski. She was Maureen McGuinness but she married the Pole, Polaski. I can’t see so well in the dark.”

“Got it.”

The only thing that keeps me going is the way I feel when I think about owning that store. Maybe I’d sell Keno tickets. Or Powerball. Cigarettes, chips. Put in a few tables so people could spend the day. Set up a grill out back and sell hot dogs. Find a kid to waitress. Put up those little white Christmas lights. But probably, I wouldn’t.

It was becoming pretty clear to me that if you’re an asshole in life, you’re an asshole after you die, and this thought stops me cold. Patty. She did nothing but good in her life. Little Patty, gone now two years, nearly three. Pushing her on a swing when we were kids: “Higher, Tommy. Higher!”

Ray was my best friend. Only friend, really. I was happy when he and my sister hooked up—my two favorite people in the world in the same house. Yes, Ray drank. Everybody does where we come from but Ray would never admit he’d had more than he could handle. And that night—just a normal Friday night at the Eire pub—Patty told Ray right out that she was going to drive the Jeep home. She knew he couldn’t drive, he was past wasted. Couldn’t take two steps without a knee buckle. I know that’s the truth; I walked him out to the car. She got in the driver’s side of the Jeep and held tight to the wheel. But Ray was such an asshole that he kicked Patty out of her seat—literally took his boot and shoved her over to the passenger side. She looked scared. I heard her begging him to let her drive. Ray lowered himself into the driver’s seat, telling her to shut the fuck up. Hey, I said, watch it. But no one heard. Took him two tries to get his key into the ignition; first time he missed the dash and banged his knuckles on the radio dial. I heard a sudden burst of static.

Patty was staring hard out the passenger window at me, or at least it looked like she was. Ray floored the gas and scraped a trash barrel on the way out of the parking lot. I watched them tear onto Gallivan Boulevard and saw their tail lights weave across two lanes. I remember thinking I should go after them, make sure they got home all right. But I didn’t. I wanted to forget about them, get back to the bar, see if I could scrounge another drink. I didn’t do anything. And I remember thinking that Patty had really wanted them to buy that open-door Jeep because she thought it made her look cute showing her legs when she was driving.

Patty’s head went clean through the windshield and her torso was trapped inside the car, hands still holding onto her purse. Bleeding out for three hours in a ditch off the 93 on-ramp before anyone noticed the wreck. And I didn’t go after them. Can you be forgiven for something you didn’t do?

Patty in a varnished walnut box in a hole, neat edges. And all of us who loved her tossing a handful of dirt down on it. There were a lot of us who loved her. Fucking Ray survived of course. Fucking Ray who tore around that curve in the ramp, flipped the jeep, cut my little sister in two. He eventually got time for the DUI and involuntary manslaughter, but that’s no consolation for what he did. Fucking Ray stood at the edge of the grave. He kicked a little loose dirt onto the coffin with his boot. Kicked the dirt on her. People said he couldn’t bend because of the ribs he broke.

Bullshit.

Higher, Tommy, higher!

Later that night, after the burial and everyone was gone, we were both drunk, me and Ray. Ray was lying down on the front porch of him-and-Patty’s apartment. His eyes were half-open but they were dead. I sat on the bottom step, popped another beer and tried to roll the cap into the sewer grate in front of us. Cap fell short. I tried to kick it with my boot. Too far. I wanted so badly for that cap to slide down neat into the grate so I could hear the plunk of beer cap hitting the water below but that didn’t happen. I tried to forget about it.

“I told her to drive,” Ray says, pretending like he’s all heated. “She wouldn’t. Just ignored me and got in the passenger side.”

“Bullshit. I was there. You wouldn’t let her. You shoved her out of the driver’s seat, you bastard.” I got up and kicked at Ray with my boot. I missed.

“Sit the fuck down,” he snarls at me.

And I am the type of guy that does.

I don’t like to talk about Patty because it makes no sense that she’s dead. Because I didn’t say much to her the last time I saw her. And now I can’t remember things about her. I can’t remember the beginning of the joke she told about the Norwegian, can’t hear the smoke in her voice. She’s leaving me. I collapse right there in the mud of that stinking graveyard and wail for the little sister I’m forgetting. Oh Patty, oh, my little sister. Oh, love.

If you don’t tell a story it dies. So here it is, Patty’s story. She fell out of a tree down the park when she was eight and I carried her home to Ma, but then Patty pretended to have amnesia. “And who are you?” she asked, fake-mumbling on the couch. Tag sticking out from the back of her undershirt as she rode away mad on her three-wheeler. The yellow cat-face pillow she sewed in middle school, the mini-skirt she hid in the woods and changed into so Pop wouldn’t see. Patty who painted her eyelashes with watercolors when Ma wouldn’t let her wear makeup. Who stole it from Target, later. The scar on her calf where they cut out a mole, the one on her neck from climbing over eight-foot chain link on a dare. Her jewelry box with a butterfly ring and a wisp of Ma’s hair tied to it after Ma died. The baby she got rid of and never told Ray about. Her orange sweater smelling of Salem Lights that I still keep in my closet. The coffin lowered on ropes by men in baggy gray suits, a backhoe parked across on the lawn waiting for us to leave before they piled the dirt on.

There was nothing really special about Patty except there was. This is the story of Patty: she was here, and we were better because of that. Because we loved her. And now she’s gone, but we’re still better.

The first light is seeping into the shadows of the North, must be around 5 a.m. The gin has worn off and all my thinking about Patty is making me raw. I find a shovel stacked inside a shed, pick a random spot in this creepy rootscape and sink it into the dirt. I bury the shovel deeper, lever it, dump the dirt, dig again.

“Get over here,” I order Dick.

Doyle hitches himself up to the hole and slides in. Makes a few rounds like a cat, then settles. He tries to smooth out the wrinkles in his shirt but his fingers don’t work anymore, so I bend down and push each button through its hole and tuck the front of his shirt into his pants.

“I’m sorry, Thomas.” Dick’s voice is barely a whisper now. “I don’t own a store.”

“It’s okay,” I tell him. “I probably would’ve done the same thing.”

He closes his lids.

“You’ve been dead a while, haven’t you?”

“Long enough.”

“So what are you doing here?”

“Same as you, Tommy. Paying my dues.”

“And you really can’t tell me anything? You don’t know anything more than me?”

“We can’t see ahead. We can only see from above, where people pretty much look the same. We see patterns. Like sharks.”

The sun is painting the tops of the tombstones pink and the traffic’s picking up Columbia Road. I pile the rest of the dirt on the corpse, smooth out the surface, pack it down with the shovel. I pick up a few stones and set them on top. A marker wouldn’t hurt, right? I arrange some beer bottles in a circle around the mound.

I think that I should at least say something about the guy over his grave, but I realize I don’t know anything about him. I say the beginning of the Lord’s Prayer, which is all I can remember. “Our father, who art in heaven. Something about a kingdom. Get back, get back, Jojo. Amen.”

“You’re not a bad guy, Tommy,” I hear. Seems like it comes from the breeze, or leaves, or the stones themselves. Sun full up, 6 a.m., and sparrows screaming in the hedges. Think I’ll go home, get a shower, put on clean clothes, and head down to the park and see if I can find some work. I feel so good I almost feel sorry for Ray, the poor bastard.

__________________________________________________________

Lesley Bannatyne is the author of several Halloween titles including Halloween Nation: Behind the Scenes of America’s Fright Night (Pelican Publishing), which was a finalist for a Bram Stoker Award. She edited an anthology of folklore-based literature, A Halloween Reader (also published by Pelican). Her short fiction and essays have been published in Smithsonian, The Boston Globe, and The Christian Science Monitor, as well as in the literary magazines Pangyrus, Cantibrigian, Zone 3 and Shooter (UK). Her short story “Gravity” won the 2018 Bosque Fiction Prize. She lives in Somerville, Massachusetts.

Lesley Bannatyne is the author of several Halloween titles including Halloween Nation: Behind the Scenes of America’s Fright Night (Pelican Publishing), which was a finalist for a Bram Stoker Award. She edited an anthology of folklore-based literature, A Halloween Reader (also published by Pelican). Her short fiction and essays have been published in Smithsonian, The Boston Globe, and The Christian Science Monitor, as well as in the literary magazines Pangyrus, Cantibrigian, Zone 3 and Shooter (UK). Her short story “Gravity” won the 2018 Bosque Fiction Prize. She lives in Somerville, Massachusetts.